|

In this special collaborative episode, Haley and Olivia speak with Élaina Gauthier-Mamaril, a philosopher and podcaster who produces and hosts the Philosophy Casting Call podcast. Philosophy Casting Call shines a spotlight on thinkers, topics, and themes that are underrepresented in academic philosophy, which listeners will recognize as a mission dear to our own podcast as well. We highly recommend giving Philosophy Casting Call (and Élaina’s other podcasts) a listen! Our conversation focuses around the theme of podcasting as scholarship, but we reflect on a range of topics throughout, including getting started in podcasting, the differences between general-audience podcasting and podcasting for scholarly audiences, how podcasting has changed our other work in philosophy, and how each of our podcast journeys brought us to where we are today!

To listen to this episode, please visit our podcast page.

0 Comments

I was immediately drawn to Veronica Franco after learning she was not only a feminist and poet, but also a sexworker. Franco’s writing is proudly erotic and boldly explicit as she describes her life as a courtesan. To me, Franco’s unapologetic confidence in her sexuality exemplifies an aspect of womanhood that even today sometimes feels taboo.

Moderata Fonte’s writing, on the other hand, felt more familiar to me. Fonte presents her philosophy through a dialogue held between women. Although familiar in style, Fonte is exceptional in her character development. While reading, I could feel the camaraderie between the women as they joked about things like the inevitable imprisonment of marriage with a soon-to-be bride. I was moved by the sense of community these women provided each other with (although this serves only as the backdrop to Fonte’s excellent feminism and natural philosophy). While many philosophers appeal to the dialogue form, few create such impressive and dynamic characters who can put forth important ideas in a way that does not feel forced or stiff. Perhaps in a manner less graceful than her predecessors, Lucrezia Marinella also presents strong feminist arguments. Aside from her philosophy, Marinella’s descriptions of men like Aristotle are simply fun to read. Zeroing in on the defects of his work many times throughout her text, Marinella describes Aristotle as “foolish…cruel…a fearful, tyrannical man, and sarcastically, as “our good friend Aristotle.” Marinella is ruthless in her analysis of the works of men like Aristotle, making her overall text a page-turner (an accomplishment which sometimes feels like a rarity in philosophical writing). Unknowingly saving the best for last, I finished my research with Arcangela Tarabotti. In Paternal Tyranny, Tarabotti is explicit in her call for an end to the practice of men forcing women who do not have religious vocations into convents. Tarabotti directs her work at men, bringing them into the dialogue by continuously addressing “you”. Without hesitation, Tarabotti puts these men on trial: “Your lying insulting tongues never cease… You cruel hypocrites… You bloodthirsty butchers… You liars!” Throughout her work, Tarabotti’s anger and hurt is palpable. By the end of the text, I could feel the desperation in her voice as she begged for the most basic form of empathy from the most apathetic oppressors. On a personal note, there is something deeply familiar about Tarabotti’s anger. To me, she seemed most frustrated by the hypocrisy of men who call themselves Christians but fail to uphold Christian values. Of course, this kind of experience of religious groups is not isolated to Tarabotti or 17th century Venice. And so, her frustration seems timeless, and, in many ways, she took the words right out of my mouth. Overall, in reading the texts of these women, I enjoyed engaging with various styles of rhetoric, all of which are strong in personality and conviction. Their work serves as a reminder of the importance of the presence of the perspective and ideas of the oppressed in philosophical discussions.  It is hard to ignore the amusing and explicit contempt employed by Marinella in her prose as she criticizes various male thinkers. Throughout The Nobility and Excellence of Women and the Defects and Vices of Men, Marinella often critiques Aristotle and his claim that women are, by nature, the inferior sex. In rebutting Aristotle, Marinella defends her natural philosophy and advocates for equal opportunity among the sexes. She writes, "But in our times there are few women who apply themselves to study or the military arts, since men, fearing to lose their authority and become women’s servants, often forbid them even to learn to read or write. Our good friend Aristotle states that women must obey men everywhere and in everything and not such for anything that takes them outside their houses. A foolish opinion and cruel, pedantic sentence from a fearful, tyrannical man. But we must excuse him, because, being a man, it is only natural he should desire the greatness and superiority of men and not of women. Plato, however, who was truly great and just, was far from imposing a forced and violent authority. He both desired and ordered women to practice the military arts, ride, wrestle and in short, to instruct themselves in the needs of the Republic… If [women] do not show their skills, it is because men do not allow them to practice them, since they are driven by obstinate ignorance, which persuades them that women are not capable of learning the things they do." (79-80) Marinella argues that, in order to maintain their authority, men do not allow women to receive an education or to practice the military arts. Out of fear, these men repress those, mainly women, who hold the potential to threaten their power. For Marinella, Aristotle serves as a prominent example of this “tyrannical man.” Marinella pits Aristotle against Plato “who was truly great and just.” Unlike Aristotle, according to Marinella, Plato rightly advocates for the training of women in various practices dominated by men such as riding, wrestling, and military arts. Any absence of skill or ability found among women in these fields results only from the lack of education and opportunities available to women. Marinella describes the circular nature of this phenomena as a self-fulfilling prophecy where men keep women from being educated and then become convinced that women cannot learn. According to Marinella, Aristotle’s endorsement of limiting women to household work and excluding them from schooling exposes the ignorance and injustices in his philosophy. Marinella also argues that Aristotle’s natural philosophy, which he uses to defend his anti-women views, fails upon further consideration. Both Marinella and Aristotle hold that a person’s bodily temperature says something about their character or nature. According to Marinella, however, Aristotle argues that men are hotter than women and therefore, more noble. She writes, “The good Aristotle, state[s] that women are less hot than men and therefore more imperfect and less noble. Oh what irrefutable and powerful reasoning! I now believe that Aristotle did not consider the workings of heat with a mature mind, nor what it signifies to be more or less hot, nor what good and bad effects derive from this” (130). Unlike Aristotle, Marinella argues that only moderate heat reflects a noble soul. “Excessive heat,” like that of men, “makes souls precipitous and unbridled” while “little and failing heat…is powerless for the soul’s operations” (130). Marinella declares that “women are cooler than men and thus nobler, and that if a man performs excellent deeds it is because his nature is similar to a woman’s, possessing temperate but not excessive heat” (131). As a defense of women as the superior sex, Marinella argues that Aristotle misunderstands the relationship between temperature and soul as the excessive heat of an individual exposes only the defects of their soul. If men are hotter than women as, according to Marinella, Aristotle believes they are, then they are inferior to women by nature. Not only does Marinella attack Aristotle’s misogyny in advocating for inequal opportunity among the sexes, she also highlights the failures of his natural philosophy in his attacks on the nature and temperature of women. Although decorated with colorful insults and bold sarcasm, Marinella’s arguments against Aristotle clearly reveal her expansive knowledge of thinkers like Plato and her own extensive natural philosophy. -MP Text source: The Nobility and Excellence of Women, and the Defects and Vices of Men. Edited and translated by Anne Dunhill, The University of Chicago Press, 1999.

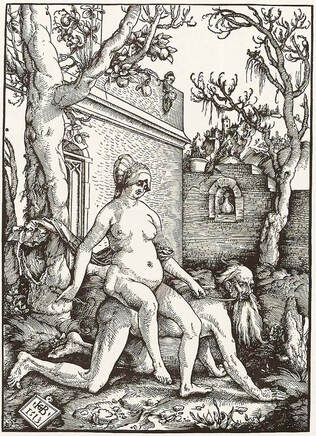

First image info: Image taken from Maria Bandini Buti, Enciclopedia biografica e bibliografica italiana: poetesse e scrittrici (Roma, 1942), vol. 2, p. 10. Source: https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/efts/IWW/Portraits/HTML/A0190.html Second image info: Aristotle and his lover Phyllis. Hans Baldung Grien, 1515. http://www.ibiblio.org/wm/paint/auth/baldung/ In reading chapter III of The Nobility and Excellence of Women and the Defects and Vices of Men, I am most interested in Marinella’s appeal to the philosophies of Aristotle and Plato in establishing her bold feminism. Marinella argues that the natural beauty of women reveals the divine excellence of their souls. She writes:  So if women are more beautiful than men, who, as can be seen, are generally coarse and ill-formed, who can deny that they are more remarkable? Nobody, in my opinion. Thus it can be said that beauty in a woman is a marvelous spectacle and a miracle worthy of respect, though it is never fully honored and respected by men. But I wish to go further and show that men are obliged and forced to love women, and that women are not obliged to love them back, except merely from courtesy. I also wish to demonstrate that the beauty of women is the way by which men, who are moderate creatures, are able to raise themselves to the knowledge and contemplation of the divine essence. (62) Marinella first argues that women’s being naturally more beautiful than men reveals the superiority of their souls. She writes, “The greater nobility and worthiness of a woman’s body is shown by its delicacy, its complexion, and its temperate nature, as well as by its beauty, which is a grace or splendor proceeding from the soul as well as from the body” (57). In order to argue that one’s bodily appearance mirrors the state of one’s soul, Marinella appeals to the idea of the hylomorphism found in Aristotle where the soul is the form of the body and body is the matter of the soul. She asks, “What is the form of the body if not the soul? The greatest poets teach us clearly that the soul shines out of the body as the rays of sun shine through transparent glass” (57). The soul, acting as the form of the body, serves as a template for the appearance of the body and, in its bodily existence, reveals the true nature of the being. The more beautiful a woman’s body is, then, according to Marinella, the more beautiful her soul will be. In comparison to women, however, “all men are ugly” and therefore, inferior in their souls (63). With Platonism in mind, Marinella argues that the origin and cause of the external beauty of women is God. God uses the forms, such as beauty, to fashion the external world in the most perfect way. Marinella describes God as “the minister who takes [beauty] … from every other source of perfection and excellence” in order “to create this rich and esteemed treasure house of beauty” (62). Corporeal beauty, then, is personally bestowed by God onto only the worthy creatures of the world (59). Great beauty, like that seen in the bodies of women, reveals a divine nobility and excellence in the being. She writes, “Each writer, Platonist, and poet affirms that beauty comes from God… Divine beauty is, therefore, the first and principal cause of women’s beauty, after which come the stars, heavens, nature, love, and the elements” (60). Like other beauties in the external world, the beauty of women stems from God. Men, however, do not have this beauty. This disparity, according to Marinella, shows that men are less worthy beings than women who are chosen to embody a divine form such as beauty. Most interestingly, Marinella concludes that if women are more beautiful than men, and if this beauty originates in God, then men are obligated to love and contemplate the beauty of women because it will lead them to knowledge of God. She asks, “What poet is there, however coarse, who does not state openly that beauty is the path that guides us directly to the contemplation of divine wisdom…beauty, not being earthly but divine and celestial, always raises us toward God, from whom it is derived” (66). Marinella’s argument here positions women as invaluable gateways to God and beauty itself. In this way, women, by their very nature, demand worship and love while men do not. Nodding to Homer, Marinella describes this phenomena as a “golden chain” (66). Similar to Diotima’s Ladder of Love, found in Plato’s Symposium, Marinella describes our love for physical beauty as a way of ascension to higher forms of beauty. First, we see “corporeal beauty” which is “gazed at and considered by the mind, through the means of the outer eye” (66). In admiration of this beauty, we “ascend” and look “with the internal eye at the soul that, adorned with celestial excellence, gives form to the beautiful body” (66). In contemplation of the soul, we consider the “angelic spirits” and “this contemplative mind seats itself within great light… of the one who supports the chain” (66). In appreciating corporeal beauty, we are led to “delight in Him” and are “made happy and blessed” (66). Men, then are obligated to contemplate the beauty of women because they will be naturally led to a contemplation of the divine. Marinella defends the superiority of women with an appeal to Aristotle’s hylomorphism, Plato’s forms, and by arguing that their bodily beauty reflects their beautiful souls which lead men to knowledge of God. --MP Text source: The Nobility and Excellence of Women, and the Defects and Vices of Men. Edited and translated by Anne Dunhill, The University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Image info: The title page of Lucrezia Marinella's La nobilita, et l’eccellenza delle donne. Published in Venice 1601. Source: http://luna.folger.edu/luna/servlet/s/184k1c

Here, Fonte highlights the double standard held against women with regards to their sexual relationships. While men receive praise when they have sex, women face shame from society. Relatedly, while men can boast about their sexual conquests, women are expected to hide any sign of their sexual life. Fonte argues that these responses reveal the difference in dignity between the sexes as women treat sex with more nobility than men. Yet, while men are able to find “glory and happiness” in sex, women who engage in the sex act, whether inside or outside of marriage, are necessarily degraded. It is important to note that Fonte does not argue against women feeling shame for having sex. Instead, she agrees the act is shameful but insists the shame derives from the superior sex, women, engaging with the inferior sex, men.

The sexes also experience a stark difference in the dependence they have on their relationships with the opposite sex. To become a “real man,” according to Fonte, one must build a relationship with a woman through marriage. Only after having that relationship can a man achieve “happiness, honor, and greatness.” In contrast, women thrive best when they are given full independence from men. Fonte emphasizes the power of female virginity as a way in which women can achieve divine greatness. A woman, untouched by men, has “something divine about her” and can accomplish “miracles.” Not only does Fonte define men as the inferior sex, she also describes them as a kind of parasite that reduces the value and abilities of women as “intercourse with men abases” women. In this way, men threaten women who seek to reach their full, sometimes divine, potential. Moreover, Fonte examines how women face greater disapproval from society in comparison to men in having sex. Cornelia, a character in the dialogue, explains the hypocrisy of this treatment, especially when it comes from men, and says, “They can keep up these curses and insults all day without once looking down at themselves and seeing that they may need to take some of the blame… if the fault is common to both sexes (as they can hardly deny), why should the blame not be as well?” (90) Once again, Fonte highlights the inequitable treatment of the sexes by society. Men encourage this unfounded response as they do not reflect on their own faults and instead, hurl insults at women who have sex despite taking equal part in the act. Throughout the first half of the dialogue, Fonte reveals the extreme hypocrisy of society in its treatment of men and women as sexual persons while also defending women as the superior sex as seen in their unique ability to thrive independently of men. -MP Text source: The Worth of Women: Wherein Is Clearly Revealed Their Nobility and Superiority to Men. Edited and Translated by Virginia Cox, The University of Chicago Press, 1997. Image info: Cover of Moderata Fonte's Il Merito Delle Donne, illustrated by Domenico Imberti, published in Venice in 1600 Source: http://badigit.comune.bologna.it/books/Moderata_Fonte/scorri.asp In this episode, Haley Brennan talks with Alison Stone, professor in the Department of Politics, Philosophy and Religion at Lancaster University. We discuss the work of British women philosophers of the 19th century, including Frances Power Cobbe, Ada Lovelace, and Harriet Martineau. We cover a range of topics that these philosophers worked on, including animal rights, feminism, ethics, and philosophy of mind. In addition to these topics, we talk about the correspondence that these women had with each other, the influence they had on political movements in 19thc Britain, and where and how to look to find the philosophical writings of women in the period. We also discuss the way that perceived philosophical importance and impact varies across time and place, and how this affects which philosophers we research and teach today.

Works by British Women Philosophers Mentioned in the Episode Unless otherwise specified, all works listed are in the public domain and are available online Frances Power Cobbe, ‘The Rights of Man and the Claims of Brutes’ —, An Essay on Intuitive Morals —, Darwinism in Morals --, ‘Wife-Torture in England’ —, Essays on the Pursuits of Women, with a paper on Female Education —, ‘Why Women Desire the Franchise’ Ada Augusta Lovelace, ‘Sketch of the Analytical Engine’ Harriet Martineau, Illustrations of Political Economy --, ‘Letters on Mesmerism’ —, Autobiography —, with Henry George Atkinson, Letters on the Laws of Man’s Nature and Development Victoria Welby, Signifying and Understanding, ed. Susan Petrilli (De Gruyter, 2009) Further Reading Alison Stone, ed., Frances Power Cobbe: Essential Writings of a Nineteenth-Century Feminist Philosophy (Oxford University Press, forthcoming early 2022) Charlotte Alderwick and Alison Stone, ed., Nineteenth-Century Women Philosophers in Britain and America, British Journal for the History of Philosophy 29, no. 2 (2021) In Capitolo 16, Franco argues that any general weakness found in women comes from a lack of resources and opportunity and not from their nature. Franco wrote this poem as a response to Maffio Venier, a poet who publicly defamed her in his work. She writes,

Franco argues that, given proper “weapons and training,” women would have the same “hands and feet and hearts” as men. While defending the strength of women, Franco confronts an essentialist approach to the sexes. She challenges the idea that qualities like strength and delicacy are mutually exclusive and that either of them belong only to a single sex. She explains that in the same way we find tough, yet cowardly men, we can find delicate and strong women. Seeing women as weaker than men because of their general delicacy, then, fails to capture the complexity of each person as an individual. Franco sees the attack of Maffio as an attack on all women. She promises to “defend all women/ against” men like her attacker and to serve as “an example for them all to follow.” (79-80) In this role, Franco describes how she came to know her own strength. According to Franco, many women, because they lack the right training and tools, feel that they are weaker than men. She writes, “Women so far haven’t seen this is true;/ for if they’d ever resolved to do it,/ they’d have been able to fight you to death.” (70-72) Even Franco admits to feeling “defenseless” and vulnerable to the attacks of men. (22) Yet, after “devoting all [her] efforts to arms,” she came to “no longer fear harm from anyone.” (37-39) Her newfound security taught Franco “that women by nature are no less agile than men.” (34-36) In sharing her own experience, Franco argues that women can escape positions of vulnerability if they are given the same opportunities and resources as men. I think it is important to note that Franco does not ultimately challenge her attacker to a physical fight. Instead, she defends herself as an intellectual. Franco trains with the metaphorical “arms” of language in preparation for this fight. She tells Maffio that he can choose any language to battle in as she is “equally happy with them all,/ since [she has] learned them for exactly this purpose.” (126-127) She describes her attacker’s weapon as, “The sword that strikes and stabs in [his] hand—/ the common language spoken in Venice” and says that she will also fight using her rhetoric. (112-114) Towards the end of the poem she writes,

By defending herself as a skilled writer while serving as a champion of all women, she defends the intellectual capacities of her sex. Franco also highlights how her education and the chance to “practice” her craft has prepared her to win this fight. Again, she shows how the right resources can prepare a woman for any kind of combat against a man. As seen in my previous post, Franco believes that virtue is not found in bodily strength, but in the “vigor of the soul and mind.” (Capitolo 24, 61-62) Thus, in choosing to ultimately defend her superior intellect instead of focusing merely on physical strength, Franco reinforces the argument that women excel in virtue as seen in their superior reason. -MP Image info: Newlywed Venetian Bride, Noble Venetian Matron, Venetian Courtesan (engraving) Anonymous Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris. Lawner. https://venice11.umwblogs.org/venetian-attire-similarities-between-courtesans-and-aristocratic-women/#_edn

I will first look at Franco’s poem, Capitolo 24. Franco wrote this poem as a response to a man who had insulted and threatened another woman, presumably a fellow courtesan. The entire poem is 160 lines. I will examine lines 70-90 as seen below:

Earlier in the poem, Franco argues that virtue lies in the soul and mind and that women “have given/ more than one sign of being greater than men” in this way (65-66). In the excerpt above, Franco outlines the ways in which women show their superiority in virtue. Franco seems to make two arguments here: first, that submission to men serves as an act of virtue and second, that childbearing plays a significant role in both submission and in improving the condition of the world. Through their submission and childbearing, Franco argues, women are superior to men in virtue.

Franco describes the submission of women as an adaptive response to the weakness of men. Women must guide and carry men because men are weak and prone to “fall” without women’s support. Franco implies that because men “do wrong,” they cannot support the weak in the same way women support men. As a result, women must become the submissive party if they want to “avoid pursuing wrongdoing.” Submission is thus a choice women make in order to compensate for the shortcomings of men. Still, Franco reminds the man whom the poem addresses that, if women were to ignore this call to service and reveal their superiority, women would easily “surpass” men. Yet, a woman intentionally “submits to tyrannical, wicked man” and becomes “silent.” The submission of women, for Franco, acts as both a virtue and a reflection of the strength women have in comparison to men. Childbearing, for Franco, exemplifies the virtuous and indispensable submission of women. An end to the submission of women, according to Franco, directly results in an end to childbearing. Franco presents childbearing as a paradigm act of submission. Yet, in providing offspring, women have the unique ability to play a role in improving the condition of the world. For Franco, women bear children so that women do not “ruin the world” and instead, make the world “beautiful.” In this way, submission can be said to empower women as they are able to affect the world in a significant and unique manner by giving birth. For Franco, childbearing embodies the powerful sacrifice women make in order to improve the condition of the world. This submission is also voluntary and actively chosen as a result of the superior reason and morality of women. In the excerpt above, Franco tells the story of why men became the dominate sex. According to Franco, the power of men results directly from the grace and selflessness of women who are wiser and superior in virtue. In order to compensate for the failures of the weaker sex, women submit and support men. The power given to men, however, can be taken back at any time if women refuse to procreate. Yet, their virtuous and reasonable nature leads them to do what is best for the world as a whole and bring the beauty of offspring into the world. The submission of women to men, seen especially in childbearing, exemplifies the virtue and reason of women as they refrain from revealing their true superiority to better serve the world. Our first Venetian female philosopher is Veronica Franco (1546-1591), a 16th century courtesan known for her letters and poetry. Franco was born into a working class family with three brothers, all of whom received an education. Fortunately, her mother encouraged her daughter to study under a tutor alongside her brothers. It was not until after her divorce from Paolo Panizza that Franco, left with a child and the loss of her dowry, became a courtesan for highly esteemed men including Henry III and Domenico Venier. Venier, a famous poet himself and head of a renowned literary academy, provided Franco with great friendship and a space to work on her writing.

Franco’s writings critique the treatment of courtesans by the state and men. Her poetry provides insight into her personal relationships as well as her philosophical endorsement of equality between men and women. In her own defense, Franco makes herself representative of all women and argues that, given the opportunity and resources, women would have physical and mental abilities equal to that of men. Later in her life, Franco published a collection of her correspondence with her clients. Shortly after this publication, however, Franco was accused of witchcraft and her reputation was ruined. Throughout the course of her career, Veronica Franco became known for her esteemed reputation as a courtesan, her defense of equality for women, and her exceptional writing abilities. We will look at selected passages in her ‘Terze Rime’ (1575), a collection of poetry, and selected letters from her “Lettere Familiari a Diversi” (1580), a collection of 50 letters between Franco and her clients. -- MP Image : Jacopo Tintoretto (1575-1594), Portrait of a Lady. Source: Worcester Art Museum. Note: This portrait is taken to be of Franco because her name is written on the lining of the canvas |

Authors

Jacinta Shrimpton is a PhD student in Philosophy at the University of Sydney. She is co-producer of the ENN New Voices podcast Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed