|

In reading chapter III of The Nobility and Excellence of Women and the Defects and Vices of Men, I am most interested in Marinella’s appeal to the philosophies of Aristotle and Plato in establishing her bold feminism. Marinella argues that the natural beauty of women reveals the divine excellence of their souls. She writes:  So if women are more beautiful than men, who, as can be seen, are generally coarse and ill-formed, who can deny that they are more remarkable? Nobody, in my opinion. Thus it can be said that beauty in a woman is a marvelous spectacle and a miracle worthy of respect, though it is never fully honored and respected by men. But I wish to go further and show that men are obliged and forced to love women, and that women are not obliged to love them back, except merely from courtesy. I also wish to demonstrate that the beauty of women is the way by which men, who are moderate creatures, are able to raise themselves to the knowledge and contemplation of the divine essence. (62) Marinella first argues that women’s being naturally more beautiful than men reveals the superiority of their souls. She writes, “The greater nobility and worthiness of a woman’s body is shown by its delicacy, its complexion, and its temperate nature, as well as by its beauty, which is a grace or splendor proceeding from the soul as well as from the body” (57). In order to argue that one’s bodily appearance mirrors the state of one’s soul, Marinella appeals to the idea of the hylomorphism found in Aristotle where the soul is the form of the body and body is the matter of the soul. She asks, “What is the form of the body if not the soul? The greatest poets teach us clearly that the soul shines out of the body as the rays of sun shine through transparent glass” (57). The soul, acting as the form of the body, serves as a template for the appearance of the body and, in its bodily existence, reveals the true nature of the being. The more beautiful a woman’s body is, then, according to Marinella, the more beautiful her soul will be. In comparison to women, however, “all men are ugly” and therefore, inferior in their souls (63). With Platonism in mind, Marinella argues that the origin and cause of the external beauty of women is God. God uses the forms, such as beauty, to fashion the external world in the most perfect way. Marinella describes God as “the minister who takes [beauty] … from every other source of perfection and excellence” in order “to create this rich and esteemed treasure house of beauty” (62). Corporeal beauty, then, is personally bestowed by God onto only the worthy creatures of the world (59). Great beauty, like that seen in the bodies of women, reveals a divine nobility and excellence in the being. She writes, “Each writer, Platonist, and poet affirms that beauty comes from God… Divine beauty is, therefore, the first and principal cause of women’s beauty, after which come the stars, heavens, nature, love, and the elements” (60). Like other beauties in the external world, the beauty of women stems from God. Men, however, do not have this beauty. This disparity, according to Marinella, shows that men are less worthy beings than women who are chosen to embody a divine form such as beauty. Most interestingly, Marinella concludes that if women are more beautiful than men, and if this beauty originates in God, then men are obligated to love and contemplate the beauty of women because it will lead them to knowledge of God. She asks, “What poet is there, however coarse, who does not state openly that beauty is the path that guides us directly to the contemplation of divine wisdom…beauty, not being earthly but divine and celestial, always raises us toward God, from whom it is derived” (66). Marinella’s argument here positions women as invaluable gateways to God and beauty itself. In this way, women, by their very nature, demand worship and love while men do not. Nodding to Homer, Marinella describes this phenomena as a “golden chain” (66). Similar to Diotima’s Ladder of Love, found in Plato’s Symposium, Marinella describes our love for physical beauty as a way of ascension to higher forms of beauty. First, we see “corporeal beauty” which is “gazed at and considered by the mind, through the means of the outer eye” (66). In admiration of this beauty, we “ascend” and look “with the internal eye at the soul that, adorned with celestial excellence, gives form to the beautiful body” (66). In contemplation of the soul, we consider the “angelic spirits” and “this contemplative mind seats itself within great light… of the one who supports the chain” (66). In appreciating corporeal beauty, we are led to “delight in Him” and are “made happy and blessed” (66). Men, then are obligated to contemplate the beauty of women because they will be naturally led to a contemplation of the divine. Marinella defends the superiority of women with an appeal to Aristotle’s hylomorphism, Plato’s forms, and by arguing that their bodily beauty reflects their beautiful souls which lead men to knowledge of God. --MP Text source: The Nobility and Excellence of Women, and the Defects and Vices of Men. Edited and translated by Anne Dunhill, The University of Chicago Press, 1999.

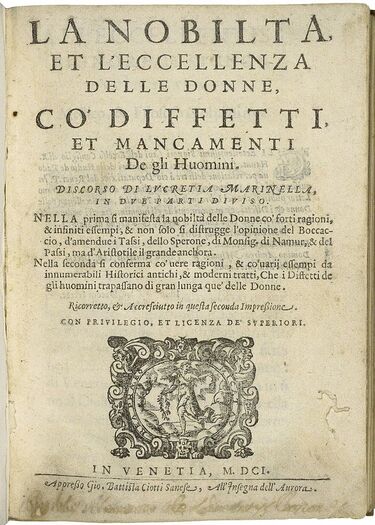

Image info: The title page of Lucrezia Marinella's La nobilita, et l’eccellenza delle donne. Published in Venice 1601. Source: http://luna.folger.edu/luna/servlet/s/184k1c

1 Comment

Towards the end of the second day of Fonte’s Worth of Women, she defends the beauty of the mind and spirit as superior to the beauty of the body:

Although Fonte ultimately concludes that the mind and spirit are superior to the body in quality and beauty, she does not deny the merit of a beautiful body and begins by highlighting the benefits of our corporeal form. The value of the body, according to Fonte, comes from its power to inspire an initial “love” and “desire” for one another. When we meet another person, the appearance of their body “is the first to present itself to our eye and our understanding.” Given our limited perspective, we are directed by our physical desires in our first evaluation of potential lovers. Fonte acknowledges the great influence of a beautiful appearance as she writes, “You’re quite right when you say that in the short term what we see and what pleases the eye has far more power over us than what we cannot see or grasp in an instant” (207). The power of the corporal form to attract, according to Fonte, is greater than the power of the invisible mind and spirit. Yet, this same power leads lovers to desire a fragile, mortal, and inferior kind of beauty.

Unlike the body, Fonte argues, the mind and spirit are truly worthy of our love. Not only do the mind and spirit “[reside] in a nobler part of us,” their very quality exceeds that of our corporeal form. The beauty of the mind and spirit, Fonte argues, “are the kind of beauties that do not fade or wither, but last our whole lives and even live on after our deaths, in our fame” (207). Their ability to withstand the costs of time make the mind and spirit superior to “corporeal beauty” which is “like a fragile flower…fall wilted and dry to the earth.” While the body always falls subject to “illness…fatigue or gradual aging,” inevitably losing its beauty, the beauty of the mind and spirit persists in the face of adversity and escapes the ugly consequences. The superiority of the mind and spirit, then, comes from their infinite beauty which cannot be damaged or lost. Most interestingly, Fonte highlights the moral dimension of the mind and spirit. She describes their beauty as “virtue in its various forms” with “glories” that even the poets cannot capture. In this way, the mind and spirit have an innate and “divine” worth in their nature. Fonte also argues that the mind and spirit “belong” to us in a way our bodies do not. While our bodies change and lose their beauty as we age or fall ill, the beauty of our mind and spirit “inalienably belongs to us”. For being impervious to change and having a moral nature, the mind and spirit are of “a nobler quality” in comparison to the body. It is important to note that the mind and spirit are not entirely separate from the body in love. The value of the body exists within its power to ignite a carnal attraction in the mind. However, overall, the body’s vulnerability and volatility makes it inferior to the impenetrable mind and spirit. For these reasons, Fonte concludes that the lover who desires their beloved for their bodily attributes ignores “what is more important in us and more worthy” of being a reason for love: the beautiful, superior, and “immortal” spirit and mind. --MP Text source: The Worth of Women: Wherein Is Clearly Revealed Their Nobility and Superiority to Men. Edited and Translated by Virginia Cox, The University of Chicago Press, 1997. Image info: Blessed Soul, illustrated by Guido Reni, Italian, published between 1640 and 1642 https://artvee.com/dl/blessed-soul |

Authors

Jacinta Shrimpton is a PhD student in Philosophy at the University of Sydney. She is co-producer of the ENN New Voices podcast Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed