|

In this episode, Olivia Branscum speaks with Nastassja Pugliese, Assistant Professor of Philosophy at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. We talk about the life, work, and reception of the nineteenth-century Brazilian philosopher, Nísia Floresta Brasileira Augusta (born Dionísia Gonçalves Pinto in 1810). Nastassja and I talk about Nísia’s philosophy of education, her enlightenment critique of slavery and colonialism, and the common misconception that Nísia translated the work of Mary Wollstonecraft. Though only one of Nísia’s essays has been translated into English, listeners can find some of her writings in French and Italian, and should keep an eye out for Nastassja’s forthcoming introduction to Nísia with Cambridge University Press. Further Reading Primary Texts By Nísia Floresta: Direitos das mulheres e injustiça dos homens (Women's rights and injustice of men), 1832 Páginas de uma vida obscura (Pages of a dark life), 1855 Opúsculo humanitário (Humanitarian brochure), 1853 A lágrima de um Caeté (The tear of a caeté), 1847 “Woman,” translated by Livia A. de Faria in 1865 By others: Woman not inferior to man, or, A short and modest vindication of the natural right of the fair-sex to a perfect equality of power, dignity, and esteem, with the men, by the anonymous “Sofia/Sophia,” 1739 Woman’s superior excellence over man, or, A reply to the author of a late treatise entitled, Man superior to woman…, by the anonymous “Sofia/Sophia,” 1740 The Woman as Good as the Man: Or, The Equality of Both Sexes, by Poulain de la Barre, trans. A. L., London: N. Brooks., 1677 Secondary Texts Gender, Race and Patriotism in the Works of Nísia Floresta, by Charlotte Hammond Matthews “Overthrowing the Floresta-Wollstonecraft Myth for Latin American Feminism,” by Eileen Hunt Botting and Charlotte Hammond Matthews Nísia Floresta, by Nastassja Pugliese, under contract with Cambridge University Press (2023)

0 Comments

In this episode, Haley Brennan talks with Alison Stone, professor in the Department of Politics, Philosophy and Religion at Lancaster University. We discuss the work of British women philosophers of the 19th century, including Frances Power Cobbe, Ada Lovelace, and Harriet Martineau. We cover a range of topics that these philosophers worked on, including animal rights, feminism, ethics, and philosophy of mind. In addition to these topics, we talk about the correspondence that these women had with each other, the influence they had on political movements in 19thc Britain, and where and how to look to find the philosophical writings of women in the period. We also discuss the way that perceived philosophical importance and impact varies across time and place, and how this affects which philosophers we research and teach today.

Works by British Women Philosophers Mentioned in the Episode Unless otherwise specified, all works listed are in the public domain and are available online Frances Power Cobbe, ‘The Rights of Man and the Claims of Brutes’ —, An Essay on Intuitive Morals —, Darwinism in Morals --, ‘Wife-Torture in England’ —, Essays on the Pursuits of Women, with a paper on Female Education —, ‘Why Women Desire the Franchise’ Ada Augusta Lovelace, ‘Sketch of the Analytical Engine’ Harriet Martineau, Illustrations of Political Economy --, ‘Letters on Mesmerism’ —, Autobiography —, with Henry George Atkinson, Letters on the Laws of Man’s Nature and Development Victoria Welby, Signifying and Understanding, ed. Susan Petrilli (De Gruyter, 2009) Further Reading Alison Stone, ed., Frances Power Cobbe: Essential Writings of a Nineteenth-Century Feminist Philosophy (Oxford University Press, forthcoming early 2022) Charlotte Alderwick and Alison Stone, ed., Nineteenth-Century Women Philosophers in Britain and America, British Journal for the History of Philosophy 29, no. 2 (2021) In this episode, Haley Brennan talks with Dalia Nassar, senior lecturer in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Sydney. We discuss the works of several German women philosophers in the late 18th and 19th centuries, including Germaine de Staël, Rosa Luxemburg, and Karoline von Günderrode. The women we discuss wrote on a wide range of topics: idealism, phenomenology, feminism, labour movements, workers’ rights, socialism, and environmental ethics. In addition to these topics, we talk about why it is that these women, who published and were discussed in their own time, have not received modern philosophical attention, the accessibility of their philosophical writings, the importance of being aware of the full range of philosophers writing and corresponding in Germany in the 19th century, and the variety of benefits that come from including the works of these philosophers in classes on German philosophy in the 19th century. We also talk about the value of being flexible and open about what counts as philosophical question, and the ways that philosophy can be applicable to real-world issues.

To listen to this episode, please visit our podcast page. Works by German Women Philosophers Mentioned in the Episode Unless otherwise specified, all works listed are in the public domain and are available in the original language and (often) in English translation online. Germaine de Staël, De l’Allemange (On Germany). Bettina Brentano von Arnim, Die Günderrode. ——, Armenbuch (The Book of the Poor). Margaret Fuller, “Bettina Brentano and her friend Günderrode.” The Dial Vol VII. Clara Zetkin, “In Defence of Rosa Luxemburg.” ——, “Social-Democracy and Women’s Suffrage.” Karoline von Günderrode, “The Idea of the Earth.” Available in English in Women Philosophers in the Long Nineteenth Century: The German Tradition, edited by Dalia Nassar and Kristin Gjesdal. Rosa Luxemburg, “Wage Labour.” Available in English in Women Philosophers in the Long Nineteenth Century: The German Tradition, edited by Dalia Nassar and Kristin Gjesdal. Hedwig Dohm, “Nietzsche and Women.” Available in English in Women Philosophers in the Long Nineteenth Century: The German Tradition, edited by Dalia Nassar and Kristin Gjesdal. Other Works Mentioned Hegel, Lectures on the History of Philosophy. Copleston, A History of Philosophy. Further Reading Women Philosophers in the Long Nineteenth Century: The German Tradition, edited by Dalia Nassar and Kristin Gjesdal, New York: Oxford University Press, 2021. Nassar, Dalia. “The Human Vocation and the Question of the Earth: Karoline von Günderrode’s Philosophy of Nature.” Archiv für Geschichte der Philosophie 20, 2021. [Originally published on Facebook March 31, 2021]

Our last post on Nísia Floresta is from Opúsculo Humanitário, which is the same book from our first post, and is about women’s education. Here is the passage: XXVI (p.59 of the book; 69 of the digitized version) “The more ignorant a nation is, the easier it is for an absolute government to exercise its unlimited power over it. It is from that principle, so contrary to the progressive march of civilization, that most men are against making easier how women cultivate their spirit. However, this is a mistake that has been and always will be contrary to the prosperity of nations as well as is contrary to the domestic fortune of men. (…) Just as a paternal government is the most proper one to make people happy, and a properly cultivated intelligence of those nations is the best incentive for them to fulfill their duties, so too is moral education the safest guide to women. It is the pole star that indicates their north, in the fragile struggle in which they have to navigate as a ship in the sea, a sea seeded with abrolhos (pointed coral reefs), which is called life. The lack of a good education is the primary cause that contributes to women to lose their north, which is nothing else but morality, in the midst of the corruption of society. Always seeking to hold their intelligence, to weaken their senses, they make women unable to occupy, as they should to begin with, the care of purifying their heart; women would never advantageously achieve such thing if their intelligence remains without culture.” As we have seen, Nísia Floresta was against slavery because it is a form of oppression of one people over another. Such oppression can be instantiated in many varieties: it can manifest on basis of color (Europeans to Africans), political views (Italian liberals versus their government and Brazilian liberals versus the Empire), or culture (colonization over the First Natives). This passage shows us that Nísia thinks that lack of education could be another instantiation of oppression because it willingly hinders the moral development of human beings. Since men were “against making easier” for women to learn, men were willingly hindering women’s moral development. Therefore, men were oppressing women. Thus, Nísia finds a common ground between colonized First Natives, enslaved people and women: they were all devoid of education. Worse than that, they were deprived of education by the oppressor, whoever it be. Further, Nísia compares the political influence of an absolute government over an ignorant nation to the power of men over women. Such comparison allows us to consider despotic governments as oppressors too. Thus, we may say that Nísia was against a universal form of oppression, a form that can be instantiated differently. If such oppression is justified by color, we call Nísia an abolitionist; if it is justified by sex, we call her a feminist, and so forth… However, I cannot make something of “a paternal government is the most proper one to make people happy”. She seems to be listing kinds of “guides”. Moral education is “the safest guide” for women. Cultivated intelligence is “the safest guide” for a nation that seeks the fulfilment of its duties. A paternal government is “the safest guide” to make people happy. Was she defending paternal governments or was she just saying that it does not matter how bad a ruler is, if the ruler rules paternally, then the people will not care? If the latter, she may have said that ironically, criticizing paternal governments. __ Retrieved from: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433075997266... Original in Portuguese: “Quanto mais ignorante é um povo, tanto mais fácil é a um governo absoluto exercer sobre ele o seu ilimitado poder. É partindo deste princípio, tão contrário à marcha progressiva da civilização, que a maior parte dos homens se opõem a que se facilite à mulher os meios de cultivar o seu espírito. Porém, é este um erro, que foi e será sempre funesto à prosperidade das nações, como à ventura doméstica do homem. (...) Assim como um governo paternal é o mais próprio a fazer a felicidades dos povos, e a inteligência destes devidamente cultivada o melhor incentivo para o exato cumprimento de seus deveres; assim também a educação moral é o guia mais seguro da mulher, a estrela polar que lhe indica o norte, no frágil batel em que ela tem de navegar por esse mar semeado de abrolhos, a que se chama vida. A falta de uma boa educação é a causa capital, que contribui para que a mulher, no meio da corrupção da sociedade perca esse Norte, o qual não é outro mais que a moral. Procurando-se sempre prender-lhe a inteligência, enfraquecer-lhe os sentidos, inabilitam-na para ocupar-se, como devia, antes de tudo do cuidado de purificar o seu coração; o que nunca poderá ela vantajosamente conseguir se a sua inteligência permanecer sem cultura.” Translated by Matheus Iglessias Mazzochi -MM [Originally posted on Facebook March 24, 2021.]

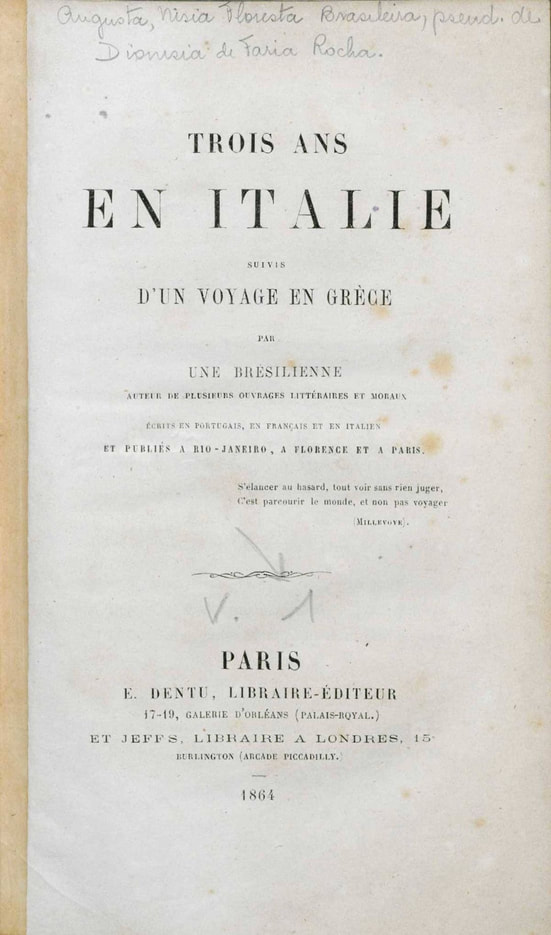

Our fourth post on Nísia Floresta is from “Trois ans en Italie: suivis d’un voyage en Gréce” (Three years in Italy followed by a trip to Greece). This book was published in 1864 in France, but only was translated into Portuguese in 1998. The book is not only a journal of her trips throughout Italy and Greece, full of descriptions of the landscapes and architecture; it is an analysis of the history and political development of those nations. In it, Nísia foresees the Italian Unification [1]. Here is an interesting passage: “If such rebellions [2] were never to be excusable, (…) could the same be said about the savage representatives of noble races (the black enslaved), whom are tortured with humiliating punishments? Furthermore, if war, this infernal scourge whose existence must be banned among all civilized people, can be somehow excused, then it must be done to free our land against the tyrant invaders whom claimed themselves sovereigns. Italy has been tormented, not for days, months, or years, but for centuries, by the despotic yoke of all kinds of conquerors. Its war, therefore, is excusable and even just (…) Italy has risen because its brave sons escaped from the heavy prisons in which they were chained by their tyrants. The spoiled motherland, looking at its noble sons, divided and enslaved by the ambitious despotism of foreign usurpers, finally regained freedom and, likewise, its rights” (pp.317-318). This is a subtle passage. If the Italian rebellions are not excusable for fighting against oppression and for the right to be free, then the same could be said to any rebellion by “the savage representatives of noble races”. But we do consider the Italian rebellions excusable. So, we must consider as excusable any rebellion made by the “noble races”. And by “noble races” Nísia means the black enslaved. It is a powerful analogy and it is logically valid (it is a Modus Tollens). She goes on to state the reasons of the Italian rebellions, leaving us to continue her analogy. Their rebellions are excusable because they fight against “tyrant invaders whom claimed themselves sovereigns”. This is a just cause for Nísia. The Italians were enslaved by “ambitious despotism of foreign usurpers” and they just seek freedom and rights. Is not that what happened in Africa with the African people? Since both Italians and Africans share the same burden of slavery by foreigners and the claim for freedom, to advocate for the Italian unification would be to advocate against slavery. Here, “slavery” is meant in the broad sense: of one nation over another. Thus, it does not reference the color, the language, or the culture of the nation. If one nation is oppressing, enslaving another, it is not right. Thus, any rebellion that claims freedom and rights is excusable and justified. In one single passage, Nísia praises the Italian unification and defends abolitionism. ----- Retrieved from: https://memoria.ifrn.edu.br/.../Tr%c3%aas%20anos%20na... Original in French: 1st Volume: http://objdigital.bn.br/.../drg291826/drg291826.html... 2nd Volume: http://objdigital.bn.br/.../drg1414580/drg1414580.html... [1] Also known as “Risorgimento” (Resurgence), the Italian Unification was the historical process which unified Italian kingdoms into one, resulting the Kingdom of Italy in March 17th, 1861. It was a consequence of the ideas of French revolution that were brought by Napoleon’s troop to Italy when he was at war with Austria. Here is a good article of Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/place/Italy/Unification [2] Here Nísia is referring to the many rebellions that were emerging in Italy prior to its unification. She explains them in previous pages. Although King Francisco II defeated Garibaldi’s troops in Naples, Garibaldi himself won battles against General Landi in Sicily, such as the battle of Calatafimi, and in Munrriali. * Se a revolta jamais fosse desculpável, (...) o mesmo poderia se afirmar em relação a selvagens representantes de raças nobres (escravos negros), a quem se tortura com degradantes castigos? Além disso, se a guerra, flagelo infernal cuja existência deve ser banida dentre todos os povos civilizados, pode ser de alguma forma desculpada, é preciso ser feita para livrar a nossa terra dos tiranos invasores que se fizeram soberanos. A Itália gemeu, não por dias, meses ou anos, mas durante séculos, sob o jugo despótico de todo tipo de dominadores. Sua guerra, pois, é desculpável e até mesmo justa, (...) A Itália ressurgiu em virtude de seus bravos filhos terem escapado das pesadas cadeias com que foram acorrentados por seus tiranos. A espoliada mãe pátria, olhando para seus nobres filhos secularmente divididos e escravizados pelo despotismo ambicioso de usurpadores estrangeiros, recobrou finalmente a liberdade e, da mesma forma, seus direitos. (pp.317-318) Translated by Matheus Iglessias Mazzochi -MM [Originally published on Facebook March 17, 2021]

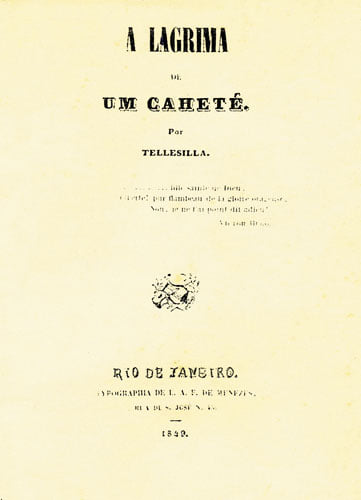

Today I bring three fragments from Nísia’s poem A Lágrima de um Caeté (Tear of a Caeté). The poem was published in 1849 in Rio de Janeiro, the same year that Revolução Praieira [1] ended. In it, Nísia sings for the oppressed First Natives, who were pictured by Romanticist Brazilian poets as willingly accepting colonization. Clearly, Nísia disagrees with that image. Because of the political instability of that time, and due to the violent resolution of Revolução Praieira by Brazilian Empire [2], there is a parallel between the government that oppressed the First Natives and the government that oppressed the liberals. The poem had two editions (both from 1849) and Nísia signs it as “Tellesilla”, an ancient Greek poet from Argos who was against oppression. “First Natives of Brazil, what are you? Savages? You don’t enjoy your goods anymore… Civilized? No… Your caring tyrants Keep you away from such weapons that have been hurting you Poor Cablocos! You don’t have any degree!... You lost everything, Except the infamous title of coward… * The Caetes’ venerated spirits are avenged! Sadly abandoned, without land, without goods, Blindly following your master’s voice You have lost your purity and traditions. * From Amazonas to Prata, The people are crying: - Enough, terrible monster, Your empire is crumbling! But you, my poor Caete, Listens to the Truth: Go seek the forests, only there You will be free. What do you make of these passages? To me, they are about the loss of identity of a people due to oppression. The “First Natives of Brazil” have lost “everything”. They cannot say who they are, and if they do, it doesn’t matter anymore. Just like the enslaved people. Also, they “have lost their traditions”. The Europeans call them “savage” when they are living in the forests. When they are not, after being brought to the cities and have lost their “purity”, they are called “coward”. Europeans and Brazilians call themselves “civilized” because they fulfill conditions of a “civilized” culture, conditions not created and not consented to by either the First Natives or the enslaved people. In this poem, Nísia avenges the First Natives, the Caetes. She does so to ensure they are not to be forgotten. However, the oppression that took their freedom and identity happens among the same people. The “Empire is crumbling”, Nísia says, and such proposition can be heard from North to South of Brazil (Amazonas River to Prata River). Thus, it seems that she is saying that the same government that oppresses the First Natives and the enslaved people is oppressing its own people. ____ [1] The Revolução Praieira was one of the many revolutions that were happening during the Brazilian Empire (1822-1889). Want to know more? Here is a reliable link that can be translated by Google about the Revolução Praieira: https://brasilescola.uol.com.br/.../revolucao-praieira.htm [2] Dom Pedro I proclaimed the Brazilian independence on September 7th, 1822. The country became an Empire until November 15th, 1889, when a military coup by Marshal Manuel Deodoro da Fonseca happened, making Brazil a republic. Here is a good link from Encyclopaedia Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/place/Brazil/Independence ----- Indígenas do Brasil, o que sois vós? Selvagens? os seus bens já não gozais... Civilizados? não... vossos tiranos Cuidosos vos conservam bem distantes Dessas armas com que ferido tem-vos De sua ilustração, pobres Cablocos! Nenhum grau possuís!... Perdeste tudo, Exceto de covarde o nome infame... * Dos Caetés os manes vingados estão! Em triste abandono, sem Pátria, sem bens, Às cegas seguindo a voz de um senhor Pureza e costumes perdido tu tens!... * [...] Do Amazonas ao Prata O povo lhe está bradando: - Sacia-te monstro atroz, Teu império está finando! Mas tu meu pobre Caeté Escuta a Realidade; Busca as matas, lá somente Gozarás da Liberdade Passages retrieved from: A Lágrima de um Caeté / Nísia Floresta Brasileira Augusta; Org. Constância Lima Duarte. 4. ed. Natal: 1997. 66p. Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN): https://www.bing.com/search... Translated by Matheus Iglessias Mazzochi Picture from http://www.projetomemoria.art.br/NisiaFl.../popups/044b.html -MM [Originally published on Facebook March 12, 2021]

Our first post about Nísia Floresta is from Opúsculo Humanitário, a book she published in 1853 in Rio de Janeiro. In it, Nísia famously argues that society’s progress can only be evaluated by how important women are in it. Although Nísia criticizes (the lack of) women’s education in Brazil in her book, she also talks about slavery. A link to the book is available in the end of this post as well as the original passage (in Portuguese). Chapter XLII (pp. 103-104) “Having all housekeeping being done by slaves, the girl finds herself surrounded by pernicious lessons since her first infancy. She observes behaviours and listens to words of such unfortunate race (people?), which is demoralized by captivity and condemned by the whip. Her sensibility gradually becomes familiar with such distressing show, which repeats almost daily in front of her; it is not rare to see her (with horror we say) inflicting the cruelest treatment to her own wet nurse who breastfed her and is indifferently sold or rented as a useless burden. Such revolting ingratitude is one of the most despicable examples given to that girl, who will become a mother one day and will pass that to her own children! (...) Thus, that sprout of intelligence embedded in her grace develops under the most contrary conditions to its future fulfillment. And no one is mindful that childhood is receiving unfavorable impressions from such art, and as Homer said, it is recorded in the soul as is in a wax table, where all the traits are more or less distinct; impressions that, like a subtle poison, destroys her best natural dispositions.” One of the interesting things implied in this passage is the negative consequences of slavery to human’s development. Since slavery happens at home, “almost daily”, girls are “surrounded by pernicious lessons”. They learn through examples by observing how the slaved person is treated and by listening to the words spoken. Consequently, they learn how to treat other human beings. That is not good. Such education, “by the whip” as Nísia says, “destroys” our “best natural dispositions”, which seems to be the human sensibility. Worse than that, the child becomes ungrateful, apathetic to the woman who breastfed her by growing in such distressing environment. Breastfeeding is one of the first bond that a mother creates to her child. It is a primary human bond. In the end, slavery reduces that human bond to a thing that can be sold or rented. ____ Link to the passage: (https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433075997266...) Todo o serviço do interior das famílias sendo feito entre nós por escravos, a menina acha-se desde a primeira infância cercada de outras tantas perniciosas lições, quantas são as ocasiões em que observa os gestos, as palavras e os atos dessa infeliz raça, desmoralizada pelo cativeiro, e condenada à educação do chicote! Sua nascente sensibilidade se habitua gradualmente a esse espetáculo afligidor, repetido quase diariamente a sua vista; não é raro ver ela (com horror o dizemos) infringir o mais cruel tratamento à própria ama que a amamentou, a qual é alguma vez indiferentemente vendida ou alugada como um fardo inútil, apenas acaba de ser-lhe necessária! Esta revoltante ingratidão é um dos mais detestáveis exemplos dados à menina, que tendo um dia de ser mãe, o transmite por seu turno a seus filhos! (...) Assim, aquele embrião de inteligência envolvido na epiderme de uma graça factícia desenvolve-se nas condições mais contrárias ao seu futuro engrandecimento. E ninguém atenta para as desfavoráveis impressões que de esta arte vai a infância recebendo, e gravando na cera, que conforme a expressão de Homero tem-se na alma, onde se conservam com traços mais ou menos distintos; impressões que semelhante a sutil veneno lhe destroem por vezes as melhores disposições naturais. -MM [originally published on the New Narratives Facebook page on 5 March 2021]

Dionísia Gonçalves Pinto, also known as Nísia Floresta Brasileira Augusta, is our woman philosopher of March. I’m going to briefly talk about her life here, and we’ll look at some interesting passages of her works next week. Nísia Floresta was born on October 12th, 1810, in a small town called Papari, in the Northeastern Brazil. Today, the city is called Nísia Floresta to honour her. Nísia’s name is a penname. “Nísia” is a short name from “Dionísia”. “Floresta” is the name of the place she was born at, “Brasileira” means Brazilian, and “Augusta” is a tribute to her spouse, Manuel Augusto. Nísia Floresta is considered to be the first Brazilian woman to publicly talk about women’s rights and to have her own column in her local newspaper. She published 15 books that were translated into English, Italian, and French. One of her books, Consigli a mia figlia, had two editions in Italy and was studied at Venetian schools. She travelled to Italy, England, Greece, France, Germany and Portugal, and compared how those countries treated women. She interacted with other leading intellectuals such as Almeida Garret, Alexandro Herculano, Alexandre Dumas, Victor Hugo, and Auguste Comte. Hugo and Comte were her close friends as their letters show. Her first book was published in 1832, when she was 22 years old. In Direitos das Mulheres e Injustiça dos Homens, Nísia questioned the quality of women’s education in Brazil. There were three editions for this book. A few years later, Nísia founded two schools, Augusto and Brasil, where History, Mathematics and Latin were taught to women. Both schools were considered scandalous at that time. Her first poem was published in 1849. In A lágrima de um Caeté, Nísia explored the degradation of Brazilian first natives through the exploitation of white men, mentioning rapes, land appropriation, and cultural destruction. She also mentioned the horror of one of many civil wars that were emerging in a Brazil before the Republic. Because she explored not only the suffering of women during the Revolução Praieira, but also of everybody, Nísia gained the attention, and further, the respect of Brazilian liberals. In 1853, Nísia wrote her masterpiece called Opúsculo Humanitário, a collection of essays defending women’s emancipation. In it, Nísia presents her famous argument that society’s progress can only be evaluated by how important women are in it. She died of pneumonia in Rouen, France, in 1885. -MM Picture retrieved for research purposes from: Museu Nisia Floresta (Facebook Page) https://www.facebook.com/museunisiafloresta.rn/photos/1246164508821619 [Originally published on Facebook 24 February 2021]

Our last post about Mary Ann Shadd Cary is about a sermon. We know little about this sermon, only that it was delivered to an audience in Chatham, Ontario, in 1858. The more we read it, the more complex it becomes. What is it about? Naturally, there is an abolitionist theme. However, how to understand sentences such as “The spirit of true philanthropy knows no sex” or “She (woman) too is a neighbour”? Here is one of the intro paragraphs. “These two great commandments [to love the Lord our God with heart and soul, and our neighbour as our self], and upon which rest all the Law and the prophets, cannot be narrowed down to suit us but we must go up and conform to them. They proscribe neither nation nor sex – our neighbour may be either the oriental heathen, the degraded Europe and or the enslaved colored American. Neither must we prefer sex the slave-mother as well as the slave-father”. This sermon is about more than just the colour of our skin. To me, it’s about love. Love that is both to “the Lord our God”, to “our neighbour”, and to ourselves too. Love “upon which rest all the Law and the prophets”, and that “cannot be narrowed down to suit us”, but that “we must go up and conform to” it. Further in the sermon, Mary Ann Shadd Cary says that we should “waive all prejudices of education, birth, nation or training” to practice that kind of love. That illustrates that she is not talking about sexual or bodily love; she is talking about transcendental love. A love that goes beyond our attributes such as color or sex, for instance. The word “neighbor” could mean everyone. Someone who has a different religious belief than us (“the oriental heathen”), someone whom we don’t respect (“the degraded Europe”), or someone who has been deprived of what we may take for granted (“the enslaved colored American”). But, if we have to consider everyone as our “neighbours” and we have to love them as we would like to be loved, then what would happen to slavery or to inequality? In the end of her sermon, Mary Ann Shadd Cary says that we’re all equal because we share a “common origin”, and were it not for “the monster slavery, we would have a common destiny here.” The meaning of “here” is open to interpretation, but I think she is not limiting her sermon to Chatham, Ontario, April 6th 1858. That is why we’re still talking about her in 2021. --MM [Originally published on Facebook on 17 February 2021]

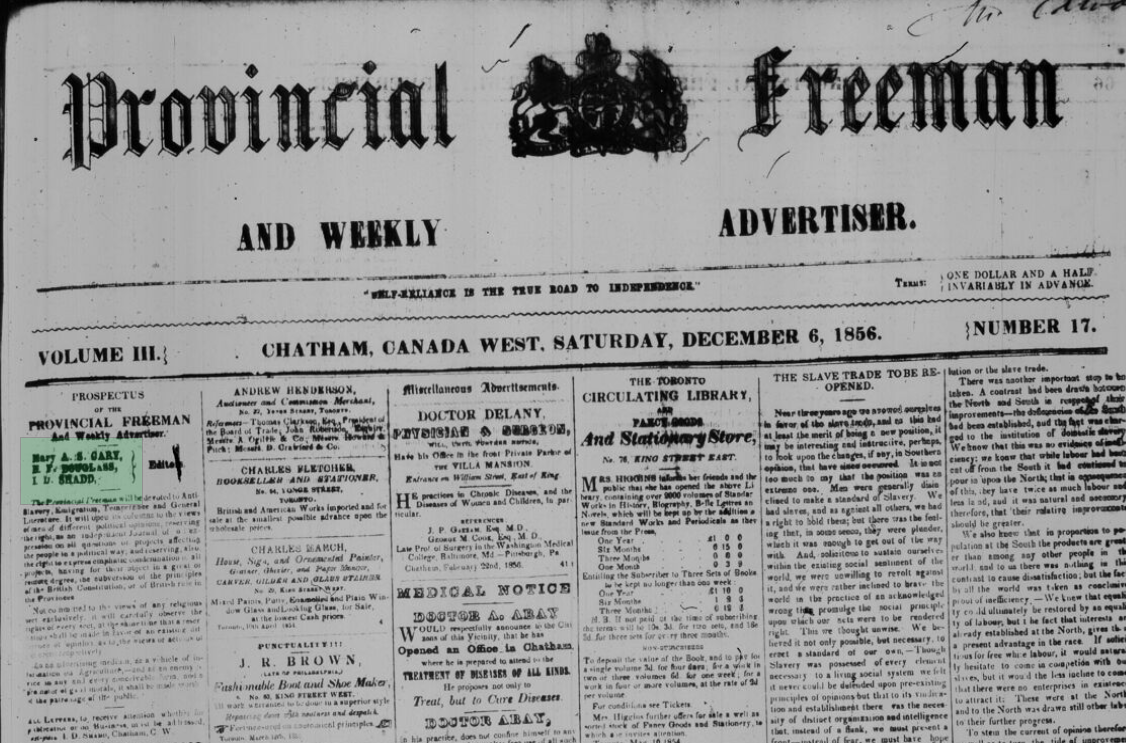

Last week, we talked about Mary Shadd Cary’s A Plea for Emigration. Today, I bring her editorial about the United States presidential election in 1856. Here is a passage: “Instead of a handful of abolitionists, from motives of humanity, the world beholds millions of abolitionists from necessity, and depend upon it there will be hard and bloody work, before the struggle terminate[s]! We heartly deplore the prospect. There is no one so thoroughly depraved! as to love violence for its own sake, but the oppressor of the colored man has forced the necessity” Her words are provocative, aren't they? There will be “hard and bloody” work. Violence will happen whether one protests against slavery or not. The election result shows that slavery is not going to be solved through politics. There is a moral difference among people. It is not a matter of opinion or of facts, it is a matter of moral principles. On one hand, some people believe that slavery is morally acceptable; on the other hand, some do not. Those who do not happen to be oppressed by the former. How to solve that when you do not have rights to protect you and the only people who can recognize those rights into laws are against you? In such scenario, Mary Shadd Cary says that you do not solve this problem without “hard and bloody work”. Violence for its own sake is not morally justifiable, but if all forms of peaceful resolutions are doom to fail, violence as a mean to a greater good may be. It is interesting and cool to see that Philosophy can be found in a newspaper editorial. Next week, we will see that it can be found in a sermon. For historical background: in 1856, James Buchanan was elected the 15th president of the United States. Mary Shadd Cary’s editorial was written two weeks after the election result. She said that “A fearful thing is the result of that last presidential election!”. For her, United States politics was not about being Republican or Democrat; it was about being abolitionist or pro-slavery. Since 1854, the growing apathy towards slaved people, the persecution of abolitionists, and the inefficacy of debates on whether or not slavery was morally acceptable had caused violent riots such as the one known as “Bleeding Kansas”. Mary Shadd Cary’s editorial was predicting that things were going to get worse. Five years after Mr. Buchanan’s election, the United States entered in civil war. --MM Picture retrieved from Canadiana - by Canadian Research Knowledge Network (CRKN) – for research use: |

Authors

Jacinta Shrimpton is a PhD student in Philosophy at the University of Sydney. She is co-producer of the ENN New Voices podcast Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed