|

In Paternal Tyranny, “Book Two,” Tarabotti argues against the belief that women are to blame for adultery. She describes this view writing,

"With artful casuistry, you spread it around that adultery is more justly condemned and punished in the wife than the husband on three counts: the damage done to the husband’s honor; the possibility of inheritance by illegitimate sons; and the threat to the safety of the husband’s life (since the adulterer supposedly kills her husband to protect his own life and allow himself greater freedom to sin). But these are not reasons; they are the ravings of evil, unbridled thoughts to allow yourself greater freedom to commit crimes without fear of reproof." (110) Tarabotti carefully responds to each claim outlined above. She begins by arguing against men who claim that women endanger the honor of their husbands when they commit adultery. Tarabotti uses the sexist reasoning of men which says that only they can bestow honor onto another to show that women, in turn, cannot hurt the honor of their husbands through adultery. She writes, “First you claim that a woman of base lineage who marries into a noble family cannot lower her husband’s status, just as a noble lady cannot raise the status of a commoner whom she marries” (111). Tarabotti argues that if a woman does not hold the power to raise or diminish the status of her husband in marriage, then, even if she commits adultery, she still cannot affect her husband’s honor. She concludes, “a woman’s dishonorable conduct… cannot bring dishonor to a house, but rather it is the man’s defects, the same man who boasts of dispensing honors to others” (111). Here, Tarabotti appeals to men’s “own weapons,” or reasoning, to defend women against unjust charges in adultery (111). Tarabotti then responds to the second claim: that women are to blame for illegitimate children and the loss of rightful inheritance. Tarabotti stresses that men are also to blame for their participation in adulterous acts. Addressing men, she writes, “for without your participation and your intrigues, illegitimate children would not be born, whose inheritances you usurp” (112). Tarabotti reframes the problem of illegitimate children as a result of men seducing women to usurp the legacy of rightful heirs. She quickly responds to the third claim, that adulterous women endanger the lives of their husbands, by referencing the story of King David and Bathsheba. In the biblical story, King David impregnates Bathsheba who is married to Uriah. Tarabotti asks her reader to “remember that it was… King David who, unknown to Bathsheba, had her husband Uriah killed” (112). She argues that King David was the direct cause of Uriah’s death, not Bathsheba who was unaware of King David’s actions. Again, Tarabotti calls her audience to recognize that women do not act alone in adultery. Finally, Tarabotti claims that the “double sexual standard” held against women in adulterous affairs opposes teachings of the Catholic church (113). She argues that “throughout the Scriptures, male and female are on equal footing when it comes to marital legislation” (113). Tarabotti references Saint Paul as an advocate of women and her views. She writes, “listen to Saint Paul agreeing with me on the reciprocal obligations between husband and wife: ‘If any brother hath a wife that believeth not, and she consent to dwell with him, let him not put her away. And if a [believing wife] hath a husband that believeth not, and he consent to dwell with her, let her not put away her husband’ (1 Cor 7:12-13)” (113). Tarabotti argues that by using the adjective “believing” to describe the wife and not the husband, Saint Paul “appreciates women’s naturally Catholic soul and sides with it” (113). Tarabotti uses Saint Paul to argue that, as seen in Catholicism, men and women should be held to the same standards in marriage. Tarabotti underlines the shared participation between men and women in adulterous acts and argues that blaming only women opposes Catholic teaching and contradicts other misogynist views held by men. Within this argument, Tarabotti showcases her ability to reconstruct opposing arguments and tactfully respond to each claim while utilizing important texts and impressive reasoning. --MP Source info: Paternal Tyranny. Edited and translated by Letizia Panizza. The University of Chicago Press, 2004. Image info: The Woman Taken in Adultery. Guercino. Italy, 1621. Source: https://artvee.com/dl/the-woman-taken-in-adultery-2/

1 Comment

On the second day of the dialogue, Fonte explicitly argues that women should receive an education. She writes,

Fonte claims two things here: first, that receiving an education leads to a virtuous life and second, that in withholding education from women, men commit both an ethical and epistemic injustice. With the former claim, Fonte works to rebut the belief held by men that says an educated woman becomes immoral. She argues that, in reality, without an education, “an ignorant person is far more liable to fall into err.” Fonte defends this argument by depicting the common undesirable and uneducated women. These women, such as the “illiterate maid servants,” the “peasant girls and plebeian women,” fold to their sexual desires and easily “give in to their lovers.” Without the opportunity to exercise their minds through reading and writing, these women become “gullible” to the persuasions of men and cannot defend themselves. According to Fonte, uneducated women lack the ability to reason and as a result, must depend on the word and direction of men. Of course, even educated women are subject to the “pricking of the senses,” but their intellect allows them to combat physical temptation. For Fonte, education is just “the pursuit of virtue.” Without schooling, then, women do not have the resources to become virtuous and as a result, they inevitably give into sexual relations.

Fonte’s argument highlights the way in which men have been counterproductive and ineffective in trying to make women more virtuous. Instead of providing them with the necessary tools to defend themselves against lustful desires, men leave them weak and vulnerable. Notice that Fonte does not argue against the belief that women are naturally perverse or driven by their bodily appetites. Instead, she uses this idea as a reason in favor of giving women an education. In this way, Fonte appeals to the beliefs of men. Still, she reveals how, in the name of keeping women from their natural vices, men have inhibited women from achieving a moral life. Fonte presents the characters in her dialogue as exemplary of the benefits of educating women. It is because these women “have read [their] cautionary tales and learnt [their] moral lessons” that they “developed a love for virtue.” Readers of the dialogue, then, can look to Fonte’s characters as proof that education and virtue go hand in hand. In this passage, Fonte argues that a woman can only fight her sexual inclinations through education and that men have wrongfully repressed women who wish to pursue virtue. --MP Image info: The Education of the Virgin Mary, illustrated by Giovanni Francesco Romanelli, Italian, published in Rome in 1630. Text source: The Worth of Women: Wherein Is Clearly Revealed Their Nobility and Superiority to Men. Edited and Translated by Virginia Cox, The University of Chicago Press, 1997.

Here, Fonte highlights the double standard held against women with regards to their sexual relationships. While men receive praise when they have sex, women face shame from society. Relatedly, while men can boast about their sexual conquests, women are expected to hide any sign of their sexual life. Fonte argues that these responses reveal the difference in dignity between the sexes as women treat sex with more nobility than men. Yet, while men are able to find “glory and happiness” in sex, women who engage in the sex act, whether inside or outside of marriage, are necessarily degraded. It is important to note that Fonte does not argue against women feeling shame for having sex. Instead, she agrees the act is shameful but insists the shame derives from the superior sex, women, engaging with the inferior sex, men.

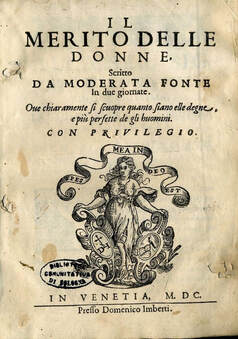

The sexes also experience a stark difference in the dependence they have on their relationships with the opposite sex. To become a “real man,” according to Fonte, one must build a relationship with a woman through marriage. Only after having that relationship can a man achieve “happiness, honor, and greatness.” In contrast, women thrive best when they are given full independence from men. Fonte emphasizes the power of female virginity as a way in which women can achieve divine greatness. A woman, untouched by men, has “something divine about her” and can accomplish “miracles.” Not only does Fonte define men as the inferior sex, she also describes them as a kind of parasite that reduces the value and abilities of women as “intercourse with men abases” women. In this way, men threaten women who seek to reach their full, sometimes divine, potential. Moreover, Fonte examines how women face greater disapproval from society in comparison to men in having sex. Cornelia, a character in the dialogue, explains the hypocrisy of this treatment, especially when it comes from men, and says, “They can keep up these curses and insults all day without once looking down at themselves and seeing that they may need to take some of the blame… if the fault is common to both sexes (as they can hardly deny), why should the blame not be as well?” (90) Once again, Fonte highlights the inequitable treatment of the sexes by society. Men encourage this unfounded response as they do not reflect on their own faults and instead, hurl insults at women who have sex despite taking equal part in the act. Throughout the first half of the dialogue, Fonte reveals the extreme hypocrisy of society in its treatment of men and women as sexual persons while also defending women as the superior sex as seen in their unique ability to thrive independently of men. -MP Text source: The Worth of Women: Wherein Is Clearly Revealed Their Nobility and Superiority to Men. Edited and Translated by Virginia Cox, The University of Chicago Press, 1997. Image info: Cover of Moderata Fonte's Il Merito Delle Donne, illustrated by Domenico Imberti, published in Venice in 1600 Source: http://badigit.comune.bologna.it/books/Moderata_Fonte/scorri.asp |

Authors

Jacinta Shrimpton is a PhD student in Philosophy at the University of Sydney. She is co-producer of the ENN New Voices podcast Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed