ENN New Voices: The Political Philosophy of Frederick Douglass: Interview with Phil Yaure10/31/2022 In this episode, Olivia speaks with Phil Yaure – assistant professor of philosophy at Virginia Tech University – about the political philosophy of Frederick Douglass. Douglass was born into slavery, but eventually became one of the most influential black abolitionists of the 19th century after escaping his enslaved condition and learning to read and write. Phil’s research focuses on Douglass as a political philosopher, with special concern for Douglass’s conception of the US constitution as an anti-slavery document and his belief that citizenship is a function of one’s contribution to a polity (in contrast to thinking of citizenship as a status that is conferred upon someone by the powers of the state). Phil argues that Douglass considers abolitionist resistance itself to be a way of contributing to American society, which leads to the conclusion that enslaved people fighting against the injustice of slavery make themselves American citizens in doing so. We also discuss the philosophical value of the autobiography genre, and Phil offers listeners some recommendations for where to begin if they want to incorporate Frederick Douglass into their history of philosophy courses.

Further Reading Autobiographies: Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (by Douglass, originally published 1845) My Bondage and My Freedom (by Douglass, originally published 1855) The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (by Douglass, originally published 1881 and revised 1892) Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (by Harriet Jacobs, originally published 1861) Select Speeches by Douglass: “The Free Negro’s Place is in America” (delivered 1851) “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” (July 5 Speech) (delivered 1852) “Claims of our Common Cause: Address of the Colored Convention held in Rochester, July 6-8, 1853” (delivered 1853) Other Sources Mentioned: Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857) Birthright Citizens, Martha S. Jones (Cambridge University Press, 2018) Immigrants and the Right to Stay, Joseph H. Carens with Deborah Chasman (MIT Press, 2018) Immigration and Democracy, Sarah Song (Oxford University Press, 2019) To listen to this episode, please visit our podcast page.

0 Comments

In this episode, Haley Brennan speaks with Dalitso Ruwe, Assistant Professor of Black Political Thought at Queen’s University, about his project of locating and understanding genealogies of Black and African philosophy. We talk about 18th century ontological and Biblical arguments against slavery, the relationship between practical and intellectual revolutions, and what it means to disrupt a system. We also discuss the value of each person’s own philosophical genealogy, and how to find philosophical content in a text. This episode is the first of a series of interviews with New Narratives Postdocs, past and present.

Select Bibliography Frederick Douglass, “Letter from Frederick Douglass to his old master: extracted from the ‘North star’." The Derrick Bell Reader, edited by Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic. James W. C. Pennington, The Fugitive Blacksmith: or, Events in the History of James W. C. Pennington, Pastor of a Presbyterian Church, New York, Formerly a Slave in the State of Maryland, United States Negro Orators and their Orations, edited by Carter G. Woodson. Lift Every Voice: African American Oratory, 1787-1901, edited by Philip S. Foner and Robert Branham. Early Negro Writing, 1760-1837, edited by Dorothy Porter. Angela Davis, Abolition Democracy: Beyond Prisons, Torture, and Empire. John Henrik Clarke, Critical Lessons in Slavery and the Slave Trade: Essential Studies and Commentaries on Slavery, in General, and the African Slave Trade, in Particular. Elizabeth McHenry, Forgotten Reader: Recovering the Lost History of African American Literary Societies To listen to this episode, please visit our podcast page. In this episode, Olivia Branscum speaks with Nastassja Pugliese, Assistant Professor of Philosophy at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. We talk about the life, work, and reception of the nineteenth-century Brazilian philosopher, Nísia Floresta Brasileira Augusta (born Dionísia Gonçalves Pinto in 1810). Nastassja and I talk about Nísia’s philosophy of education, her enlightenment critique of slavery and colonialism, and the common misconception that Nísia translated the work of Mary Wollstonecraft. Though only one of Nísia’s essays has been translated into English, listeners can find some of her writings in French and Italian, and should keep an eye out for Nastassja’s forthcoming introduction to Nísia with Cambridge University Press. Further Reading Primary Texts By Nísia Floresta: Direitos das mulheres e injustiça dos homens (Women's rights and injustice of men), 1832 Páginas de uma vida obscura (Pages of a dark life), 1855 Opúsculo humanitário (Humanitarian brochure), 1853 A lágrima de um Caeté (The tear of a caeté), 1847 “Woman,” translated by Livia A. de Faria in 1865 By others: Woman not inferior to man, or, A short and modest vindication of the natural right of the fair-sex to a perfect equality of power, dignity, and esteem, with the men, by the anonymous “Sofia/Sophia,” 1739 Woman’s superior excellence over man, or, A reply to the author of a late treatise entitled, Man superior to woman…, by the anonymous “Sofia/Sophia,” 1740 The Woman as Good as the Man: Or, The Equality of Both Sexes, by Poulain de la Barre, trans. A. L., London: N. Brooks., 1677 Secondary Texts Gender, Race and Patriotism in the Works of Nísia Floresta, by Charlotte Hammond Matthews “Overthrowing the Floresta-Wollstonecraft Myth for Latin American Feminism,” by Eileen Hunt Botting and Charlotte Hammond Matthews Nísia Floresta, by Nastassja Pugliese, under contract with Cambridge University Press (2023) [Originally published on Facebook April 14, 2021]

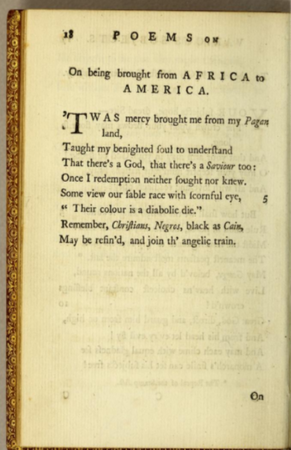

Our first poem of Phillis Wheatley is called “On Being Brought from Africa to America”, and it was published in 1773 in her poetry collection “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral”. We provide a link to the digitized version of her collection at the end of the post. Here is the poem: ‘Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land, Taught my benighted soul to understand That there’s a God, that there’s a Saviour too: Once I redemption neither sought nor knew. Some view our stable race with scornful eye, “Their colour is a diabolic die.” Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain, May be refin’d, and join th’angelic train. There are some interesting conflicts. Firstly, Phillis opens her poem saying that “ ‘twas mercy” who brought her, not slavery. Secondly, she calls her land pagan as if she ignores (we don’t know whether voluntarily or not) the sacrality of the beliefs of her homeland. The third line reinforces that idea, as if there was no God, no “saviour” in Africa, which makes us to wonder if Phillis accepted her past or not. In the fourth line, redemption was not sought by her maybe because she did not know about it. It seems that ignorance makes us away from redemption. However, that same ignorance can be found in America too because some “view our stable race with scornful eye” believing that “their colour is a diabolic die”. This apparent shift of where ignorance lies makes the end of the poem ambiguous: to whom is she talking? Who is her audience? Is she asking all Christians to remember that “Negros”, who are “black as Cain, may be refin’d, and join th’angelic train” or is she asking everyone to remember that both Christians and “Negros” could be “black as Cain”, and that both “may be refin’d, and join th’angelic train”? Finally, was this ambiguity intentional by the poet? What do you think? Digitized Version [Internet Archive]: https://archive.org/.../poemsonvarioussu.../page/18/mode/1up [Originally published on Facebook March 31, 2021]

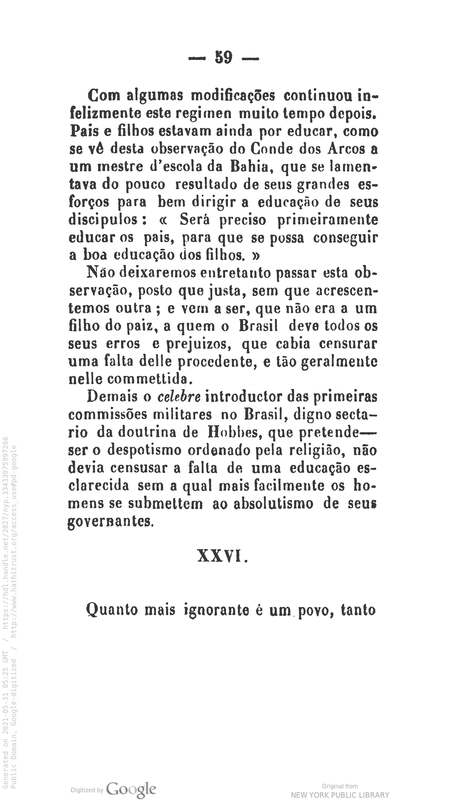

Our last post on Nísia Floresta is from Opúsculo Humanitário, which is the same book from our first post, and is about women’s education. Here is the passage: XXVI (p.59 of the book; 69 of the digitized version) “The more ignorant a nation is, the easier it is for an absolute government to exercise its unlimited power over it. It is from that principle, so contrary to the progressive march of civilization, that most men are against making easier how women cultivate their spirit. However, this is a mistake that has been and always will be contrary to the prosperity of nations as well as is contrary to the domestic fortune of men. (…) Just as a paternal government is the most proper one to make people happy, and a properly cultivated intelligence of those nations is the best incentive for them to fulfill their duties, so too is moral education the safest guide to women. It is the pole star that indicates their north, in the fragile struggle in which they have to navigate as a ship in the sea, a sea seeded with abrolhos (pointed coral reefs), which is called life. The lack of a good education is the primary cause that contributes to women to lose their north, which is nothing else but morality, in the midst of the corruption of society. Always seeking to hold their intelligence, to weaken their senses, they make women unable to occupy, as they should to begin with, the care of purifying their heart; women would never advantageously achieve such thing if their intelligence remains without culture.” As we have seen, Nísia Floresta was against slavery because it is a form of oppression of one people over another. Such oppression can be instantiated in many varieties: it can manifest on basis of color (Europeans to Africans), political views (Italian liberals versus their government and Brazilian liberals versus the Empire), or culture (colonization over the First Natives). This passage shows us that Nísia thinks that lack of education could be another instantiation of oppression because it willingly hinders the moral development of human beings. Since men were “against making easier” for women to learn, men were willingly hindering women’s moral development. Therefore, men were oppressing women. Thus, Nísia finds a common ground between colonized First Natives, enslaved people and women: they were all devoid of education. Worse than that, they were deprived of education by the oppressor, whoever it be. Further, Nísia compares the political influence of an absolute government over an ignorant nation to the power of men over women. Such comparison allows us to consider despotic governments as oppressors too. Thus, we may say that Nísia was against a universal form of oppression, a form that can be instantiated differently. If such oppression is justified by color, we call Nísia an abolitionist; if it is justified by sex, we call her a feminist, and so forth… However, I cannot make something of “a paternal government is the most proper one to make people happy”. She seems to be listing kinds of “guides”. Moral education is “the safest guide” for women. Cultivated intelligence is “the safest guide” for a nation that seeks the fulfilment of its duties. A paternal government is “the safest guide” to make people happy. Was she defending paternal governments or was she just saying that it does not matter how bad a ruler is, if the ruler rules paternally, then the people will not care? If the latter, she may have said that ironically, criticizing paternal governments. __ Retrieved from: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433075997266... Original in Portuguese: “Quanto mais ignorante é um povo, tanto mais fácil é a um governo absoluto exercer sobre ele o seu ilimitado poder. É partindo deste princípio, tão contrário à marcha progressiva da civilização, que a maior parte dos homens se opõem a que se facilite à mulher os meios de cultivar o seu espírito. Porém, é este um erro, que foi e será sempre funesto à prosperidade das nações, como à ventura doméstica do homem. (...) Assim como um governo paternal é o mais próprio a fazer a felicidades dos povos, e a inteligência destes devidamente cultivada o melhor incentivo para o exato cumprimento de seus deveres; assim também a educação moral é o guia mais seguro da mulher, a estrela polar que lhe indica o norte, no frágil batel em que ela tem de navegar por esse mar semeado de abrolhos, a que se chama vida. A falta de uma boa educação é a causa capital, que contribui para que a mulher, no meio da corrupção da sociedade perca esse Norte, o qual não é outro mais que a moral. Procurando-se sempre prender-lhe a inteligência, enfraquecer-lhe os sentidos, inabilitam-na para ocupar-se, como devia, antes de tudo do cuidado de purificar o seu coração; o que nunca poderá ela vantajosamente conseguir se a sua inteligência permanecer sem cultura.” Translated by Matheus Iglessias Mazzochi -MM [Originally posted on Facebook March 24, 2021.]

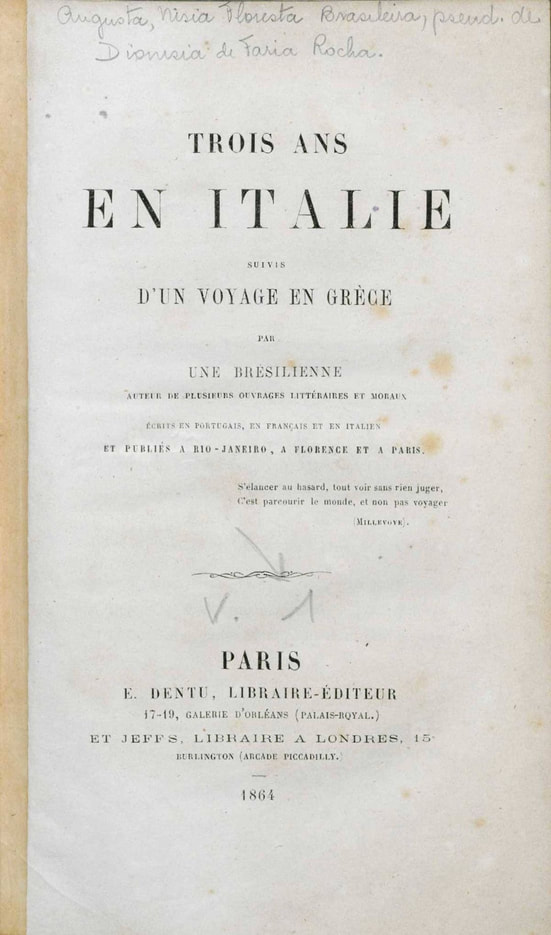

Our fourth post on Nísia Floresta is from “Trois ans en Italie: suivis d’un voyage en Gréce” (Three years in Italy followed by a trip to Greece). This book was published in 1864 in France, but only was translated into Portuguese in 1998. The book is not only a journal of her trips throughout Italy and Greece, full of descriptions of the landscapes and architecture; it is an analysis of the history and political development of those nations. In it, Nísia foresees the Italian Unification [1]. Here is an interesting passage: “If such rebellions [2] were never to be excusable, (…) could the same be said about the savage representatives of noble races (the black enslaved), whom are tortured with humiliating punishments? Furthermore, if war, this infernal scourge whose existence must be banned among all civilized people, can be somehow excused, then it must be done to free our land against the tyrant invaders whom claimed themselves sovereigns. Italy has been tormented, not for days, months, or years, but for centuries, by the despotic yoke of all kinds of conquerors. Its war, therefore, is excusable and even just (…) Italy has risen because its brave sons escaped from the heavy prisons in which they were chained by their tyrants. The spoiled motherland, looking at its noble sons, divided and enslaved by the ambitious despotism of foreign usurpers, finally regained freedom and, likewise, its rights” (pp.317-318). This is a subtle passage. If the Italian rebellions are not excusable for fighting against oppression and for the right to be free, then the same could be said to any rebellion by “the savage representatives of noble races”. But we do consider the Italian rebellions excusable. So, we must consider as excusable any rebellion made by the “noble races”. And by “noble races” Nísia means the black enslaved. It is a powerful analogy and it is logically valid (it is a Modus Tollens). She goes on to state the reasons of the Italian rebellions, leaving us to continue her analogy. Their rebellions are excusable because they fight against “tyrant invaders whom claimed themselves sovereigns”. This is a just cause for Nísia. The Italians were enslaved by “ambitious despotism of foreign usurpers” and they just seek freedom and rights. Is not that what happened in Africa with the African people? Since both Italians and Africans share the same burden of slavery by foreigners and the claim for freedom, to advocate for the Italian unification would be to advocate against slavery. Here, “slavery” is meant in the broad sense: of one nation over another. Thus, it does not reference the color, the language, or the culture of the nation. If one nation is oppressing, enslaving another, it is not right. Thus, any rebellion that claims freedom and rights is excusable and justified. In one single passage, Nísia praises the Italian unification and defends abolitionism. ----- Retrieved from: https://memoria.ifrn.edu.br/.../Tr%c3%aas%20anos%20na... Original in French: 1st Volume: http://objdigital.bn.br/.../drg291826/drg291826.html... 2nd Volume: http://objdigital.bn.br/.../drg1414580/drg1414580.html... [1] Also known as “Risorgimento” (Resurgence), the Italian Unification was the historical process which unified Italian kingdoms into one, resulting the Kingdom of Italy in March 17th, 1861. It was a consequence of the ideas of French revolution that were brought by Napoleon’s troop to Italy when he was at war with Austria. Here is a good article of Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/place/Italy/Unification [2] Here Nísia is referring to the many rebellions that were emerging in Italy prior to its unification. She explains them in previous pages. Although King Francisco II defeated Garibaldi’s troops in Naples, Garibaldi himself won battles against General Landi in Sicily, such as the battle of Calatafimi, and in Munrriali. * Se a revolta jamais fosse desculpável, (...) o mesmo poderia se afirmar em relação a selvagens representantes de raças nobres (escravos negros), a quem se tortura com degradantes castigos? Além disso, se a guerra, flagelo infernal cuja existência deve ser banida dentre todos os povos civilizados, pode ser de alguma forma desculpada, é preciso ser feita para livrar a nossa terra dos tiranos invasores que se fizeram soberanos. A Itália gemeu, não por dias, meses ou anos, mas durante séculos, sob o jugo despótico de todo tipo de dominadores. Sua guerra, pois, é desculpável e até mesmo justa, (...) A Itália ressurgiu em virtude de seus bravos filhos terem escapado das pesadas cadeias com que foram acorrentados por seus tiranos. A espoliada mãe pátria, olhando para seus nobres filhos secularmente divididos e escravizados pelo despotismo ambicioso de usurpadores estrangeiros, recobrou finalmente a liberdade e, da mesma forma, seus direitos. (pp.317-318) Translated by Matheus Iglessias Mazzochi -MM [Originally published on Facebook March 12, 2021]

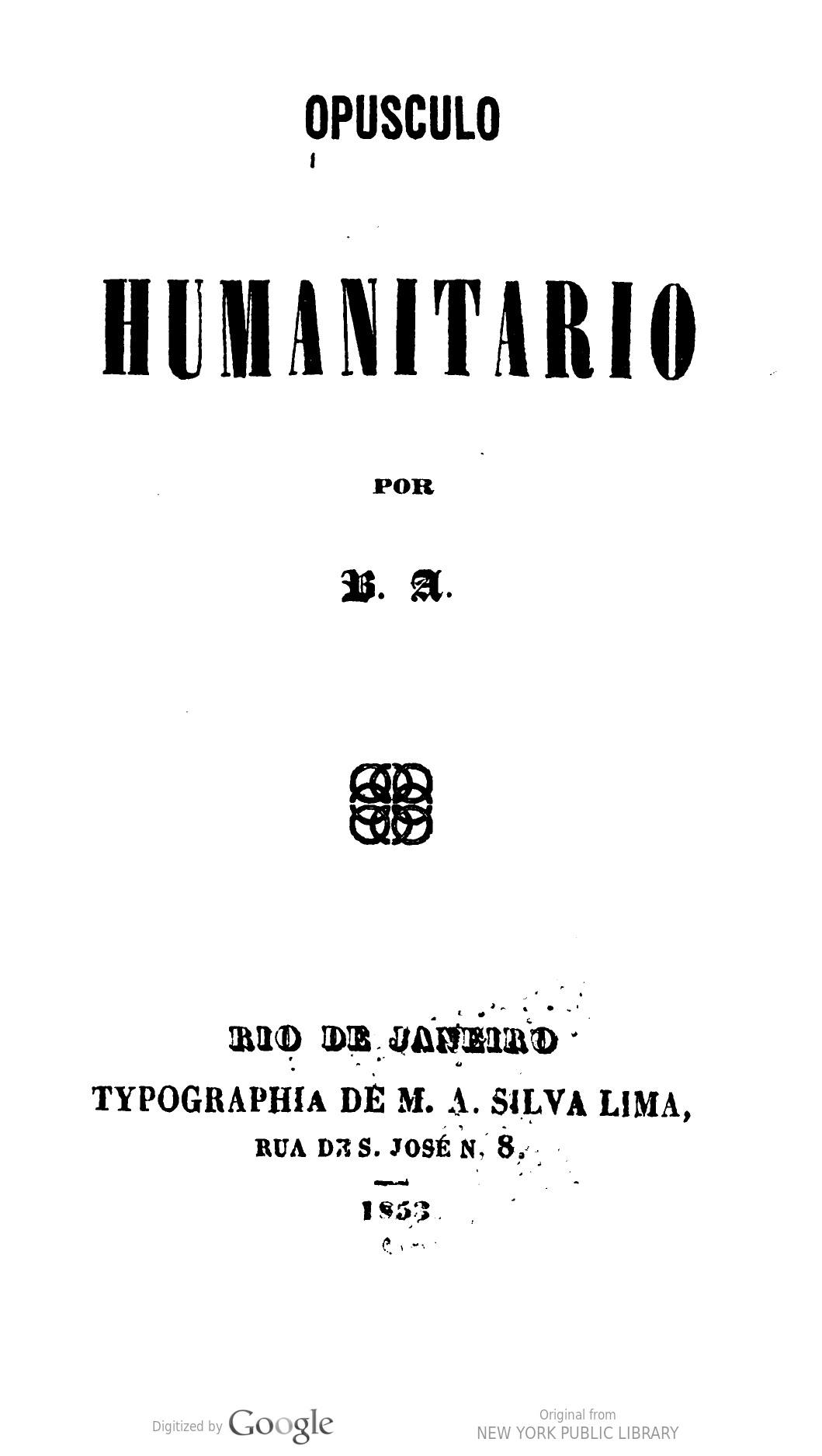

Our first post about Nísia Floresta is from Opúsculo Humanitário, a book she published in 1853 in Rio de Janeiro. In it, Nísia famously argues that society’s progress can only be evaluated by how important women are in it. Although Nísia criticizes (the lack of) women’s education in Brazil in her book, she also talks about slavery. A link to the book is available in the end of this post as well as the original passage (in Portuguese). Chapter XLII (pp. 103-104) “Having all housekeeping being done by slaves, the girl finds herself surrounded by pernicious lessons since her first infancy. She observes behaviours and listens to words of such unfortunate race (people?), which is demoralized by captivity and condemned by the whip. Her sensibility gradually becomes familiar with such distressing show, which repeats almost daily in front of her; it is not rare to see her (with horror we say) inflicting the cruelest treatment to her own wet nurse who breastfed her and is indifferently sold or rented as a useless burden. Such revolting ingratitude is one of the most despicable examples given to that girl, who will become a mother one day and will pass that to her own children! (...) Thus, that sprout of intelligence embedded in her grace develops under the most contrary conditions to its future fulfillment. And no one is mindful that childhood is receiving unfavorable impressions from such art, and as Homer said, it is recorded in the soul as is in a wax table, where all the traits are more or less distinct; impressions that, like a subtle poison, destroys her best natural dispositions.” One of the interesting things implied in this passage is the negative consequences of slavery to human’s development. Since slavery happens at home, “almost daily”, girls are “surrounded by pernicious lessons”. They learn through examples by observing how the slaved person is treated and by listening to the words spoken. Consequently, they learn how to treat other human beings. That is not good. Such education, “by the whip” as Nísia says, “destroys” our “best natural dispositions”, which seems to be the human sensibility. Worse than that, the child becomes ungrateful, apathetic to the woman who breastfed her by growing in such distressing environment. Breastfeeding is one of the first bond that a mother creates to her child. It is a primary human bond. In the end, slavery reduces that human bond to a thing that can be sold or rented. ____ Link to the passage: (https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433075997266...) Todo o serviço do interior das famílias sendo feito entre nós por escravos, a menina acha-se desde a primeira infância cercada de outras tantas perniciosas lições, quantas são as ocasiões em que observa os gestos, as palavras e os atos dessa infeliz raça, desmoralizada pelo cativeiro, e condenada à educação do chicote! Sua nascente sensibilidade se habitua gradualmente a esse espetáculo afligidor, repetido quase diariamente a sua vista; não é raro ver ela (com horror o dizemos) infringir o mais cruel tratamento à própria ama que a amamentou, a qual é alguma vez indiferentemente vendida ou alugada como um fardo inútil, apenas acaba de ser-lhe necessária! Esta revoltante ingratidão é um dos mais detestáveis exemplos dados à menina, que tendo um dia de ser mãe, o transmite por seu turno a seus filhos! (...) Assim, aquele embrião de inteligência envolvido na epiderme de uma graça factícia desenvolve-se nas condições mais contrárias ao seu futuro engrandecimento. E ninguém atenta para as desfavoráveis impressões que de esta arte vai a infância recebendo, e gravando na cera, que conforme a expressão de Homero tem-se na alma, onde se conservam com traços mais ou menos distintos; impressões que semelhante a sutil veneno lhe destroem por vezes as melhores disposições naturais. -MM [Originally published on Facebook 24 February 2021]

Our last post about Mary Ann Shadd Cary is about a sermon. We know little about this sermon, only that it was delivered to an audience in Chatham, Ontario, in 1858. The more we read it, the more complex it becomes. What is it about? Naturally, there is an abolitionist theme. However, how to understand sentences such as “The spirit of true philanthropy knows no sex” or “She (woman) too is a neighbour”? Here is one of the intro paragraphs. “These two great commandments [to love the Lord our God with heart and soul, and our neighbour as our self], and upon which rest all the Law and the prophets, cannot be narrowed down to suit us but we must go up and conform to them. They proscribe neither nation nor sex – our neighbour may be either the oriental heathen, the degraded Europe and or the enslaved colored American. Neither must we prefer sex the slave-mother as well as the slave-father”. This sermon is about more than just the colour of our skin. To me, it’s about love. Love that is both to “the Lord our God”, to “our neighbour”, and to ourselves too. Love “upon which rest all the Law and the prophets”, and that “cannot be narrowed down to suit us”, but that “we must go up and conform to” it. Further in the sermon, Mary Ann Shadd Cary says that we should “waive all prejudices of education, birth, nation or training” to practice that kind of love. That illustrates that she is not talking about sexual or bodily love; she is talking about transcendental love. A love that goes beyond our attributes such as color or sex, for instance. The word “neighbor” could mean everyone. Someone who has a different religious belief than us (“the oriental heathen”), someone whom we don’t respect (“the degraded Europe”), or someone who has been deprived of what we may take for granted (“the enslaved colored American”). But, if we have to consider everyone as our “neighbours” and we have to love them as we would like to be loved, then what would happen to slavery or to inequality? In the end of her sermon, Mary Ann Shadd Cary says that we’re all equal because we share a “common origin”, and were it not for “the monster slavery, we would have a common destiny here.” The meaning of “here” is open to interpretation, but I think she is not limiting her sermon to Chatham, Ontario, April 6th 1858. That is why we’re still talking about her in 2021. --MM [Originally published on Facebook on 17 February 2021]

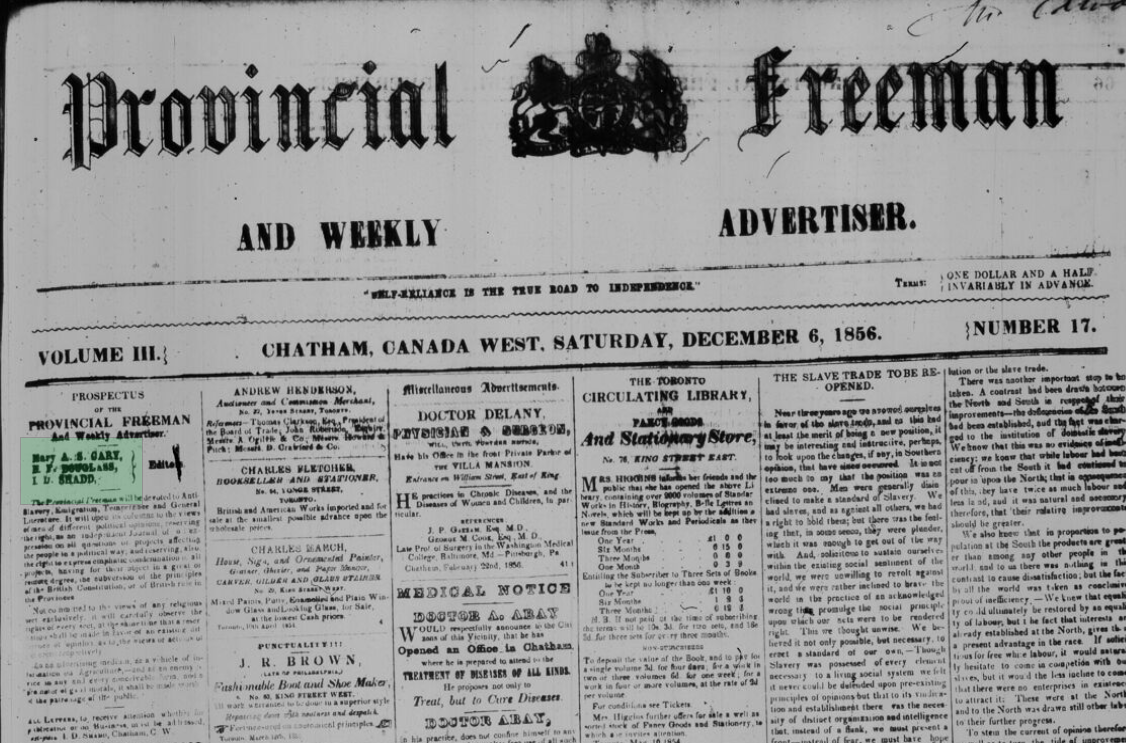

Last week, we talked about Mary Shadd Cary’s A Plea for Emigration. Today, I bring her editorial about the United States presidential election in 1856. Here is a passage: “Instead of a handful of abolitionists, from motives of humanity, the world beholds millions of abolitionists from necessity, and depend upon it there will be hard and bloody work, before the struggle terminate[s]! We heartly deplore the prospect. There is no one so thoroughly depraved! as to love violence for its own sake, but the oppressor of the colored man has forced the necessity” Her words are provocative, aren't they? There will be “hard and bloody” work. Violence will happen whether one protests against slavery or not. The election result shows that slavery is not going to be solved through politics. There is a moral difference among people. It is not a matter of opinion or of facts, it is a matter of moral principles. On one hand, some people believe that slavery is morally acceptable; on the other hand, some do not. Those who do not happen to be oppressed by the former. How to solve that when you do not have rights to protect you and the only people who can recognize those rights into laws are against you? In such scenario, Mary Shadd Cary says that you do not solve this problem without “hard and bloody work”. Violence for its own sake is not morally justifiable, but if all forms of peaceful resolutions are doom to fail, violence as a mean to a greater good may be. It is interesting and cool to see that Philosophy can be found in a newspaper editorial. Next week, we will see that it can be found in a sermon. For historical background: in 1856, James Buchanan was elected the 15th president of the United States. Mary Shadd Cary’s editorial was written two weeks after the election result. She said that “A fearful thing is the result of that last presidential election!”. For her, United States politics was not about being Republican or Democrat; it was about being abolitionist or pro-slavery. Since 1854, the growing apathy towards slaved people, the persecution of abolitionists, and the inefficacy of debates on whether or not slavery was morally acceptable had caused violent riots such as the one known as “Bleeding Kansas”. Mary Shadd Cary’s editorial was predicting that things were going to get worse. Five years after Mr. Buchanan’s election, the United States entered in civil war. --MM Picture retrieved from Canadiana - by Canadian Research Knowledge Network (CRKN) – for research use: [Originally posted to Facebook 11 February 2021]

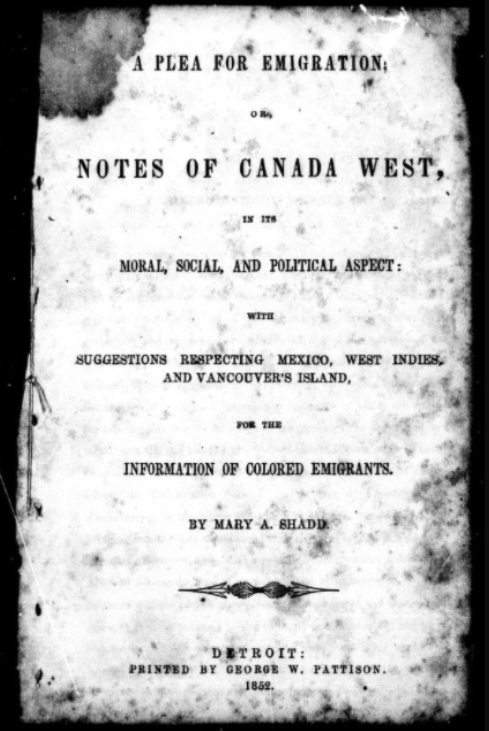

Today I’m going to talk about A Plea for Emigration, the first book published by Mary Shadd Cary. After the Second Fugitive Slave act was passed, life in the United States became even more dangerous. People were looking for a better place to live and Canada was one of those places. Noting the “absence of condensed information accessible to all”, Mary Shadd writes A Plea for Emigration in 1852. As the title suggests, the book not only informs, but pleads. Go to Canada. There the summers are short, people speak mostly French, and there are as many beautiful rivers and streams as apples. However, that seems to be beside the point. There is a passage that I want to highlight. “Lands out of the United States, on this continent, should have no local value, if the questions of personal freedom and political rights were left out of the subject, but as they are paramount, too much may not be said on this point. I mean to be understood, that a description of land in Mexico would probably be as desirable as lands in Canada, if the idea were simply to get lands and settle thereof; but it is important to know if by this investigation we only agitate, and leave the public mind in an unsettled state, or if a permanent nationality is included in the prospects of becoming purchasers and settlers”. The point seems to be that personal freedom and political rights are paramount. But what does she mean by that? To have the possibility to not only buy a land, but also to be a settler. To belong to a community, to have a permanent nationality. Maybe to vote and being a voter, to have rights or titles, to belong in a State. To be respected, protected and allowed to pursue a life with dignity. It is not just about whether the land itself is fertile or not. If it were, there would be no difference between Canada, Mexico or the United States. All lands could be fertile, but not all lands are equal. Picture retrieved from Internet Archive for research use only: https://archive.org/details/cihm_47542/page/n5/mode/2up -MM |

Authors

Jacinta Shrimpton is a PhD student in Philosophy at the University of Sydney. She is co-producer of the ENN New Voices podcast Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed