|

In this episode, Olivia Branscum speaks with Nic Bommarito, Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Simon Fraser University. We discuss the French philosopher Simone Weil (1909-1943), focusing especially on what she has to teach us about the moral value of attention and the true uses of education. Nic and I also talk about his work in Tibetan Buddhist thought and his experiences studying figures and traditions that have been excluded from mainstream histories of philosophy.

Further Reading Primary Texts (by Simone Weil) “Reflections on the Right Use of School Studies with a View to the Love of God” (written c. 1942, published in Waiting for God) La Pesanteur et la Grâce (available in English translation as Gravity and Grace) (1947) L'enracinement : Prélude à une déclaration des devoirs envers l'être humain (available in English translation as The Need for Roots) (1949) Attente de Dieu (available in English Translation as Waiting for God) (1950) Secondary Texts “Private Solidarity” by Nicolas Bommarito (2015) nner Virtue by Nicolas Bommarito (Oxford University Press, 2018) Seeing Clearly: A Buddhist Guide to Life by Nicolas Bommarito (Oxford University Press, 2020) To listen to this episode, please visit our podcast page.

0 Comments

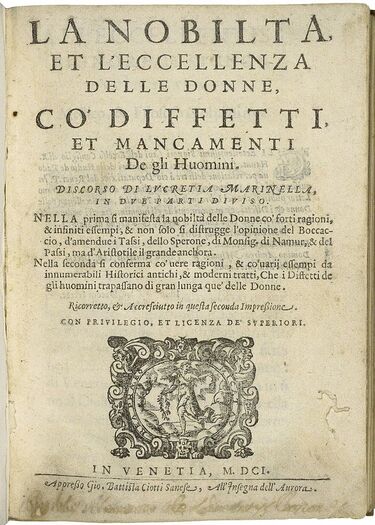

In reading chapter III of The Nobility and Excellence of Women and the Defects and Vices of Men, I am most interested in Marinella’s appeal to the philosophies of Aristotle and Plato in establishing her bold feminism. Marinella argues that the natural beauty of women reveals the divine excellence of their souls. She writes:  So if women are more beautiful than men, who, as can be seen, are generally coarse and ill-formed, who can deny that they are more remarkable? Nobody, in my opinion. Thus it can be said that beauty in a woman is a marvelous spectacle and a miracle worthy of respect, though it is never fully honored and respected by men. But I wish to go further and show that men are obliged and forced to love women, and that women are not obliged to love them back, except merely from courtesy. I also wish to demonstrate that the beauty of women is the way by which men, who are moderate creatures, are able to raise themselves to the knowledge and contemplation of the divine essence. (62) Marinella first argues that women’s being naturally more beautiful than men reveals the superiority of their souls. She writes, “The greater nobility and worthiness of a woman’s body is shown by its delicacy, its complexion, and its temperate nature, as well as by its beauty, which is a grace or splendor proceeding from the soul as well as from the body” (57). In order to argue that one’s bodily appearance mirrors the state of one’s soul, Marinella appeals to the idea of the hylomorphism found in Aristotle where the soul is the form of the body and body is the matter of the soul. She asks, “What is the form of the body if not the soul? The greatest poets teach us clearly that the soul shines out of the body as the rays of sun shine through transparent glass” (57). The soul, acting as the form of the body, serves as a template for the appearance of the body and, in its bodily existence, reveals the true nature of the being. The more beautiful a woman’s body is, then, according to Marinella, the more beautiful her soul will be. In comparison to women, however, “all men are ugly” and therefore, inferior in their souls (63). With Platonism in mind, Marinella argues that the origin and cause of the external beauty of women is God. God uses the forms, such as beauty, to fashion the external world in the most perfect way. Marinella describes God as “the minister who takes [beauty] … from every other source of perfection and excellence” in order “to create this rich and esteemed treasure house of beauty” (62). Corporeal beauty, then, is personally bestowed by God onto only the worthy creatures of the world (59). Great beauty, like that seen in the bodies of women, reveals a divine nobility and excellence in the being. She writes, “Each writer, Platonist, and poet affirms that beauty comes from God… Divine beauty is, therefore, the first and principal cause of women’s beauty, after which come the stars, heavens, nature, love, and the elements” (60). Like other beauties in the external world, the beauty of women stems from God. Men, however, do not have this beauty. This disparity, according to Marinella, shows that men are less worthy beings than women who are chosen to embody a divine form such as beauty. Most interestingly, Marinella concludes that if women are more beautiful than men, and if this beauty originates in God, then men are obligated to love and contemplate the beauty of women because it will lead them to knowledge of God. She asks, “What poet is there, however coarse, who does not state openly that beauty is the path that guides us directly to the contemplation of divine wisdom…beauty, not being earthly but divine and celestial, always raises us toward God, from whom it is derived” (66). Marinella’s argument here positions women as invaluable gateways to God and beauty itself. In this way, women, by their very nature, demand worship and love while men do not. Nodding to Homer, Marinella describes this phenomena as a “golden chain” (66). Similar to Diotima’s Ladder of Love, found in Plato’s Symposium, Marinella describes our love for physical beauty as a way of ascension to higher forms of beauty. First, we see “corporeal beauty” which is “gazed at and considered by the mind, through the means of the outer eye” (66). In admiration of this beauty, we “ascend” and look “with the internal eye at the soul that, adorned with celestial excellence, gives form to the beautiful body” (66). In contemplation of the soul, we consider the “angelic spirits” and “this contemplative mind seats itself within great light… of the one who supports the chain” (66). In appreciating corporeal beauty, we are led to “delight in Him” and are “made happy and blessed” (66). Men, then are obligated to contemplate the beauty of women because they will be naturally led to a contemplation of the divine. Marinella defends the superiority of women with an appeal to Aristotle’s hylomorphism, Plato’s forms, and by arguing that their bodily beauty reflects their beautiful souls which lead men to knowledge of God. --MP Text source: The Nobility and Excellence of Women, and the Defects and Vices of Men. Edited and translated by Anne Dunhill, The University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Image info: The title page of Lucrezia Marinella's La nobilita, et l’eccellenza delle donne. Published in Venice 1601. Source: http://luna.folger.edu/luna/servlet/s/184k1c Towards the end of the second day of Fonte’s Worth of Women, she defends the beauty of the mind and spirit as superior to the beauty of the body:

Although Fonte ultimately concludes that the mind and spirit are superior to the body in quality and beauty, she does not deny the merit of a beautiful body and begins by highlighting the benefits of our corporeal form. The value of the body, according to Fonte, comes from its power to inspire an initial “love” and “desire” for one another. When we meet another person, the appearance of their body “is the first to present itself to our eye and our understanding.” Given our limited perspective, we are directed by our physical desires in our first evaluation of potential lovers. Fonte acknowledges the great influence of a beautiful appearance as she writes, “You’re quite right when you say that in the short term what we see and what pleases the eye has far more power over us than what we cannot see or grasp in an instant” (207). The power of the corporal form to attract, according to Fonte, is greater than the power of the invisible mind and spirit. Yet, this same power leads lovers to desire a fragile, mortal, and inferior kind of beauty.

Unlike the body, Fonte argues, the mind and spirit are truly worthy of our love. Not only do the mind and spirit “[reside] in a nobler part of us,” their very quality exceeds that of our corporeal form. The beauty of the mind and spirit, Fonte argues, “are the kind of beauties that do not fade or wither, but last our whole lives and even live on after our deaths, in our fame” (207). Their ability to withstand the costs of time make the mind and spirit superior to “corporeal beauty” which is “like a fragile flower…fall wilted and dry to the earth.” While the body always falls subject to “illness…fatigue or gradual aging,” inevitably losing its beauty, the beauty of the mind and spirit persists in the face of adversity and escapes the ugly consequences. The superiority of the mind and spirit, then, comes from their infinite beauty which cannot be damaged or lost. Most interestingly, Fonte highlights the moral dimension of the mind and spirit. She describes their beauty as “virtue in its various forms” with “glories” that even the poets cannot capture. In this way, the mind and spirit have an innate and “divine” worth in their nature. Fonte also argues that the mind and spirit “belong” to us in a way our bodies do not. While our bodies change and lose their beauty as we age or fall ill, the beauty of our mind and spirit “inalienably belongs to us”. For being impervious to change and having a moral nature, the mind and spirit are of “a nobler quality” in comparison to the body. It is important to note that the mind and spirit are not entirely separate from the body in love. The value of the body exists within its power to ignite a carnal attraction in the mind. However, overall, the body’s vulnerability and volatility makes it inferior to the impenetrable mind and spirit. For these reasons, Fonte concludes that the lover who desires their beloved for their bodily attributes ignores “what is more important in us and more worthy” of being a reason for love: the beautiful, superior, and “immortal” spirit and mind. --MP Text source: The Worth of Women: Wherein Is Clearly Revealed Their Nobility and Superiority to Men. Edited and Translated by Virginia Cox, The University of Chicago Press, 1997. Image info: Blessed Soul, illustrated by Guido Reni, Italian, published between 1640 and 1642 https://artvee.com/dl/blessed-soul On the second day of the dialogue, Fonte explicitly argues that women should receive an education. She writes,

Fonte claims two things here: first, that receiving an education leads to a virtuous life and second, that in withholding education from women, men commit both an ethical and epistemic injustice. With the former claim, Fonte works to rebut the belief held by men that says an educated woman becomes immoral. She argues that, in reality, without an education, “an ignorant person is far more liable to fall into err.” Fonte defends this argument by depicting the common undesirable and uneducated women. These women, such as the “illiterate maid servants,” the “peasant girls and plebeian women,” fold to their sexual desires and easily “give in to their lovers.” Without the opportunity to exercise their minds through reading and writing, these women become “gullible” to the persuasions of men and cannot defend themselves. According to Fonte, uneducated women lack the ability to reason and as a result, must depend on the word and direction of men. Of course, even educated women are subject to the “pricking of the senses,” but their intellect allows them to combat physical temptation. For Fonte, education is just “the pursuit of virtue.” Without schooling, then, women do not have the resources to become virtuous and as a result, they inevitably give into sexual relations.

Fonte’s argument highlights the way in which men have been counterproductive and ineffective in trying to make women more virtuous. Instead of providing them with the necessary tools to defend themselves against lustful desires, men leave them weak and vulnerable. Notice that Fonte does not argue against the belief that women are naturally perverse or driven by their bodily appetites. Instead, she uses this idea as a reason in favor of giving women an education. In this way, Fonte appeals to the beliefs of men. Still, she reveals how, in the name of keeping women from their natural vices, men have inhibited women from achieving a moral life. Fonte presents the characters in her dialogue as exemplary of the benefits of educating women. It is because these women “have read [their] cautionary tales and learnt [their] moral lessons” that they “developed a love for virtue.” Readers of the dialogue, then, can look to Fonte’s characters as proof that education and virtue go hand in hand. In this passage, Fonte argues that a woman can only fight her sexual inclinations through education and that men have wrongfully repressed women who wish to pursue virtue. --MP Image info: The Education of the Virgin Mary, illustrated by Giovanni Francesco Romanelli, Italian, published in Rome in 1630. Text source: The Worth of Women: Wherein Is Clearly Revealed Their Nobility and Superiority to Men. Edited and Translated by Virginia Cox, The University of Chicago Press, 1997. I will first look at Franco’s poem, Capitolo 24. Franco wrote this poem as a response to a man who had insulted and threatened another woman, presumably a fellow courtesan. The entire poem is 160 lines. I will examine lines 70-90 as seen below:

Earlier in the poem, Franco argues that virtue lies in the soul and mind and that women “have given/ more than one sign of being greater than men” in this way (65-66). In the excerpt above, Franco outlines the ways in which women show their superiority in virtue. Franco seems to make two arguments here: first, that submission to men serves as an act of virtue and second, that childbearing plays a significant role in both submission and in improving the condition of the world. Through their submission and childbearing, Franco argues, women are superior to men in virtue.

Franco describes the submission of women as an adaptive response to the weakness of men. Women must guide and carry men because men are weak and prone to “fall” without women’s support. Franco implies that because men “do wrong,” they cannot support the weak in the same way women support men. As a result, women must become the submissive party if they want to “avoid pursuing wrongdoing.” Submission is thus a choice women make in order to compensate for the shortcomings of men. Still, Franco reminds the man whom the poem addresses that, if women were to ignore this call to service and reveal their superiority, women would easily “surpass” men. Yet, a woman intentionally “submits to tyrannical, wicked man” and becomes “silent.” The submission of women, for Franco, acts as both a virtue and a reflection of the strength women have in comparison to men. Childbearing, for Franco, exemplifies the virtuous and indispensable submission of women. An end to the submission of women, according to Franco, directly results in an end to childbearing. Franco presents childbearing as a paradigm act of submission. Yet, in providing offspring, women have the unique ability to play a role in improving the condition of the world. For Franco, women bear children so that women do not “ruin the world” and instead, make the world “beautiful.” In this way, submission can be said to empower women as they are able to affect the world in a significant and unique manner by giving birth. For Franco, childbearing embodies the powerful sacrifice women make in order to improve the condition of the world. This submission is also voluntary and actively chosen as a result of the superior reason and morality of women. In the excerpt above, Franco tells the story of why men became the dominate sex. According to Franco, the power of men results directly from the grace and selflessness of women who are wiser and superior in virtue. In order to compensate for the failures of the weaker sex, women submit and support men. The power given to men, however, can be taken back at any time if women refuse to procreate. Yet, their virtuous and reasonable nature leads them to do what is best for the world as a whole and bring the beauty of offspring into the world. The submission of women to men, seen especially in childbearing, exemplifies the virtue and reason of women as they refrain from revealing their true superiority to better serve the world. [Originally published on Facebook 30 April 2021]

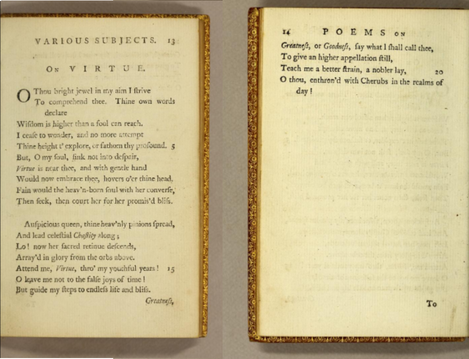

Our third and last poem is called, “On Virtue”, and it also belongs to Phillis’ poetry collection entitled, “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral” that was published in 1773. As always, a link to the digitized version is provided at the end of this post. Enjoy the poem: O thou bright jewel in my aim I strive To comprehend thee. Thine own words declare Wisdom is higher than a fool can reach. I cease to wonder, and no more attempt Thine height t’explore, or fathom thy profound. But, O my soul, sink not into despair, Virtue is near thee, and with gentle hand Would now embrace thee, hovers o’er thine head. Fain would the heaven-born soul with her converse, Then seek, then court her for her promised bliss. Auspicious queen, thine heavenly pinions spread, And lead celestial Chastity along; Lo! now her sacred retinue descends, Arrayed in glory from the orbs above. Attend me, Virtue, thro’ my youthful years! O leave me not to the false joys of time! But guide my steps to endless life and bliss. Greatness, or Goodness, say what I shall call thee, To give a higher appellation still, Teach me a better strain, a nobler lay, O Thou, enthroned with Cherubs in the realms of day! Here, it seems that Virtue and Wisdom are related, and that Virtue is a means to Wisdom. Ordinary people (the “fool”) cannot reach Wisdom because Wisdom is too high. This could make us “to cease to wonder, and no more attempt/ Thine height t’explore, or fathom thy profound”. What is left for us besides having our soul sinking “into despair”? Virtue. Virtue can not only save us from despair, but also it can serve as a guide to “endless life” and “promised bliss”. In other words, Wheatley is suggesting that Wisdom is not reached directly, but through Virtue. Thus, rather than seeking to be a wise person, she thinks we should seek to become a virtuous person first. Now, what do you make of “Teach me a better strain”? To me, Wheatley is talking about two things: what is seen and what is not. The colour of our skin is something that is seen; a virtuous soul is something that is not. It would not matter the colour of someone’s skin, for instance, but only whether that person is virtuous. Digitized Version [Internet Archive]: https://archive.org/.../poemsonvarioussu.../page/13/mode/1up -MM |

Authors

Jacinta Shrimpton is a PhD student in Philosophy at the University of Sydney. She is co-producer of the ENN New Voices podcast Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed