|

On the second day of the dialogue, Fonte explicitly argues that women should receive an education. She writes,

Fonte claims two things here: first, that receiving an education leads to a virtuous life and second, that in withholding education from women, men commit both an ethical and epistemic injustice. With the former claim, Fonte works to rebut the belief held by men that says an educated woman becomes immoral. She argues that, in reality, without an education, “an ignorant person is far more liable to fall into err.” Fonte defends this argument by depicting the common undesirable and uneducated women. These women, such as the “illiterate maid servants,” the “peasant girls and plebeian women,” fold to their sexual desires and easily “give in to their lovers.” Without the opportunity to exercise their minds through reading and writing, these women become “gullible” to the persuasions of men and cannot defend themselves. According to Fonte, uneducated women lack the ability to reason and as a result, must depend on the word and direction of men. Of course, even educated women are subject to the “pricking of the senses,” but their intellect allows them to combat physical temptation. For Fonte, education is just “the pursuit of virtue.” Without schooling, then, women do not have the resources to become virtuous and as a result, they inevitably give into sexual relations.

Fonte’s argument highlights the way in which men have been counterproductive and ineffective in trying to make women more virtuous. Instead of providing them with the necessary tools to defend themselves against lustful desires, men leave them weak and vulnerable. Notice that Fonte does not argue against the belief that women are naturally perverse or driven by their bodily appetites. Instead, she uses this idea as a reason in favor of giving women an education. In this way, Fonte appeals to the beliefs of men. Still, she reveals how, in the name of keeping women from their natural vices, men have inhibited women from achieving a moral life. Fonte presents the characters in her dialogue as exemplary of the benefits of educating women. It is because these women “have read [their] cautionary tales and learnt [their] moral lessons” that they “developed a love for virtue.” Readers of the dialogue, then, can look to Fonte’s characters as proof that education and virtue go hand in hand. In this passage, Fonte argues that a woman can only fight her sexual inclinations through education and that men have wrongfully repressed women who wish to pursue virtue. --MP Image info: The Education of the Virgin Mary, illustrated by Giovanni Francesco Romanelli, Italian, published in Rome in 1630. Text source: The Worth of Women: Wherein Is Clearly Revealed Their Nobility and Superiority to Men. Edited and Translated by Virginia Cox, The University of Chicago Press, 1997.

0 Comments

Here, Fonte highlights the double standard held against women with regards to their sexual relationships. While men receive praise when they have sex, women face shame from society. Relatedly, while men can boast about their sexual conquests, women are expected to hide any sign of their sexual life. Fonte argues that these responses reveal the difference in dignity between the sexes as women treat sex with more nobility than men. Yet, while men are able to find “glory and happiness” in sex, women who engage in the sex act, whether inside or outside of marriage, are necessarily degraded. It is important to note that Fonte does not argue against women feeling shame for having sex. Instead, she agrees the act is shameful but insists the shame derives from the superior sex, women, engaging with the inferior sex, men.

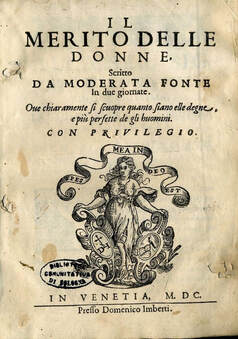

The sexes also experience a stark difference in the dependence they have on their relationships with the opposite sex. To become a “real man,” according to Fonte, one must build a relationship with a woman through marriage. Only after having that relationship can a man achieve “happiness, honor, and greatness.” In contrast, women thrive best when they are given full independence from men. Fonte emphasizes the power of female virginity as a way in which women can achieve divine greatness. A woman, untouched by men, has “something divine about her” and can accomplish “miracles.” Not only does Fonte define men as the inferior sex, she also describes them as a kind of parasite that reduces the value and abilities of women as “intercourse with men abases” women. In this way, men threaten women who seek to reach their full, sometimes divine, potential. Moreover, Fonte examines how women face greater disapproval from society in comparison to men in having sex. Cornelia, a character in the dialogue, explains the hypocrisy of this treatment, especially when it comes from men, and says, “They can keep up these curses and insults all day without once looking down at themselves and seeing that they may need to take some of the blame… if the fault is common to both sexes (as they can hardly deny), why should the blame not be as well?” (90) Once again, Fonte highlights the inequitable treatment of the sexes by society. Men encourage this unfounded response as they do not reflect on their own faults and instead, hurl insults at women who have sex despite taking equal part in the act. Throughout the first half of the dialogue, Fonte reveals the extreme hypocrisy of society in its treatment of men and women as sexual persons while also defending women as the superior sex as seen in their unique ability to thrive independently of men. -MP Text source: The Worth of Women: Wherein Is Clearly Revealed Their Nobility and Superiority to Men. Edited and Translated by Virginia Cox, The University of Chicago Press, 1997. Image info: Cover of Moderata Fonte's Il Merito Delle Donne, illustrated by Domenico Imberti, published in Venice in 1600 Source: http://badigit.comune.bologna.it/books/Moderata_Fonte/scorri.asp Modesta Pozzo, better known by her pen name, Moderata Fonte, was born in 1555 in Venice. Her parents, Marietta dal Morro and lawyer, Girolama Pozzo, belonged to an educated and wealthy class in Venice referred to as the cittadini originari. After Fonte’s parents died within the first year of her life, she was taken in by her maternal grandmother, Cecilia di Mazzi. Fonte received an education at the Santa Marta convent until the age of 9 and then continued an informal education with the help of Prosperi Saraceni, her grandmother’s second husband, and her brother, Leonardo. She was known as an extremely bright student, writing poetry of her own very early in her childhood. In her twenties, Fonte moved in with Saracena Saraceni, the daughter of Cecilia and Prosperi Saraceni, and Saracena’s husband, Giovanni Niccolò Doglioni. Doglioni, with his many connections to Venice’s literary circles, encouraged Fonte to write and helped her to publish. Much of what we know of Fonte comes from Doglioni’s Vita, a biography written on Fonte’s life published in 1600. At the late age of 27, Fonte married Filippo Di'Zorzi, a lawyer and government worker. After only a year and a half of marriage, Di'Zorzi returned Fonte’s dowry as a show of his deep admiration and appreciation of her. Fonte died in 1592, seemingly after complications with the birth of her fourth child.

By the time she was married, Fonte was well established as an exceptionally skilled poet in Venice. Throughout her lifetime, Fonte wrote various romantic and biblical sonnets, ballads, philosophical dialogues, and dramatic plays. Most famously, Fonte wrote a feminist text entitled, The Worth of Women, published after her death in 1600. The Worth of Women is a dialogue between seven Venetian women who discuss the abuse women face in light of the widely held belief that women are, by nature, inferior to men. The women discuss subjects that include the inequality in education, the abuse women endure in their marriages, and other injustices faced regularly by women in Venice. I will be looking at selected passages in The Worth of Women to explore Fonte’s philosophical analysis of gender relations and her response to the injustices faced by Venetian women. -MP Image info: Moderata Fonte (Modesta Dal Pozzo, 1555-1592). The frontispiece of Il merito delle donne. Venezia, Domenico Imberti, 1600. In Capitolo 16, Franco argues that any general weakness found in women comes from a lack of resources and opportunity and not from their nature. Franco wrote this poem as a response to Maffio Venier, a poet who publicly defamed her in his work. She writes,

Franco argues that, given proper “weapons and training,” women would have the same “hands and feet and hearts” as men. While defending the strength of women, Franco confronts an essentialist approach to the sexes. She challenges the idea that qualities like strength and delicacy are mutually exclusive and that either of them belong only to a single sex. She explains that in the same way we find tough, yet cowardly men, we can find delicate and strong women. Seeing women as weaker than men because of their general delicacy, then, fails to capture the complexity of each person as an individual. Franco sees the attack of Maffio as an attack on all women. She promises to “defend all women/ against” men like her attacker and to serve as “an example for them all to follow.” (79-80) In this role, Franco describes how she came to know her own strength. According to Franco, many women, because they lack the right training and tools, feel that they are weaker than men. She writes, “Women so far haven’t seen this is true;/ for if they’d ever resolved to do it,/ they’d have been able to fight you to death.” (70-72) Even Franco admits to feeling “defenseless” and vulnerable to the attacks of men. (22) Yet, after “devoting all [her] efforts to arms,” she came to “no longer fear harm from anyone.” (37-39) Her newfound security taught Franco “that women by nature are no less agile than men.” (34-36) In sharing her own experience, Franco argues that women can escape positions of vulnerability if they are given the same opportunities and resources as men. I think it is important to note that Franco does not ultimately challenge her attacker to a physical fight. Instead, she defends herself as an intellectual. Franco trains with the metaphorical “arms” of language in preparation for this fight. She tells Maffio that he can choose any language to battle in as she is “equally happy with them all,/ since [she has] learned them for exactly this purpose.” (126-127) She describes her attacker’s weapon as, “The sword that strikes and stabs in [his] hand—/ the common language spoken in Venice” and says that she will also fight using her rhetoric. (112-114) Towards the end of the poem she writes,

By defending herself as a skilled writer while serving as a champion of all women, she defends the intellectual capacities of her sex. Franco also highlights how her education and the chance to “practice” her craft has prepared her to win this fight. Again, she shows how the right resources can prepare a woman for any kind of combat against a man. As seen in my previous post, Franco believes that virtue is not found in bodily strength, but in the “vigor of the soul and mind.” (Capitolo 24, 61-62) Thus, in choosing to ultimately defend her superior intellect instead of focusing merely on physical strength, Franco reinforces the argument that women excel in virtue as seen in their superior reason. -MP Image info: Newlywed Venetian Bride, Noble Venetian Matron, Venetian Courtesan (engraving) Anonymous Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris. Lawner. https://venice11.umwblogs.org/venetian-attire-similarities-between-courtesans-and-aristocratic-women/#_edn

I will first look at Franco’s poem, Capitolo 24. Franco wrote this poem as a response to a man who had insulted and threatened another woman, presumably a fellow courtesan. The entire poem is 160 lines. I will examine lines 70-90 as seen below:

Earlier in the poem, Franco argues that virtue lies in the soul and mind and that women “have given/ more than one sign of being greater than men” in this way (65-66). In the excerpt above, Franco outlines the ways in which women show their superiority in virtue. Franco seems to make two arguments here: first, that submission to men serves as an act of virtue and second, that childbearing plays a significant role in both submission and in improving the condition of the world. Through their submission and childbearing, Franco argues, women are superior to men in virtue.

Franco describes the submission of women as an adaptive response to the weakness of men. Women must guide and carry men because men are weak and prone to “fall” without women’s support. Franco implies that because men “do wrong,” they cannot support the weak in the same way women support men. As a result, women must become the submissive party if they want to “avoid pursuing wrongdoing.” Submission is thus a choice women make in order to compensate for the shortcomings of men. Still, Franco reminds the man whom the poem addresses that, if women were to ignore this call to service and reveal their superiority, women would easily “surpass” men. Yet, a woman intentionally “submits to tyrannical, wicked man” and becomes “silent.” The submission of women, for Franco, acts as both a virtue and a reflection of the strength women have in comparison to men. Childbearing, for Franco, exemplifies the virtuous and indispensable submission of women. An end to the submission of women, according to Franco, directly results in an end to childbearing. Franco presents childbearing as a paradigm act of submission. Yet, in providing offspring, women have the unique ability to play a role in improving the condition of the world. For Franco, women bear children so that women do not “ruin the world” and instead, make the world “beautiful.” In this way, submission can be said to empower women as they are able to affect the world in a significant and unique manner by giving birth. For Franco, childbearing embodies the powerful sacrifice women make in order to improve the condition of the world. This submission is also voluntary and actively chosen as a result of the superior reason and morality of women. In the excerpt above, Franco tells the story of why men became the dominate sex. According to Franco, the power of men results directly from the grace and selflessness of women who are wiser and superior in virtue. In order to compensate for the failures of the weaker sex, women submit and support men. The power given to men, however, can be taken back at any time if women refuse to procreate. Yet, their virtuous and reasonable nature leads them to do what is best for the world as a whole and bring the beauty of offspring into the world. The submission of women to men, seen especially in childbearing, exemplifies the virtue and reason of women as they refrain from revealing their true superiority to better serve the world. Our first Venetian female philosopher is Veronica Franco (1546-1591), a 16th century courtesan known for her letters and poetry. Franco was born into a working class family with three brothers, all of whom received an education. Fortunately, her mother encouraged her daughter to study under a tutor alongside her brothers. It was not until after her divorce from Paolo Panizza that Franco, left with a child and the loss of her dowry, became a courtesan for highly esteemed men including Henry III and Domenico Venier. Venier, a famous poet himself and head of a renowned literary academy, provided Franco with great friendship and a space to work on her writing.

Franco’s writings critique the treatment of courtesans by the state and men. Her poetry provides insight into her personal relationships as well as her philosophical endorsement of equality between men and women. In her own defense, Franco makes herself representative of all women and argues that, given the opportunity and resources, women would have physical and mental abilities equal to that of men. Later in her life, Franco published a collection of her correspondence with her clients. Shortly after this publication, however, Franco was accused of witchcraft and her reputation was ruined. Throughout the course of her career, Veronica Franco became known for her esteemed reputation as a courtesan, her defense of equality for women, and her exceptional writing abilities. We will look at selected passages in her ‘Terze Rime’ (1575), a collection of poetry, and selected letters from her “Lettere Familiari a Diversi” (1580), a collection of 50 letters between Franco and her clients. -- MP Image : Jacopo Tintoretto (1575-1594), Portrait of a Lady. Source: Worcester Art Museum. Note: This portrait is taken to be of Franco because her name is written on the lining of the canvas During the Renaissance, Venice served as a major point of trade in Europe. With a flourishing economy, the city soon became a center for tourism, art, and culture. After adopting the printing press in the early 16th century, Venice began to produce many important works of various Greek and Roman writers. Despite the city’s freedom from the censorship of the Church, religious literature increased in production due to the Counter-Reformation in the 16th century. After the success of the Protestant Reformation, Catholic leaders fought to implement their religious doctrines in places like Venice. By 1580, there were over 60 religious households in Venice filled with thousands of clergymen, friars, monks, and nuns. Both inside and outside of these religious institutions, the production of literature backing the Counter-Reformation called for Catholic values in the home. The virtuous woman was asked to be chaste, modest, obedient, and complementary to their household and husband. As an active publication center, however, Venice also produced non-religious and anti-religious texts. Some of these works were written by Venetian women with the means to an education. They produced texts outside of and in response to the religious ideals encouraging women to serve as tokens of Catholic morality where they would be judged by their ability to perform as devout mothers and obedient wives. Over the next several months this blog will focus on four Venetian female philosophers: Veronica Franco (1546-1591), Moderata Fonte (1555-1592), Lucrezia Marinella (1571-1653), and Arcangela Tarabotti (1604-1652). By examining selected passages from their texts, we will look to highlight the nuance and significance of the feminist and philosophical insights made by these women during this time.

--MP |

Authors

Jacinta Shrimpton is a PhD student in Philosophy at the University of Sydney. She is co-producer of the ENN New Voices podcast Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed