|

[Originally posted on Facebook March 24, 2021.]

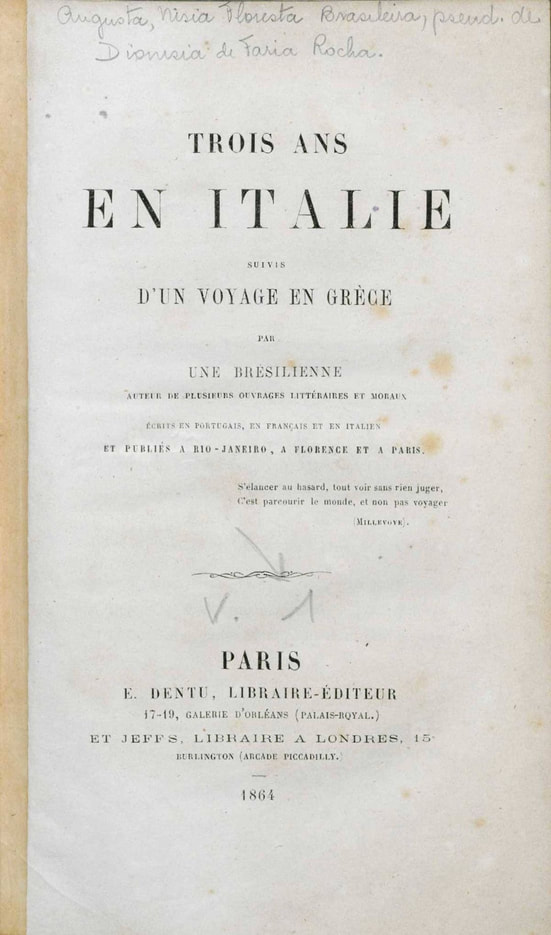

Our fourth post on Nísia Floresta is from “Trois ans en Italie: suivis d’un voyage en Gréce” (Three years in Italy followed by a trip to Greece). This book was published in 1864 in France, but only was translated into Portuguese in 1998. The book is not only a journal of her trips throughout Italy and Greece, full of descriptions of the landscapes and architecture; it is an analysis of the history and political development of those nations. In it, Nísia foresees the Italian Unification [1]. Here is an interesting passage: “If such rebellions [2] were never to be excusable, (…) could the same be said about the savage representatives of noble races (the black enslaved), whom are tortured with humiliating punishments? Furthermore, if war, this infernal scourge whose existence must be banned among all civilized people, can be somehow excused, then it must be done to free our land against the tyrant invaders whom claimed themselves sovereigns. Italy has been tormented, not for days, months, or years, but for centuries, by the despotic yoke of all kinds of conquerors. Its war, therefore, is excusable and even just (…) Italy has risen because its brave sons escaped from the heavy prisons in which they were chained by their tyrants. The spoiled motherland, looking at its noble sons, divided and enslaved by the ambitious despotism of foreign usurpers, finally regained freedom and, likewise, its rights” (pp.317-318). This is a subtle passage. If the Italian rebellions are not excusable for fighting against oppression and for the right to be free, then the same could be said to any rebellion by “the savage representatives of noble races”. But we do consider the Italian rebellions excusable. So, we must consider as excusable any rebellion made by the “noble races”. And by “noble races” Nísia means the black enslaved. It is a powerful analogy and it is logically valid (it is a Modus Tollens). She goes on to state the reasons of the Italian rebellions, leaving us to continue her analogy. Their rebellions are excusable because they fight against “tyrant invaders whom claimed themselves sovereigns”. This is a just cause for Nísia. The Italians were enslaved by “ambitious despotism of foreign usurpers” and they just seek freedom and rights. Is not that what happened in Africa with the African people? Since both Italians and Africans share the same burden of slavery by foreigners and the claim for freedom, to advocate for the Italian unification would be to advocate against slavery. Here, “slavery” is meant in the broad sense: of one nation over another. Thus, it does not reference the color, the language, or the culture of the nation. If one nation is oppressing, enslaving another, it is not right. Thus, any rebellion that claims freedom and rights is excusable and justified. In one single passage, Nísia praises the Italian unification and defends abolitionism. ----- Retrieved from: https://memoria.ifrn.edu.br/.../Tr%c3%aas%20anos%20na... Original in French: 1st Volume: http://objdigital.bn.br/.../drg291826/drg291826.html... 2nd Volume: http://objdigital.bn.br/.../drg1414580/drg1414580.html... [1] Also known as “Risorgimento” (Resurgence), the Italian Unification was the historical process which unified Italian kingdoms into one, resulting the Kingdom of Italy in March 17th, 1861. It was a consequence of the ideas of French revolution that were brought by Napoleon’s troop to Italy when he was at war with Austria. Here is a good article of Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/place/Italy/Unification [2] Here Nísia is referring to the many rebellions that were emerging in Italy prior to its unification. She explains them in previous pages. Although King Francisco II defeated Garibaldi’s troops in Naples, Garibaldi himself won battles against General Landi in Sicily, such as the battle of Calatafimi, and in Munrriali. * Se a revolta jamais fosse desculpável, (...) o mesmo poderia se afirmar em relação a selvagens representantes de raças nobres (escravos negros), a quem se tortura com degradantes castigos? Além disso, se a guerra, flagelo infernal cuja existência deve ser banida dentre todos os povos civilizados, pode ser de alguma forma desculpada, é preciso ser feita para livrar a nossa terra dos tiranos invasores que se fizeram soberanos. A Itália gemeu, não por dias, meses ou anos, mas durante séculos, sob o jugo despótico de todo tipo de dominadores. Sua guerra, pois, é desculpável e até mesmo justa, (...) A Itália ressurgiu em virtude de seus bravos filhos terem escapado das pesadas cadeias com que foram acorrentados por seus tiranos. A espoliada mãe pátria, olhando para seus nobres filhos secularmente divididos e escravizados pelo despotismo ambicioso de usurpadores estrangeiros, recobrou finalmente a liberdade e, da mesma forma, seus direitos. (pp.317-318) Translated by Matheus Iglessias Mazzochi -MM

0 Comments

[Originally published on Facebook March 17, 2021]

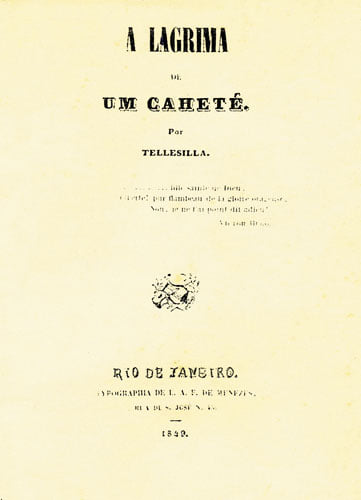

Today I bring three fragments from Nísia’s poem A Lágrima de um Caeté (Tear of a Caeté). The poem was published in 1849 in Rio de Janeiro, the same year that Revolução Praieira [1] ended. In it, Nísia sings for the oppressed First Natives, who were pictured by Romanticist Brazilian poets as willingly accepting colonization. Clearly, Nísia disagrees with that image. Because of the political instability of that time, and due to the violent resolution of Revolução Praieira by Brazilian Empire [2], there is a parallel between the government that oppressed the First Natives and the government that oppressed the liberals. The poem had two editions (both from 1849) and Nísia signs it as “Tellesilla”, an ancient Greek poet from Argos who was against oppression. “First Natives of Brazil, what are you? Savages? You don’t enjoy your goods anymore… Civilized? No… Your caring tyrants Keep you away from such weapons that have been hurting you Poor Cablocos! You don’t have any degree!... You lost everything, Except the infamous title of coward… * The Caetes’ venerated spirits are avenged! Sadly abandoned, without land, without goods, Blindly following your master’s voice You have lost your purity and traditions. * From Amazonas to Prata, The people are crying: - Enough, terrible monster, Your empire is crumbling! But you, my poor Caete, Listens to the Truth: Go seek the forests, only there You will be free. What do you make of these passages? To me, they are about the loss of identity of a people due to oppression. The “First Natives of Brazil” have lost “everything”. They cannot say who they are, and if they do, it doesn’t matter anymore. Just like the enslaved people. Also, they “have lost their traditions”. The Europeans call them “savage” when they are living in the forests. When they are not, after being brought to the cities and have lost their “purity”, they are called “coward”. Europeans and Brazilians call themselves “civilized” because they fulfill conditions of a “civilized” culture, conditions not created and not consented to by either the First Natives or the enslaved people. In this poem, Nísia avenges the First Natives, the Caetes. She does so to ensure they are not to be forgotten. However, the oppression that took their freedom and identity happens among the same people. The “Empire is crumbling”, Nísia says, and such proposition can be heard from North to South of Brazil (Amazonas River to Prata River). Thus, it seems that she is saying that the same government that oppresses the First Natives and the enslaved people is oppressing its own people. ____ [1] The Revolução Praieira was one of the many revolutions that were happening during the Brazilian Empire (1822-1889). Want to know more? Here is a reliable link that can be translated by Google about the Revolução Praieira: https://brasilescola.uol.com.br/.../revolucao-praieira.htm [2] Dom Pedro I proclaimed the Brazilian independence on September 7th, 1822. The country became an Empire until November 15th, 1889, when a military coup by Marshal Manuel Deodoro da Fonseca happened, making Brazil a republic. Here is a good link from Encyclopaedia Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/place/Brazil/Independence ----- Indígenas do Brasil, o que sois vós? Selvagens? os seus bens já não gozais... Civilizados? não... vossos tiranos Cuidosos vos conservam bem distantes Dessas armas com que ferido tem-vos De sua ilustração, pobres Cablocos! Nenhum grau possuís!... Perdeste tudo, Exceto de covarde o nome infame... * Dos Caetés os manes vingados estão! Em triste abandono, sem Pátria, sem bens, Às cegas seguindo a voz de um senhor Pureza e costumes perdido tu tens!... * [...] Do Amazonas ao Prata O povo lhe está bradando: - Sacia-te monstro atroz, Teu império está finando! Mas tu meu pobre Caeté Escuta a Realidade; Busca as matas, lá somente Gozarás da Liberdade Passages retrieved from: A Lágrima de um Caeté / Nísia Floresta Brasileira Augusta; Org. Constância Lima Duarte. 4. ed. Natal: 1997. 66p. Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN): https://www.bing.com/search... Translated by Matheus Iglessias Mazzochi Picture from http://www.projetomemoria.art.br/NisiaFl.../popups/044b.html -MM [Originally published on Facebook March 12, 2021]

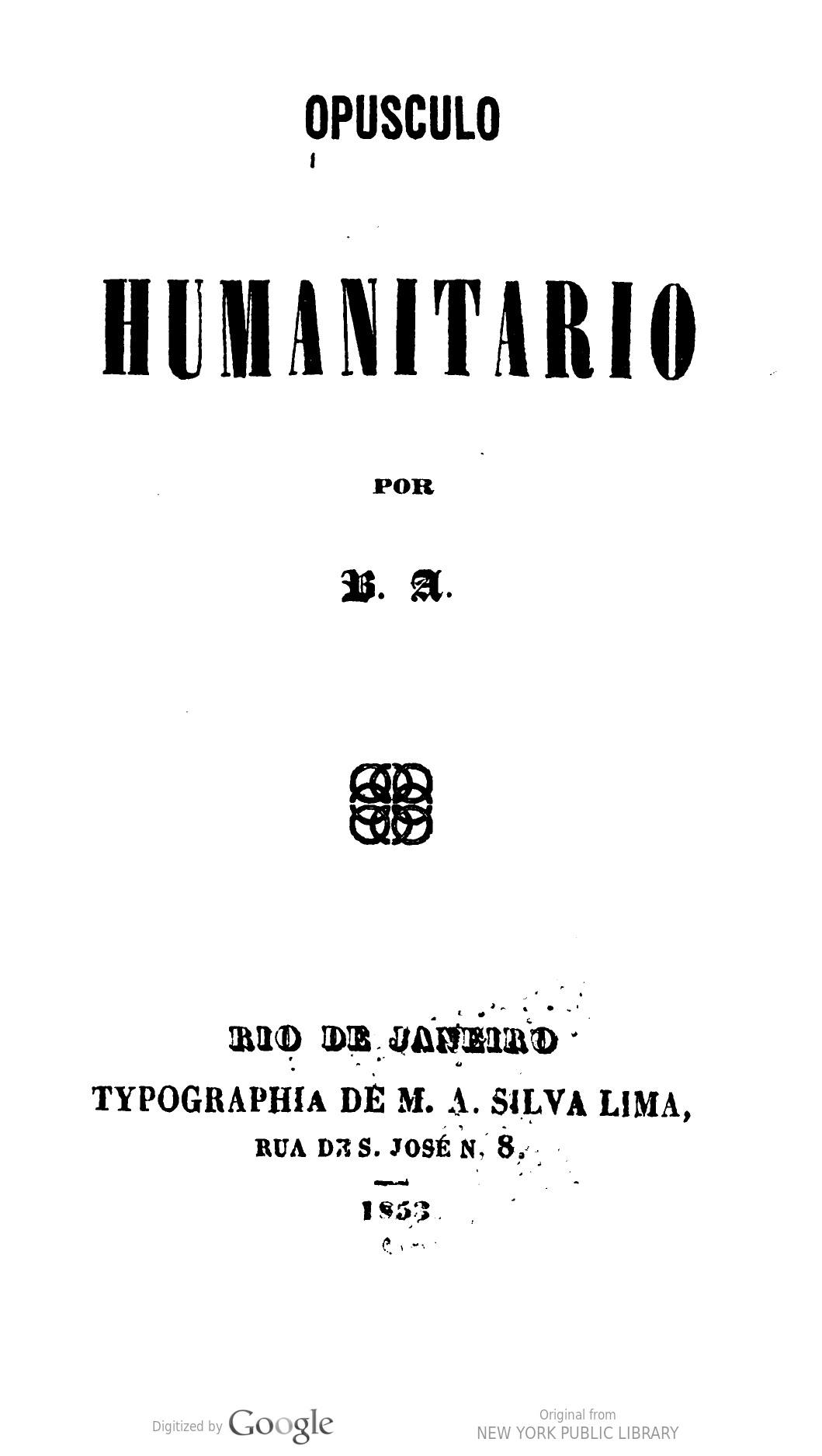

Our first post about Nísia Floresta is from Opúsculo Humanitário, a book she published in 1853 in Rio de Janeiro. In it, Nísia famously argues that society’s progress can only be evaluated by how important women are in it. Although Nísia criticizes (the lack of) women’s education in Brazil in her book, she also talks about slavery. A link to the book is available in the end of this post as well as the original passage (in Portuguese). Chapter XLII (pp. 103-104) “Having all housekeeping being done by slaves, the girl finds herself surrounded by pernicious lessons since her first infancy. She observes behaviours and listens to words of such unfortunate race (people?), which is demoralized by captivity and condemned by the whip. Her sensibility gradually becomes familiar with such distressing show, which repeats almost daily in front of her; it is not rare to see her (with horror we say) inflicting the cruelest treatment to her own wet nurse who breastfed her and is indifferently sold or rented as a useless burden. Such revolting ingratitude is one of the most despicable examples given to that girl, who will become a mother one day and will pass that to her own children! (...) Thus, that sprout of intelligence embedded in her grace develops under the most contrary conditions to its future fulfillment. And no one is mindful that childhood is receiving unfavorable impressions from such art, and as Homer said, it is recorded in the soul as is in a wax table, where all the traits are more or less distinct; impressions that, like a subtle poison, destroys her best natural dispositions.” One of the interesting things implied in this passage is the negative consequences of slavery to human’s development. Since slavery happens at home, “almost daily”, girls are “surrounded by pernicious lessons”. They learn through examples by observing how the slaved person is treated and by listening to the words spoken. Consequently, they learn how to treat other human beings. That is not good. Such education, “by the whip” as Nísia says, “destroys” our “best natural dispositions”, which seems to be the human sensibility. Worse than that, the child becomes ungrateful, apathetic to the woman who breastfed her by growing in such distressing environment. Breastfeeding is one of the first bond that a mother creates to her child. It is a primary human bond. In the end, slavery reduces that human bond to a thing that can be sold or rented. ____ Link to the passage: (https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433075997266...) Todo o serviço do interior das famílias sendo feito entre nós por escravos, a menina acha-se desde a primeira infância cercada de outras tantas perniciosas lições, quantas são as ocasiões em que observa os gestos, as palavras e os atos dessa infeliz raça, desmoralizada pelo cativeiro, e condenada à educação do chicote! Sua nascente sensibilidade se habitua gradualmente a esse espetáculo afligidor, repetido quase diariamente a sua vista; não é raro ver ela (com horror o dizemos) infringir o mais cruel tratamento à própria ama que a amamentou, a qual é alguma vez indiferentemente vendida ou alugada como um fardo inútil, apenas acaba de ser-lhe necessária! Esta revoltante ingratidão é um dos mais detestáveis exemplos dados à menina, que tendo um dia de ser mãe, o transmite por seu turno a seus filhos! (...) Assim, aquele embrião de inteligência envolvido na epiderme de uma graça factícia desenvolve-se nas condições mais contrárias ao seu futuro engrandecimento. E ninguém atenta para as desfavoráveis impressões que de esta arte vai a infância recebendo, e gravando na cera, que conforme a expressão de Homero tem-se na alma, onde se conservam com traços mais ou menos distintos; impressões que semelhante a sutil veneno lhe destroem por vezes as melhores disposições naturais. -MM |

Authors

Jacinta Shrimpton is a PhD student in Philosophy at the University of Sydney. She is co-producer of the ENN New Voices podcast Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed