I was immediately drawn to Veronica Franco after learning she was not only a feminist and poet, but also a sexworker. Franco’s writing is proudly erotic and boldly explicit as she describes her life as a courtesan. To me, Franco’s unapologetic confidence in her sexuality exemplifies an aspect of womanhood that even today sometimes feels taboo.

Moderata Fonte’s writing, on the other hand, felt more familiar to me. Fonte presents her philosophy through a dialogue held between women. Although familiar in style, Fonte is exceptional in her character development. While reading, I could feel the camaraderie between the women as they joked about things like the inevitable imprisonment of marriage with a soon-to-be bride. I was moved by the sense of community these women provided each other with (although this serves only as the backdrop to Fonte’s excellent feminism and natural philosophy). While many philosophers appeal to the dialogue form, few create such impressive and dynamic characters who can put forth important ideas in a way that does not feel forced or stiff. Perhaps in a manner less graceful than her predecessors, Lucrezia Marinella also presents strong feminist arguments. Aside from her philosophy, Marinella’s descriptions of men like Aristotle are simply fun to read. Zeroing in on the defects of his work many times throughout her text, Marinella describes Aristotle as “foolish…cruel…a fearful, tyrannical man, and sarcastically, as “our good friend Aristotle.” Marinella is ruthless in her analysis of the works of men like Aristotle, making her overall text a page-turner (an accomplishment which sometimes feels like a rarity in philosophical writing). Unknowingly saving the best for last, I finished my research with Arcangela Tarabotti. In Paternal Tyranny, Tarabotti is explicit in her call for an end to the practice of men forcing women who do not have religious vocations into convents. Tarabotti directs her work at men, bringing them into the dialogue by continuously addressing “you”. Without hesitation, Tarabotti puts these men on trial: “Your lying insulting tongues never cease… You cruel hypocrites… You bloodthirsty butchers… You liars!” Throughout her work, Tarabotti’s anger and hurt is palpable. By the end of the text, I could feel the desperation in her voice as she begged for the most basic form of empathy from the most apathetic oppressors. On a personal note, there is something deeply familiar about Tarabotti’s anger. To me, she seemed most frustrated by the hypocrisy of men who call themselves Christians but fail to uphold Christian values. Of course, this kind of experience of religious groups is not isolated to Tarabotti or 17th century Venice. And so, her frustration seems timeless, and, in many ways, she took the words right out of my mouth. Overall, in reading the texts of these women, I enjoyed engaging with various styles of rhetoric, all of which are strong in personality and conviction. Their work serves as a reminder of the importance of the presence of the perspective and ideas of the oppressed in philosophical discussions.

0 Comments

Despite her many critiques of Aristotle, Marinella utilizes Aristotle’s concept of material and efficient causes in her defense of women. She writes,

Marinella argues that each creature shares an efficient cause in the one “Eternal Maker” or God. Despite sharing this “productive cause,” however, the creatures of the world vary in degree of perfection. Marinella claims that the degree of a creature’s perfection mirrors the perfection of the Idea or Form of that creature. Here, again, Marinella appeals to the Platonist Forms. She quotes Petrarch, who, while speaking about his beloved, Laura, writes, “In what part of the world, in what Ideas was the pattern from which nature copied that lovely face, in which she has shown down here all that she is capable of doing up there?” (54) Marinella uses Petrarch, a fellow Platonist, to highlight how the beauty and perfection of women can be traced back to the “pattern” or Idea of women in God.

Marinella describes God’s “divine precognition” of Ideas writing, “To give you a clearer example of this sort of Idea, let us pretend that an artist wishes to paint a beautiful Venus… There is no doubt that before the artist begins to draw or paint he will have fixed in his mind the sort of figure he wishes to paint and only then will he proceed to bring this image to life” (53). Like the painter, God imagines the Idea of each creature before He creates them. God also determines the degree of perfection for these creatures as He “decides which things are of less value and which are worthier”. According to Marinella, God’s “Idea of women is nobler than that of men” as seen in their unmatched “beauty and goodness” (53). In making women more perfect in Form, then, God reveals that women are worthier creatures than men. Marinella swiftly argues at the end of the chapter that women are also more excellent than men in their material cause. She writes, “I do not need to make an effort over this since, as woman was made from man’s rib, and man was made from mud or mire, she will certainly prove more excellent than man, as a rib is undoubtedly nobler than mud” (54). Marinella positions her argument within the context of the story of creation. As Eve is made from Adam’s rib and Adam made from mud, Eve, who represents all women, has a superior material cause in comparison to Adam, who represents all men. Here, once again, Marinella carefully works Aristotle’s philosophy into her defense of women as she concludes that, in both their material and efficient causes, women are superior to men. In doing so, Marinella shows her ability to critique thinkers like Aristotle while appreciating, understanding, and employing other aspects of their philosophy within a feminist defense. --MP Text source: The Nobility and Excellence of Women, and the Defects and Vices of Men. Edited and translated by Anne Dunhill, The University of Chicago Press, 1999. Image info: The Virgin Reading. Painted by Vittorio Carpaccio. Published in Venice, 1505-1510. Source: https://www.wga.hu/frames-e.html?/html/c/carpacci/2/08virgin.html  It is hard to ignore the amusing and explicit contempt employed by Marinella in her prose as she criticizes various male thinkers. Throughout The Nobility and Excellence of Women and the Defects and Vices of Men, Marinella often critiques Aristotle and his claim that women are, by nature, the inferior sex. In rebutting Aristotle, Marinella defends her natural philosophy and advocates for equal opportunity among the sexes. She writes, "But in our times there are few women who apply themselves to study or the military arts, since men, fearing to lose their authority and become women’s servants, often forbid them even to learn to read or write. Our good friend Aristotle states that women must obey men everywhere and in everything and not such for anything that takes them outside their houses. A foolish opinion and cruel, pedantic sentence from a fearful, tyrannical man. But we must excuse him, because, being a man, it is only natural he should desire the greatness and superiority of men and not of women. Plato, however, who was truly great and just, was far from imposing a forced and violent authority. He both desired and ordered women to practice the military arts, ride, wrestle and in short, to instruct themselves in the needs of the Republic… If [women] do not show their skills, it is because men do not allow them to practice them, since they are driven by obstinate ignorance, which persuades them that women are not capable of learning the things they do." (79-80) Marinella argues that, in order to maintain their authority, men do not allow women to receive an education or to practice the military arts. Out of fear, these men repress those, mainly women, who hold the potential to threaten their power. For Marinella, Aristotle serves as a prominent example of this “tyrannical man.” Marinella pits Aristotle against Plato “who was truly great and just.” Unlike Aristotle, according to Marinella, Plato rightly advocates for the training of women in various practices dominated by men such as riding, wrestling, and military arts. Any absence of skill or ability found among women in these fields results only from the lack of education and opportunities available to women. Marinella describes the circular nature of this phenomena as a self-fulfilling prophecy where men keep women from being educated and then become convinced that women cannot learn. According to Marinella, Aristotle’s endorsement of limiting women to household work and excluding them from schooling exposes the ignorance and injustices in his philosophy. Marinella also argues that Aristotle’s natural philosophy, which he uses to defend his anti-women views, fails upon further consideration. Both Marinella and Aristotle hold that a person’s bodily temperature says something about their character or nature. According to Marinella, however, Aristotle argues that men are hotter than women and therefore, more noble. She writes, “The good Aristotle, state[s] that women are less hot than men and therefore more imperfect and less noble. Oh what irrefutable and powerful reasoning! I now believe that Aristotle did not consider the workings of heat with a mature mind, nor what it signifies to be more or less hot, nor what good and bad effects derive from this” (130). Unlike Aristotle, Marinella argues that only moderate heat reflects a noble soul. “Excessive heat,” like that of men, “makes souls precipitous and unbridled” while “little and failing heat…is powerless for the soul’s operations” (130). Marinella declares that “women are cooler than men and thus nobler, and that if a man performs excellent deeds it is because his nature is similar to a woman’s, possessing temperate but not excessive heat” (131). As a defense of women as the superior sex, Marinella argues that Aristotle misunderstands the relationship between temperature and soul as the excessive heat of an individual exposes only the defects of their soul. If men are hotter than women as, according to Marinella, Aristotle believes they are, then they are inferior to women by nature. Not only does Marinella attack Aristotle’s misogyny in advocating for inequal opportunity among the sexes, she also highlights the failures of his natural philosophy in his attacks on the nature and temperature of women. Although decorated with colorful insults and bold sarcasm, Marinella’s arguments against Aristotle clearly reveal her expansive knowledge of thinkers like Plato and her own extensive natural philosophy. -MP Text source: The Nobility and Excellence of Women, and the Defects and Vices of Men. Edited and translated by Anne Dunhill, The University of Chicago Press, 1999.

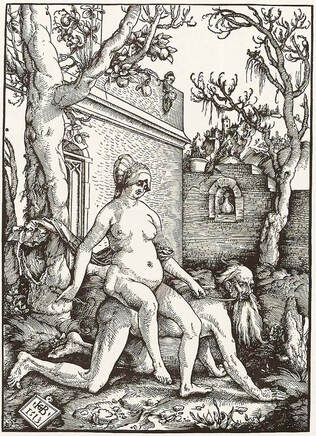

First image info: Image taken from Maria Bandini Buti, Enciclopedia biografica e bibliografica italiana: poetesse e scrittrici (Roma, 1942), vol. 2, p. 10. Source: https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/efts/IWW/Portraits/HTML/A0190.html Second image info: Aristotle and his lover Phyllis. Hans Baldung Grien, 1515. http://www.ibiblio.org/wm/paint/auth/baldung/ In reading chapter III of The Nobility and Excellence of Women and the Defects and Vices of Men, I am most interested in Marinella’s appeal to the philosophies of Aristotle and Plato in establishing her bold feminism. Marinella argues that the natural beauty of women reveals the divine excellence of their souls. She writes:  So if women are more beautiful than men, who, as can be seen, are generally coarse and ill-formed, who can deny that they are more remarkable? Nobody, in my opinion. Thus it can be said that beauty in a woman is a marvelous spectacle and a miracle worthy of respect, though it is never fully honored and respected by men. But I wish to go further and show that men are obliged and forced to love women, and that women are not obliged to love them back, except merely from courtesy. I also wish to demonstrate that the beauty of women is the way by which men, who are moderate creatures, are able to raise themselves to the knowledge and contemplation of the divine essence. (62) Marinella first argues that women’s being naturally more beautiful than men reveals the superiority of their souls. She writes, “The greater nobility and worthiness of a woman’s body is shown by its delicacy, its complexion, and its temperate nature, as well as by its beauty, which is a grace or splendor proceeding from the soul as well as from the body” (57). In order to argue that one’s bodily appearance mirrors the state of one’s soul, Marinella appeals to the idea of the hylomorphism found in Aristotle where the soul is the form of the body and body is the matter of the soul. She asks, “What is the form of the body if not the soul? The greatest poets teach us clearly that the soul shines out of the body as the rays of sun shine through transparent glass” (57). The soul, acting as the form of the body, serves as a template for the appearance of the body and, in its bodily existence, reveals the true nature of the being. The more beautiful a woman’s body is, then, according to Marinella, the more beautiful her soul will be. In comparison to women, however, “all men are ugly” and therefore, inferior in their souls (63). With Platonism in mind, Marinella argues that the origin and cause of the external beauty of women is God. God uses the forms, such as beauty, to fashion the external world in the most perfect way. Marinella describes God as “the minister who takes [beauty] … from every other source of perfection and excellence” in order “to create this rich and esteemed treasure house of beauty” (62). Corporeal beauty, then, is personally bestowed by God onto only the worthy creatures of the world (59). Great beauty, like that seen in the bodies of women, reveals a divine nobility and excellence in the being. She writes, “Each writer, Platonist, and poet affirms that beauty comes from God… Divine beauty is, therefore, the first and principal cause of women’s beauty, after which come the stars, heavens, nature, love, and the elements” (60). Like other beauties in the external world, the beauty of women stems from God. Men, however, do not have this beauty. This disparity, according to Marinella, shows that men are less worthy beings than women who are chosen to embody a divine form such as beauty. Most interestingly, Marinella concludes that if women are more beautiful than men, and if this beauty originates in God, then men are obligated to love and contemplate the beauty of women because it will lead them to knowledge of God. She asks, “What poet is there, however coarse, who does not state openly that beauty is the path that guides us directly to the contemplation of divine wisdom…beauty, not being earthly but divine and celestial, always raises us toward God, from whom it is derived” (66). Marinella’s argument here positions women as invaluable gateways to God and beauty itself. In this way, women, by their very nature, demand worship and love while men do not. Nodding to Homer, Marinella describes this phenomena as a “golden chain” (66). Similar to Diotima’s Ladder of Love, found in Plato’s Symposium, Marinella describes our love for physical beauty as a way of ascension to higher forms of beauty. First, we see “corporeal beauty” which is “gazed at and considered by the mind, through the means of the outer eye” (66). In admiration of this beauty, we “ascend” and look “with the internal eye at the soul that, adorned with celestial excellence, gives form to the beautiful body” (66). In contemplation of the soul, we consider the “angelic spirits” and “this contemplative mind seats itself within great light… of the one who supports the chain” (66). In appreciating corporeal beauty, we are led to “delight in Him” and are “made happy and blessed” (66). Men, then are obligated to contemplate the beauty of women because they will be naturally led to a contemplation of the divine. Marinella defends the superiority of women with an appeal to Aristotle’s hylomorphism, Plato’s forms, and by arguing that their bodily beauty reflects their beautiful souls which lead men to knowledge of God. --MP Text source: The Nobility and Excellence of Women, and the Defects and Vices of Men. Edited and translated by Anne Dunhill, The University of Chicago Press, 1999.

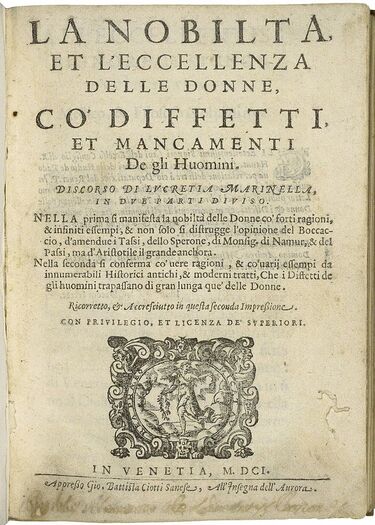

Image info: The title page of Lucrezia Marinella's La nobilita, et l’eccellenza delle donne. Published in Venice 1601. Source: http://luna.folger.edu/luna/servlet/s/184k1c Lucrezia Marinella was born in 1571 in Venice. She was the daughter of natural philosopher and physician, Giovanni Marinelli. Giovanni encouraged Marinella’s education and provided her with important literature covering subjects like medicine, biology, and philosophy. Giovanni was well established as a physician publishing many medical treatises, two of which focused solely on women. Unfortunately, nothing is known of her mother who may have died in childbirth. Little is known of Marinella’s personal life as she lived secluded and devoted to her studies and writing. From her will, we know Marinella married physician Girolamo Vacca and had two children, Antonio and Paulina. She died on October 9th, 1653 of quartan fever, a form of malaria.

Marinella published poetry, philosophical texts, and religious works throughout her lifetime with the exception of a period of silence from 1606-1617 following her marriage to Girolamo. As far as we know, Marinella did not leave behind any personal letters or memoirs. Her most famous work, The Nobility and Excellence of Women and the Defects and Vices of Men, was published in 1600. This text served as a response to an anti-women treatise published a year earlier by Giuseppe Passi entitled, The Defects of Women. Marinella’s Nobility defends the superior virtue and nature of women in comparison to men. For the next few weeks, I will be looking at various passages from the Nobility to explore her feminist and philosophical insights and beliefs. During the Renaissance, Venice served as a major point of trade in Europe. With a flourishing economy, the city soon became a center for tourism, art, and culture. After adopting the printing press in the early 16th century, Venice began to produce many important works of various Greek and Roman writers. Despite the city’s freedom from the censorship of the Church, religious literature increased in production due to the Counter-Reformation in the 16th century. After the success of the Protestant Reformation, Catholic leaders fought to implement their religious doctrines in places like Venice. By 1580, there were over 60 religious households in Venice filled with thousands of clergymen, friars, monks, and nuns. Both inside and outside of these religious institutions, the production of literature backing the Counter-Reformation called for Catholic values in the home. The virtuous woman was asked to be chaste, modest, obedient, and complementary to their household and husband. As an active publication center, however, Venice also produced non-religious and anti-religious texts. Some of these works were written by Venetian women with the means to an education. They produced texts outside of and in response to the religious ideals encouraging women to serve as tokens of Catholic morality where they would be judged by their ability to perform as devout mothers and obedient wives. Over the next several months this blog will focus on four Venetian female philosophers: Veronica Franco (1546-1591), Moderata Fonte (1555-1592), Lucrezia Marinella (1571-1653), and Arcangela Tarabotti (1604-1652). By examining selected passages from their texts, we will look to highlight the nuance and significance of the feminist and philosophical insights made by these women during this time.

--MP |

Authors

Jacinta Shrimpton is a PhD student in Philosophy at the University of Sydney. She is co-producer of the ENN New Voices podcast Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed