|

In this episode, Olivia Branscum speaks with Nastassja Pugliese, Assistant Professor of Philosophy at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. We talk about the life, work, and reception of the nineteenth-century Brazilian philosopher, Nísia Floresta Brasileira Augusta (born Dionísia Gonçalves Pinto in 1810). Nastassja and I talk about Nísia’s philosophy of education, her enlightenment critique of slavery and colonialism, and the common misconception that Nísia translated the work of Mary Wollstonecraft. Though only one of Nísia’s essays has been translated into English, listeners can find some of her writings in French and Italian, and should keep an eye out for Nastassja’s forthcoming introduction to Nísia with Cambridge University Press. Further Reading Primary Texts By Nísia Floresta: Direitos das mulheres e injustiça dos homens (Women's rights and injustice of men), 1832 Páginas de uma vida obscura (Pages of a dark life), 1855 Opúsculo humanitário (Humanitarian brochure), 1853 A lágrima de um Caeté (The tear of a caeté), 1847 “Woman,” translated by Livia A. de Faria in 1865 By others: Woman not inferior to man, or, A short and modest vindication of the natural right of the fair-sex to a perfect equality of power, dignity, and esteem, with the men, by the anonymous “Sofia/Sophia,” 1739 Woman’s superior excellence over man, or, A reply to the author of a late treatise entitled, Man superior to woman…, by the anonymous “Sofia/Sophia,” 1740 The Woman as Good as the Man: Or, The Equality of Both Sexes, by Poulain de la Barre, trans. A. L., London: N. Brooks., 1677 Secondary Texts Gender, Race and Patriotism in the Works of Nísia Floresta, by Charlotte Hammond Matthews “Overthrowing the Floresta-Wollstonecraft Myth for Latin American Feminism,” by Eileen Hunt Botting and Charlotte Hammond Matthews Nísia Floresta, by Nastassja Pugliese, under contract with Cambridge University Press (2023)

0 Comments

Towards the end of the second day of Fonte’s Worth of Women, she defends the beauty of the mind and spirit as superior to the beauty of the body:

Although Fonte ultimately concludes that the mind and spirit are superior to the body in quality and beauty, she does not deny the merit of a beautiful body and begins by highlighting the benefits of our corporeal form. The value of the body, according to Fonte, comes from its power to inspire an initial “love” and “desire” for one another. When we meet another person, the appearance of their body “is the first to present itself to our eye and our understanding.” Given our limited perspective, we are directed by our physical desires in our first evaluation of potential lovers. Fonte acknowledges the great influence of a beautiful appearance as she writes, “You’re quite right when you say that in the short term what we see and what pleases the eye has far more power over us than what we cannot see or grasp in an instant” (207). The power of the corporal form to attract, according to Fonte, is greater than the power of the invisible mind and spirit. Yet, this same power leads lovers to desire a fragile, mortal, and inferior kind of beauty.

Unlike the body, Fonte argues, the mind and spirit are truly worthy of our love. Not only do the mind and spirit “[reside] in a nobler part of us,” their very quality exceeds that of our corporeal form. The beauty of the mind and spirit, Fonte argues, “are the kind of beauties that do not fade or wither, but last our whole lives and even live on after our deaths, in our fame” (207). Their ability to withstand the costs of time make the mind and spirit superior to “corporeal beauty” which is “like a fragile flower…fall wilted and dry to the earth.” While the body always falls subject to “illness…fatigue or gradual aging,” inevitably losing its beauty, the beauty of the mind and spirit persists in the face of adversity and escapes the ugly consequences. The superiority of the mind and spirit, then, comes from their infinite beauty which cannot be damaged or lost. Most interestingly, Fonte highlights the moral dimension of the mind and spirit. She describes their beauty as “virtue in its various forms” with “glories” that even the poets cannot capture. In this way, the mind and spirit have an innate and “divine” worth in their nature. Fonte also argues that the mind and spirit “belong” to us in a way our bodies do not. While our bodies change and lose their beauty as we age or fall ill, the beauty of our mind and spirit “inalienably belongs to us”. For being impervious to change and having a moral nature, the mind and spirit are of “a nobler quality” in comparison to the body. It is important to note that the mind and spirit are not entirely separate from the body in love. The value of the body exists within its power to ignite a carnal attraction in the mind. However, overall, the body’s vulnerability and volatility makes it inferior to the impenetrable mind and spirit. For these reasons, Fonte concludes that the lover who desires their beloved for their bodily attributes ignores “what is more important in us and more worthy” of being a reason for love: the beautiful, superior, and “immortal” spirit and mind. --MP Text source: The Worth of Women: Wherein Is Clearly Revealed Their Nobility and Superiority to Men. Edited and Translated by Virginia Cox, The University of Chicago Press, 1997. Image info: Blessed Soul, illustrated by Guido Reni, Italian, published between 1640 and 1642 https://artvee.com/dl/blessed-soul On the second day of the dialogue, Fonte explicitly argues that women should receive an education. She writes,

Fonte claims two things here: first, that receiving an education leads to a virtuous life and second, that in withholding education from women, men commit both an ethical and epistemic injustice. With the former claim, Fonte works to rebut the belief held by men that says an educated woman becomes immoral. She argues that, in reality, without an education, “an ignorant person is far more liable to fall into err.” Fonte defends this argument by depicting the common undesirable and uneducated women. These women, such as the “illiterate maid servants,” the “peasant girls and plebeian women,” fold to their sexual desires and easily “give in to their lovers.” Without the opportunity to exercise their minds through reading and writing, these women become “gullible” to the persuasions of men and cannot defend themselves. According to Fonte, uneducated women lack the ability to reason and as a result, must depend on the word and direction of men. Of course, even educated women are subject to the “pricking of the senses,” but their intellect allows them to combat physical temptation. For Fonte, education is just “the pursuit of virtue.” Without schooling, then, women do not have the resources to become virtuous and as a result, they inevitably give into sexual relations.

Fonte’s argument highlights the way in which men have been counterproductive and ineffective in trying to make women more virtuous. Instead of providing them with the necessary tools to defend themselves against lustful desires, men leave them weak and vulnerable. Notice that Fonte does not argue against the belief that women are naturally perverse or driven by their bodily appetites. Instead, she uses this idea as a reason in favor of giving women an education. In this way, Fonte appeals to the beliefs of men. Still, she reveals how, in the name of keeping women from their natural vices, men have inhibited women from achieving a moral life. Fonte presents the characters in her dialogue as exemplary of the benefits of educating women. It is because these women “have read [their] cautionary tales and learnt [their] moral lessons” that they “developed a love for virtue.” Readers of the dialogue, then, can look to Fonte’s characters as proof that education and virtue go hand in hand. In this passage, Fonte argues that a woman can only fight her sexual inclinations through education and that men have wrongfully repressed women who wish to pursue virtue. --MP Image info: The Education of the Virgin Mary, illustrated by Giovanni Francesco Romanelli, Italian, published in Rome in 1630. Text source: The Worth of Women: Wherein Is Clearly Revealed Their Nobility and Superiority to Men. Edited and Translated by Virginia Cox, The University of Chicago Press, 1997.

Here, Fonte highlights the double standard held against women with regards to their sexual relationships. While men receive praise when they have sex, women face shame from society. Relatedly, while men can boast about their sexual conquests, women are expected to hide any sign of their sexual life. Fonte argues that these responses reveal the difference in dignity between the sexes as women treat sex with more nobility than men. Yet, while men are able to find “glory and happiness” in sex, women who engage in the sex act, whether inside or outside of marriage, are necessarily degraded. It is important to note that Fonte does not argue against women feeling shame for having sex. Instead, she agrees the act is shameful but insists the shame derives from the superior sex, women, engaging with the inferior sex, men.

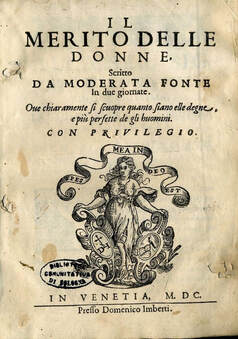

The sexes also experience a stark difference in the dependence they have on their relationships with the opposite sex. To become a “real man,” according to Fonte, one must build a relationship with a woman through marriage. Only after having that relationship can a man achieve “happiness, honor, and greatness.” In contrast, women thrive best when they are given full independence from men. Fonte emphasizes the power of female virginity as a way in which women can achieve divine greatness. A woman, untouched by men, has “something divine about her” and can accomplish “miracles.” Not only does Fonte define men as the inferior sex, she also describes them as a kind of parasite that reduces the value and abilities of women as “intercourse with men abases” women. In this way, men threaten women who seek to reach their full, sometimes divine, potential. Moreover, Fonte examines how women face greater disapproval from society in comparison to men in having sex. Cornelia, a character in the dialogue, explains the hypocrisy of this treatment, especially when it comes from men, and says, “They can keep up these curses and insults all day without once looking down at themselves and seeing that they may need to take some of the blame… if the fault is common to both sexes (as they can hardly deny), why should the blame not be as well?” (90) Once again, Fonte highlights the inequitable treatment of the sexes by society. Men encourage this unfounded response as they do not reflect on their own faults and instead, hurl insults at women who have sex despite taking equal part in the act. Throughout the first half of the dialogue, Fonte reveals the extreme hypocrisy of society in its treatment of men and women as sexual persons while also defending women as the superior sex as seen in their unique ability to thrive independently of men. -MP Text source: The Worth of Women: Wherein Is Clearly Revealed Their Nobility and Superiority to Men. Edited and Translated by Virginia Cox, The University of Chicago Press, 1997. Image info: Cover of Moderata Fonte's Il Merito Delle Donne, illustrated by Domenico Imberti, published in Venice in 1600 Source: http://badigit.comune.bologna.it/books/Moderata_Fonte/scorri.asp Modesta Pozzo, better known by her pen name, Moderata Fonte, was born in 1555 in Venice. Her parents, Marietta dal Morro and lawyer, Girolama Pozzo, belonged to an educated and wealthy class in Venice referred to as the cittadini originari. After Fonte’s parents died within the first year of her life, she was taken in by her maternal grandmother, Cecilia di Mazzi. Fonte received an education at the Santa Marta convent until the age of 9 and then continued an informal education with the help of Prosperi Saraceni, her grandmother’s second husband, and her brother, Leonardo. She was known as an extremely bright student, writing poetry of her own very early in her childhood. In her twenties, Fonte moved in with Saracena Saraceni, the daughter of Cecilia and Prosperi Saraceni, and Saracena’s husband, Giovanni Niccolò Doglioni. Doglioni, with his many connections to Venice’s literary circles, encouraged Fonte to write and helped her to publish. Much of what we know of Fonte comes from Doglioni’s Vita, a biography written on Fonte’s life published in 1600. At the late age of 27, Fonte married Filippo Di'Zorzi, a lawyer and government worker. After only a year and a half of marriage, Di'Zorzi returned Fonte’s dowry as a show of his deep admiration and appreciation of her. Fonte died in 1592, seemingly after complications with the birth of her fourth child.

By the time she was married, Fonte was well established as an exceptionally skilled poet in Venice. Throughout her lifetime, Fonte wrote various romantic and biblical sonnets, ballads, philosophical dialogues, and dramatic plays. Most famously, Fonte wrote a feminist text entitled, The Worth of Women, published after her death in 1600. The Worth of Women is a dialogue between seven Venetian women who discuss the abuse women face in light of the widely held belief that women are, by nature, inferior to men. The women discuss subjects that include the inequality in education, the abuse women endure in their marriages, and other injustices faced regularly by women in Venice. I will be looking at selected passages in The Worth of Women to explore Fonte’s philosophical analysis of gender relations and her response to the injustices faced by Venetian women. -MP Image info: Moderata Fonte (Modesta Dal Pozzo, 1555-1592). The frontispiece of Il merito delle donne. Venezia, Domenico Imberti, 1600. |

Authors

Jacinta Shrimpton is a PhD student in Philosophy at the University of Sydney. She is co-producer of the ENN New Voices podcast Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed