ENN New Voices: The Political Philosophy of Frederick Douglass: Interview with Phil Yaure10/31/2022 In this episode, Olivia speaks with Phil Yaure – assistant professor of philosophy at Virginia Tech University – about the political philosophy of Frederick Douglass. Douglass was born into slavery, but eventually became one of the most influential black abolitionists of the 19th century after escaping his enslaved condition and learning to read and write. Phil’s research focuses on Douglass as a political philosopher, with special concern for Douglass’s conception of the US constitution as an anti-slavery document and his belief that citizenship is a function of one’s contribution to a polity (in contrast to thinking of citizenship as a status that is conferred upon someone by the powers of the state). Phil argues that Douglass considers abolitionist resistance itself to be a way of contributing to American society, which leads to the conclusion that enslaved people fighting against the injustice of slavery make themselves American citizens in doing so. We also discuss the philosophical value of the autobiography genre, and Phil offers listeners some recommendations for where to begin if they want to incorporate Frederick Douglass into their history of philosophy courses.

Further Reading Autobiographies: Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (by Douglass, originally published 1845) My Bondage and My Freedom (by Douglass, originally published 1855) The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (by Douglass, originally published 1881 and revised 1892) Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (by Harriet Jacobs, originally published 1861) Select Speeches by Douglass: “The Free Negro’s Place is in America” (delivered 1851) “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” (July 5 Speech) (delivered 1852) “Claims of our Common Cause: Address of the Colored Convention held in Rochester, July 6-8, 1853” (delivered 1853) Other Sources Mentioned: Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857) Birthright Citizens, Martha S. Jones (Cambridge University Press, 2018) Immigrants and the Right to Stay, Joseph H. Carens with Deborah Chasman (MIT Press, 2018) Immigration and Democracy, Sarah Song (Oxford University Press, 2019) To listen to this episode, please visit our podcast page.

0 Comments

In this episode, Haley Brennan speaks with Dalitso Ruwe, Assistant Professor of Black Political Thought at Queen’s University, about his project of locating and understanding genealogies of Black and African philosophy. We talk about 18th century ontological and Biblical arguments against slavery, the relationship between practical and intellectual revolutions, and what it means to disrupt a system. We also discuss the value of each person’s own philosophical genealogy, and how to find philosophical content in a text. This episode is the first of a series of interviews with New Narratives Postdocs, past and present.

Select Bibliography Frederick Douglass, “Letter from Frederick Douglass to his old master: extracted from the ‘North star’." The Derrick Bell Reader, edited by Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic. James W. C. Pennington, The Fugitive Blacksmith: or, Events in the History of James W. C. Pennington, Pastor of a Presbyterian Church, New York, Formerly a Slave in the State of Maryland, United States Negro Orators and their Orations, edited by Carter G. Woodson. Lift Every Voice: African American Oratory, 1787-1901, edited by Philip S. Foner and Robert Branham. Early Negro Writing, 1760-1837, edited by Dorothy Porter. Angela Davis, Abolition Democracy: Beyond Prisons, Torture, and Empire. John Henrik Clarke, Critical Lessons in Slavery and the Slave Trade: Essential Studies and Commentaries on Slavery, in General, and the African Slave Trade, in Particular. Elizabeth McHenry, Forgotten Reader: Recovering the Lost History of African American Literary Societies To listen to this episode, please visit our podcast page. In this episode, Haley Brennan talks with Chike Jeffers, Associate Professor of Philosophy at Dalhousie University and Canada Research Chair in Africana Philosophy, about the history of Africana Philosophy. We talk about the work of, and what it is like to work on, figures including Anna Julia Cooper, W.E.B Du Bois, Edward Blyden, and Léopold Senghor. In the course of talking about these figures, we discuss the value of language to philosophy, identity, and culture, connections between the Africana tradition and current philosophical theories of race and oppression, the importance of being critical about why and how philosophical methods are appropriate for evaluating these texts, and what it means to read someone as a philosopher.

Selina Wang provided research for this episode. To listen to this episode go to our podcast page. Works Mentioned in the Episode Unless otherwise specified, all works listed are in the public domain and are available free online. Anna Julia Cooper, A Voice from the South. W.E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk. Edward Blyden, “The Origin and Purpose of African Colonization.” Chike Jeffers, “Embodying Justice in Ancient Egypt: The Tale of the Eloquent Peasant as a Classic of Political Philosophy.” British Journal for the History of Philosophy, 421-442: 2013. African-American Philosophers: 17 Conversations, edited by George Yancy. New York: Routledge: 1998. Listening to Ourselves: A Multilingual Anthology of African Philosophy, edited by Chike Jeffers. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2013. Souleymane Bachir Diagne, African Art as Philosophy: Senghor, Bashir, and the Art of Negritude (Translated by Chike Jeffers). New York: Seagull Press, 2011. Further Reading and References Chike Jeffers, “Anna Julia Cooper and the Black Gift Thesis.” History of Philosophy Quarterly, 79-97: 2016. ——, “Rights, Race, and the Beginnings of Modern African Philosophy.” In The Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Race. History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps Africana Philosophy Series: https://historyofphilosophy.net/series/africana-philosophy [Originally published on Facebook 30 April 2021]

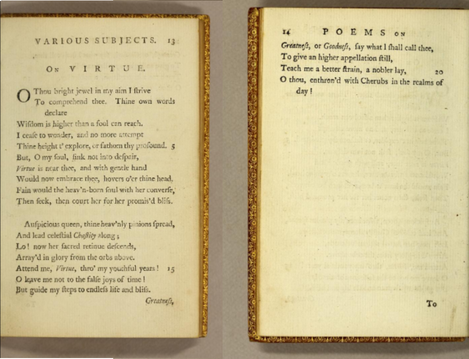

Our third and last poem is called, “On Virtue”, and it also belongs to Phillis’ poetry collection entitled, “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral” that was published in 1773. As always, a link to the digitized version is provided at the end of this post. Enjoy the poem: O thou bright jewel in my aim I strive To comprehend thee. Thine own words declare Wisdom is higher than a fool can reach. I cease to wonder, and no more attempt Thine height t’explore, or fathom thy profound. But, O my soul, sink not into despair, Virtue is near thee, and with gentle hand Would now embrace thee, hovers o’er thine head. Fain would the heaven-born soul with her converse, Then seek, then court her for her promised bliss. Auspicious queen, thine heavenly pinions spread, And lead celestial Chastity along; Lo! now her sacred retinue descends, Arrayed in glory from the orbs above. Attend me, Virtue, thro’ my youthful years! O leave me not to the false joys of time! But guide my steps to endless life and bliss. Greatness, or Goodness, say what I shall call thee, To give a higher appellation still, Teach me a better strain, a nobler lay, O Thou, enthroned with Cherubs in the realms of day! Here, it seems that Virtue and Wisdom are related, and that Virtue is a means to Wisdom. Ordinary people (the “fool”) cannot reach Wisdom because Wisdom is too high. This could make us “to cease to wonder, and no more attempt/ Thine height t’explore, or fathom thy profound”. What is left for us besides having our soul sinking “into despair”? Virtue. Virtue can not only save us from despair, but also it can serve as a guide to “endless life” and “promised bliss”. In other words, Wheatley is suggesting that Wisdom is not reached directly, but through Virtue. Thus, rather than seeking to be a wise person, she thinks we should seek to become a virtuous person first. Now, what do you make of “Teach me a better strain”? To me, Wheatley is talking about two things: what is seen and what is not. The colour of our skin is something that is seen; a virtuous soul is something that is not. It would not matter the colour of someone’s skin, for instance, but only whether that person is virtuous. Digitized Version [Internet Archive]: https://archive.org/.../poemsonvarioussu.../page/13/mode/1up -MM [Originally published on Facebook 22 April 2021]

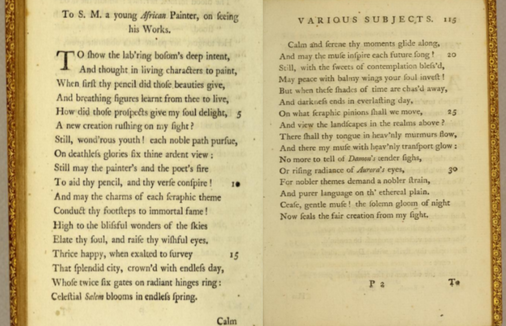

Our second poem is called, “To S.M., a Young African Painter, on Seeing His Works”. It belongs to Phillis’ poetry collection entitled, “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral” that was published in 1773. A link to the digitized version is provided at the end of this post. Here is the poem: To show the lab’ring bosom’s deep intent, And thought in living characters to paint, When first thy pencil did those beauties give, And breathing figures learnt from thee to live, How did those prospects give my soul delight, A new creation rushing on my sight? Still, wond’rous youth! each noble path pursue, On deathless glories fix thine ardent view: Still may the painter’s and the poet’s fire To aid thy pencil, and thy verse conspire! And may the charms of each seraphic theme Conduct thy footsteps to immortal fame! High to the blissful wonders of the skies Elate thy soul, and raise thy wishful eyes. Thrice happy, when exalted to survey That splendid city, crown’d with endless day, Whose twice six gates on radiant hinges ring: Celestial Salem blooms in endless spring. Calm and serene thy moments glide along, And may the muse inspire each future song! Still, with the sweets of contemplation bless’d, May peace with balmy wings your soul invest! But when these shades of time are chas’d away, And darkness ends in everlasting day, On what seraphic pinions shall we move, And view the landscapes in the realms above? There shall thy tongue in heav’nly murmurs flow, And there my muse with heav’nly transport glow: No more to tell of Damon’s tender sighs, Or rising radiance of Aurora’s eyes, For nobler themes demand a nobler strain, And purer language on th’ ethereal plain. Cease, gentle muse! the solemn gloom of night Now seals the fair creation from my sight. This poem shows us that there can be philosophical topics in poetry, topics from Philosophy of Art, or Aesthetics, including: beauty and the problem of expressing the eternal in the human realm, the aesthetical effect provoked by the author and the possibility of such an effect, timelessness or the eternal, including the nature of space in heaven. Wheatley also mentions the relationship between poetry and painting, as if both the poet and the painter conspire. Although we could continue to think broadly about such topics, it is interesting to note one particularity. Both Wheatley and the painter have something in common besides being a creator of life (a “poetes”, ποιητης). They are of the same strain. In this context, we understand “strain” as being of race, generation. By the title, this poem is to a young African painter; by the author, this poem is by an African poet. What would you think that Wheatley had in mind when she wrote this poem about an African painter in 1773? Digitized version [Internet Archive]: https://archive.org/.../poemsonvariouss.../page/114/mode/1up -MM [Originally published on Facebook April 14, 2021]

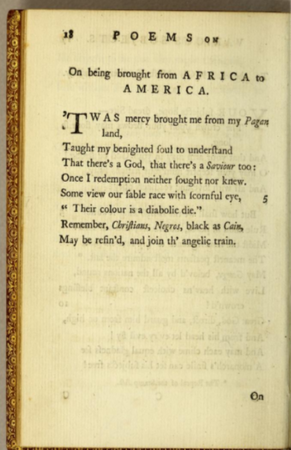

Our first poem of Phillis Wheatley is called “On Being Brought from Africa to America”, and it was published in 1773 in her poetry collection “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral”. We provide a link to the digitized version of her collection at the end of the post. Here is the poem: ‘Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land, Taught my benighted soul to understand That there’s a God, that there’s a Saviour too: Once I redemption neither sought nor knew. Some view our stable race with scornful eye, “Their colour is a diabolic die.” Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain, May be refin’d, and join th’angelic train. There are some interesting conflicts. Firstly, Phillis opens her poem saying that “ ‘twas mercy” who brought her, not slavery. Secondly, she calls her land pagan as if she ignores (we don’t know whether voluntarily or not) the sacrality of the beliefs of her homeland. The third line reinforces that idea, as if there was no God, no “saviour” in Africa, which makes us to wonder if Phillis accepted her past or not. In the fourth line, redemption was not sought by her maybe because she did not know about it. It seems that ignorance makes us away from redemption. However, that same ignorance can be found in America too because some “view our stable race with scornful eye” believing that “their colour is a diabolic die”. This apparent shift of where ignorance lies makes the end of the poem ambiguous: to whom is she talking? Who is her audience? Is she asking all Christians to remember that “Negros”, who are “black as Cain, may be refin’d, and join th’angelic train” or is she asking everyone to remember that both Christians and “Negros” could be “black as Cain”, and that both “may be refin’d, and join th’angelic train”? Finally, was this ambiguity intentional by the poet? What do you think? Digitized Version [Internet Archive]: https://archive.org/.../poemsonvarioussu.../page/18/mode/1up [Originally published on Facebook April 9, 2021]

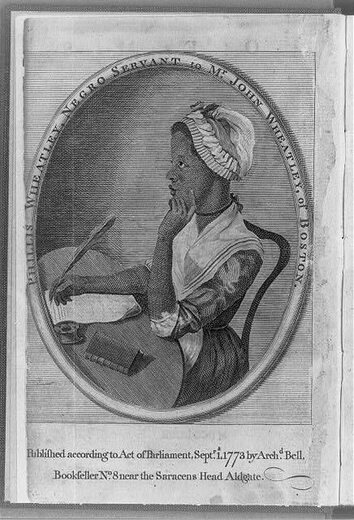

Phillis Wheatley, the first African American to publish a book of poems, is our woman philosopher of April. She was born in the Republic of Gambia, in the western part of Africa, it is thought in 1753. At the age of 8, Phillis was brought to America as a slave, when she was bought by the Wheatley family in Boston, Massachusetts. Hence, her last name. Her first name is due to the ship that brought her, the Phillis. The Wheatley family taught her Astronomy, Geography, Literature, English, Ancient Greek and Latin. After 16 months, Phillis could read the Bible, Greek and Latin classics (in Greek and in Latin), and British Literature. In 1767, Phillis published her first poem, “On Messieurs Hussey and Coffin”. In 1770, she published “An Elegiac Poem, on the Death of the Celebrated Divine, and Eminent Servant of Jesus Christ, the Reverend and Learned George Whitefield”, which brought her notoriety. In 1773, she went to London to publish her collection of poems called “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral”. There, Phillis met people such as Baron George Lyttleton, Sir Brook Watson, John Thorton, and Benjamin Franklin. The travel was sponsored by the English Countess of Huntington, Selina Hastings. Her book is considered a landmark achievement in the US history. Due to the unusual fact that the book was written by a slave, her book included a preface with 17 Boston notable men attesting that it was indeed written by Phillis, a slave. John Hancock, who signed the United States Declaration of Independence, was among those men. Phillis was emancipated after the book’s publication. Defender of freedom and liberty, Phillis wrote poems supporting America’s fight for independence. Let me mention here the poem called “His Excellency General Washington”, which was sent by Phillis directly to Gen. George Washington in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1775. One year later, Washington invited Phillis to visit him. She accepted. Other themes in her poems include: religious rites, death, and slavery. She died on December 5, 1784, due to complications from childbirth. It is believed that she wrote 145 poems. Her work contributed to American literature, and her literary and artistic talents helped to demonstrate that African Americans were equally capable, creative, intelligent human beings who benefited from an education, helping the cause of the abolition movement. If you want to know more about her, take a look at these websites: National Women's History Museum (US): https://www.womenshistory.org/.../biogra.../phillis-wheatley Biography: https://www.biography.com/writer/phillis-wheatley Poetry Foundation: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/phillis-wheatley -MM [Originally published on Facebook 24 February 2021]

Our last post about Mary Ann Shadd Cary is about a sermon. We know little about this sermon, only that it was delivered to an audience in Chatham, Ontario, in 1858. The more we read it, the more complex it becomes. What is it about? Naturally, there is an abolitionist theme. However, how to understand sentences such as “The spirit of true philanthropy knows no sex” or “She (woman) too is a neighbour”? Here is one of the intro paragraphs. “These two great commandments [to love the Lord our God with heart and soul, and our neighbour as our self], and upon which rest all the Law and the prophets, cannot be narrowed down to suit us but we must go up and conform to them. They proscribe neither nation nor sex – our neighbour may be either the oriental heathen, the degraded Europe and or the enslaved colored American. Neither must we prefer sex the slave-mother as well as the slave-father”. This sermon is about more than just the colour of our skin. To me, it’s about love. Love that is both to “the Lord our God”, to “our neighbour”, and to ourselves too. Love “upon which rest all the Law and the prophets”, and that “cannot be narrowed down to suit us”, but that “we must go up and conform to” it. Further in the sermon, Mary Ann Shadd Cary says that we should “waive all prejudices of education, birth, nation or training” to practice that kind of love. That illustrates that she is not talking about sexual or bodily love; she is talking about transcendental love. A love that goes beyond our attributes such as color or sex, for instance. The word “neighbor” could mean everyone. Someone who has a different religious belief than us (“the oriental heathen”), someone whom we don’t respect (“the degraded Europe”), or someone who has been deprived of what we may take for granted (“the enslaved colored American”). But, if we have to consider everyone as our “neighbours” and we have to love them as we would like to be loved, then what would happen to slavery or to inequality? In the end of her sermon, Mary Ann Shadd Cary says that we’re all equal because we share a “common origin”, and were it not for “the monster slavery, we would have a common destiny here.” The meaning of “here” is open to interpretation, but I think she is not limiting her sermon to Chatham, Ontario, April 6th 1858. That is why we’re still talking about her in 2021. --MM [Originally published on Facebook on 17 February 2021]

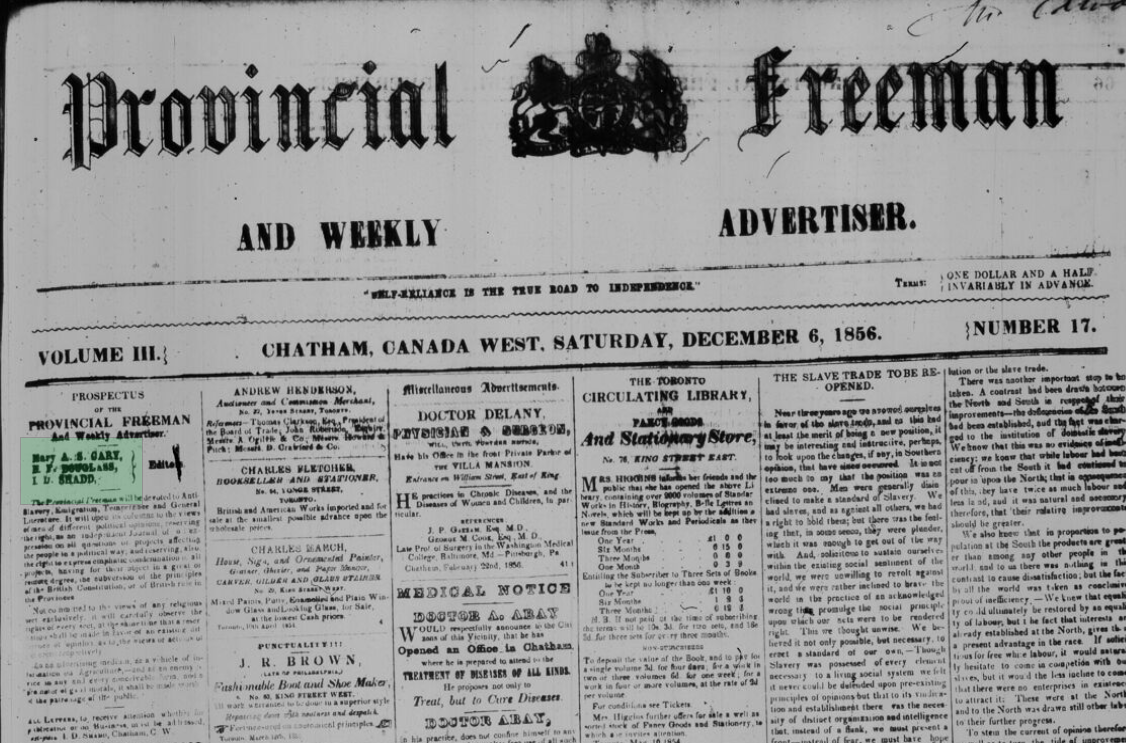

Last week, we talked about Mary Shadd Cary’s A Plea for Emigration. Today, I bring her editorial about the United States presidential election in 1856. Here is a passage: “Instead of a handful of abolitionists, from motives of humanity, the world beholds millions of abolitionists from necessity, and depend upon it there will be hard and bloody work, before the struggle terminate[s]! We heartly deplore the prospect. There is no one so thoroughly depraved! as to love violence for its own sake, but the oppressor of the colored man has forced the necessity” Her words are provocative, aren't they? There will be “hard and bloody” work. Violence will happen whether one protests against slavery or not. The election result shows that slavery is not going to be solved through politics. There is a moral difference among people. It is not a matter of opinion or of facts, it is a matter of moral principles. On one hand, some people believe that slavery is morally acceptable; on the other hand, some do not. Those who do not happen to be oppressed by the former. How to solve that when you do not have rights to protect you and the only people who can recognize those rights into laws are against you? In such scenario, Mary Shadd Cary says that you do not solve this problem without “hard and bloody work”. Violence for its own sake is not morally justifiable, but if all forms of peaceful resolutions are doom to fail, violence as a mean to a greater good may be. It is interesting and cool to see that Philosophy can be found in a newspaper editorial. Next week, we will see that it can be found in a sermon. For historical background: in 1856, James Buchanan was elected the 15th president of the United States. Mary Shadd Cary’s editorial was written two weeks after the election result. She said that “A fearful thing is the result of that last presidential election!”. For her, United States politics was not about being Republican or Democrat; it was about being abolitionist or pro-slavery. Since 1854, the growing apathy towards slaved people, the persecution of abolitionists, and the inefficacy of debates on whether or not slavery was morally acceptable had caused violent riots such as the one known as “Bleeding Kansas”. Mary Shadd Cary’s editorial was predicting that things were going to get worse. Five years after Mr. Buchanan’s election, the United States entered in civil war. --MM Picture retrieved from Canadiana - by Canadian Research Knowledge Network (CRKN) – for research use: [Originally posted to Facebook 11 February 2021]

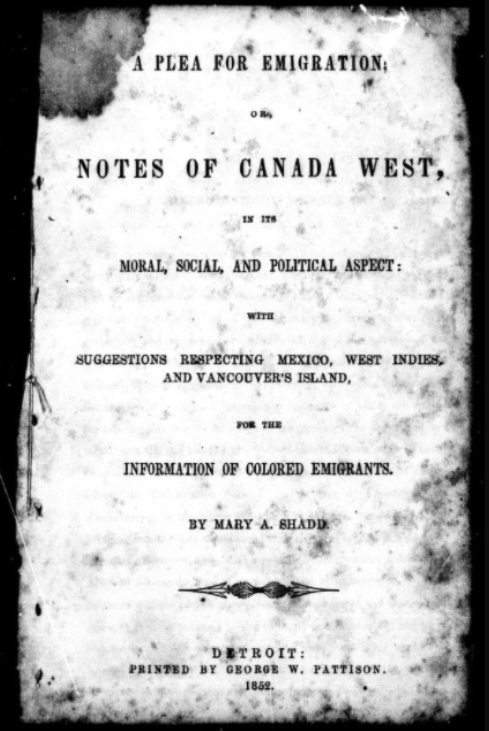

Today I’m going to talk about A Plea for Emigration, the first book published by Mary Shadd Cary. After the Second Fugitive Slave act was passed, life in the United States became even more dangerous. People were looking for a better place to live and Canada was one of those places. Noting the “absence of condensed information accessible to all”, Mary Shadd writes A Plea for Emigration in 1852. As the title suggests, the book not only informs, but pleads. Go to Canada. There the summers are short, people speak mostly French, and there are as many beautiful rivers and streams as apples. However, that seems to be beside the point. There is a passage that I want to highlight. “Lands out of the United States, on this continent, should have no local value, if the questions of personal freedom and political rights were left out of the subject, but as they are paramount, too much may not be said on this point. I mean to be understood, that a description of land in Mexico would probably be as desirable as lands in Canada, if the idea were simply to get lands and settle thereof; but it is important to know if by this investigation we only agitate, and leave the public mind in an unsettled state, or if a permanent nationality is included in the prospects of becoming purchasers and settlers”. The point seems to be that personal freedom and political rights are paramount. But what does she mean by that? To have the possibility to not only buy a land, but also to be a settler. To belong to a community, to have a permanent nationality. Maybe to vote and being a voter, to have rights or titles, to belong in a State. To be respected, protected and allowed to pursue a life with dignity. It is not just about whether the land itself is fertile or not. If it were, there would be no difference between Canada, Mexico or the United States. All lands could be fertile, but not all lands are equal. Picture retrieved from Internet Archive for research use only: https://archive.org/details/cihm_47542/page/n5/mode/2up -MM |

Authors

Jacinta Shrimpton is a PhD student in Philosophy at the University of Sydney. She is co-producer of the ENN New Voices podcast Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed