|

Welcome to the first episode of New Voices in Philosophy. In this episode, Haley Brennan talks with Sergio Gallegos Ordorica, an assistant professor at John Jay College, about the Mexican philosopher Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. We talk about how Sergio became interested in studying Sor Juana as a philosopher, how that study can be complicated by a background in analytic philosophy, some of Sor Juana’s views on love, shame, and the self, and how her identity as a Mexican women shaped her philosophy, including her views on how philosophy can be done absent institutional structures.

Marya Jureidini provided research for this episode. To listent to this episode, please visit our podcast page. Thank you for listening! Texts Mentioned/Referred to in the Episode Works by Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

English Translations

[we highlight in bold some secondary sources that are a good place to start further research] Other Works Discussed and Mentioned

Further Reading

0 Comments

a post by Haley Brennan and Olivia Branscum

This is New Voices, a podcast from the Extending New Narratives in the History of Philosophy project.

This podcast consists of conversations with contemporary philosophers working on historical philosophers that are members of groups underrepresented or not very often studied or taught in a Western professional philosophical context. We talk about the views of these philosophers: what is interesting about them, what is unique about them, how they fit in to the periods that they were apart of. We also talk about what it is actually like to learn about and promote these ideas as a philosopher today: what benefits there are, what challenges there are, and just how to get going on this work. The conversation in each episode is between a graduate student and a working philosopher, with input and questions from undergraduate researchers. Altogether, we aim to both introduce new or understudied figures and themes, and show how they have captured interest. The episodes highlight what is valuable and exciting about reading and studying these new voices at all different career stages and with all sorts of different academic backgrounds. New Voices is produced and hosted by Olivia Branscum and Haley Brennan. Olivia is a graduate student in philosophy at Columbia University who works on late medieval and early modern philosophy of mind and metaphysics, as well as philosophy of art and environmental ethics and aesthetics. Haley is a graduate student in philosophy at Princeton University who works on historical (17th, 18th, and 19th c) and contemporary metaphysics and philosophy of mind, with a focus on the metaphysics and ethics of the self and identity. They are joined by a team of undergraduate researchers with wide-ranging interests in underrepresented figures in philosophy: Madeline Hope Birdsell, Marya Jureidini, Makena Yananiso Kiara, Petru Rosa, and Selina Wang. We’ve had a lot of fun putting together this podcast, and we hope you tune in! A new episode will be available on the last day of every month, starting with our first episode—an interview with Sergio Gallegos Ordorica on studying Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz—on June 30th. Episodes can be found on iTunes, Spotify, or our website, newnarrativesinphilosophy.net/podcast. New Voices is a continuation of the New Narratives in the History of Philosophy podcast: past episodes can be found under that name in all the same places. [Originally published on Facebook 30 April 2021]

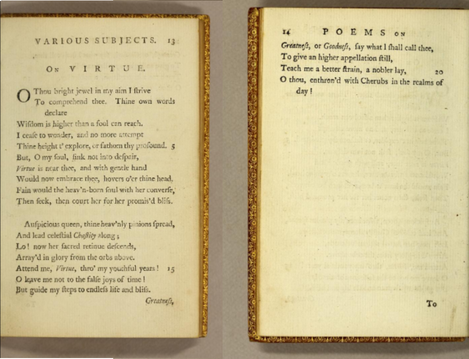

Our third and last poem is called, “On Virtue”, and it also belongs to Phillis’ poetry collection entitled, “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral” that was published in 1773. As always, a link to the digitized version is provided at the end of this post. Enjoy the poem: O thou bright jewel in my aim I strive To comprehend thee. Thine own words declare Wisdom is higher than a fool can reach. I cease to wonder, and no more attempt Thine height t’explore, or fathom thy profound. But, O my soul, sink not into despair, Virtue is near thee, and with gentle hand Would now embrace thee, hovers o’er thine head. Fain would the heaven-born soul with her converse, Then seek, then court her for her promised bliss. Auspicious queen, thine heavenly pinions spread, And lead celestial Chastity along; Lo! now her sacred retinue descends, Arrayed in glory from the orbs above. Attend me, Virtue, thro’ my youthful years! O leave me not to the false joys of time! But guide my steps to endless life and bliss. Greatness, or Goodness, say what I shall call thee, To give a higher appellation still, Teach me a better strain, a nobler lay, O Thou, enthroned with Cherubs in the realms of day! Here, it seems that Virtue and Wisdom are related, and that Virtue is a means to Wisdom. Ordinary people (the “fool”) cannot reach Wisdom because Wisdom is too high. This could make us “to cease to wonder, and no more attempt/ Thine height t’explore, or fathom thy profound”. What is left for us besides having our soul sinking “into despair”? Virtue. Virtue can not only save us from despair, but also it can serve as a guide to “endless life” and “promised bliss”. In other words, Wheatley is suggesting that Wisdom is not reached directly, but through Virtue. Thus, rather than seeking to be a wise person, she thinks we should seek to become a virtuous person first. Now, what do you make of “Teach me a better strain”? To me, Wheatley is talking about two things: what is seen and what is not. The colour of our skin is something that is seen; a virtuous soul is something that is not. It would not matter the colour of someone’s skin, for instance, but only whether that person is virtuous. Digitized Version [Internet Archive]: https://archive.org/.../poemsonvarioussu.../page/13/mode/1up -MM [Originally published on Facebook 22 April 2021]

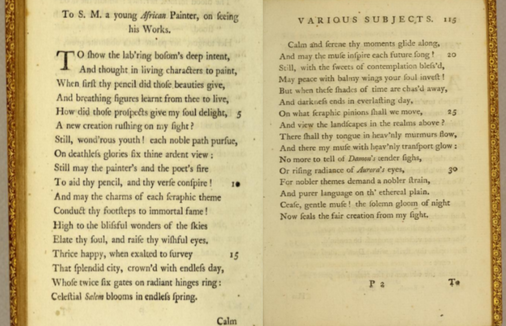

Our second poem is called, “To S.M., a Young African Painter, on Seeing His Works”. It belongs to Phillis’ poetry collection entitled, “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral” that was published in 1773. A link to the digitized version is provided at the end of this post. Here is the poem: To show the lab’ring bosom’s deep intent, And thought in living characters to paint, When first thy pencil did those beauties give, And breathing figures learnt from thee to live, How did those prospects give my soul delight, A new creation rushing on my sight? Still, wond’rous youth! each noble path pursue, On deathless glories fix thine ardent view: Still may the painter’s and the poet’s fire To aid thy pencil, and thy verse conspire! And may the charms of each seraphic theme Conduct thy footsteps to immortal fame! High to the blissful wonders of the skies Elate thy soul, and raise thy wishful eyes. Thrice happy, when exalted to survey That splendid city, crown’d with endless day, Whose twice six gates on radiant hinges ring: Celestial Salem blooms in endless spring. Calm and serene thy moments glide along, And may the muse inspire each future song! Still, with the sweets of contemplation bless’d, May peace with balmy wings your soul invest! But when these shades of time are chas’d away, And darkness ends in everlasting day, On what seraphic pinions shall we move, And view the landscapes in the realms above? There shall thy tongue in heav’nly murmurs flow, And there my muse with heav’nly transport glow: No more to tell of Damon’s tender sighs, Or rising radiance of Aurora’s eyes, For nobler themes demand a nobler strain, And purer language on th’ ethereal plain. Cease, gentle muse! the solemn gloom of night Now seals the fair creation from my sight. This poem shows us that there can be philosophical topics in poetry, topics from Philosophy of Art, or Aesthetics, including: beauty and the problem of expressing the eternal in the human realm, the aesthetical effect provoked by the author and the possibility of such an effect, timelessness or the eternal, including the nature of space in heaven. Wheatley also mentions the relationship between poetry and painting, as if both the poet and the painter conspire. Although we could continue to think broadly about such topics, it is interesting to note one particularity. Both Wheatley and the painter have something in common besides being a creator of life (a “poetes”, ποιητης). They are of the same strain. In this context, we understand “strain” as being of race, generation. By the title, this poem is to a young African painter; by the author, this poem is by an African poet. What would you think that Wheatley had in mind when she wrote this poem about an African painter in 1773? Digitized version [Internet Archive]: https://archive.org/.../poemsonvariouss.../page/114/mode/1up -MM [Originally published on Facebook April 14, 2021]

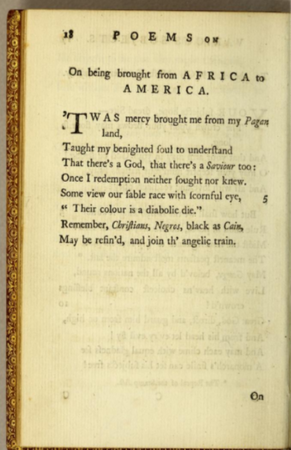

Our first poem of Phillis Wheatley is called “On Being Brought from Africa to America”, and it was published in 1773 in her poetry collection “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral”. We provide a link to the digitized version of her collection at the end of the post. Here is the poem: ‘Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land, Taught my benighted soul to understand That there’s a God, that there’s a Saviour too: Once I redemption neither sought nor knew. Some view our stable race with scornful eye, “Their colour is a diabolic die.” Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain, May be refin’d, and join th’angelic train. There are some interesting conflicts. Firstly, Phillis opens her poem saying that “ ‘twas mercy” who brought her, not slavery. Secondly, she calls her land pagan as if she ignores (we don’t know whether voluntarily or not) the sacrality of the beliefs of her homeland. The third line reinforces that idea, as if there was no God, no “saviour” in Africa, which makes us to wonder if Phillis accepted her past or not. In the fourth line, redemption was not sought by her maybe because she did not know about it. It seems that ignorance makes us away from redemption. However, that same ignorance can be found in America too because some “view our stable race with scornful eye” believing that “their colour is a diabolic die”. This apparent shift of where ignorance lies makes the end of the poem ambiguous: to whom is she talking? Who is her audience? Is she asking all Christians to remember that “Negros”, who are “black as Cain, may be refin’d, and join th’angelic train” or is she asking everyone to remember that both Christians and “Negros” could be “black as Cain”, and that both “may be refin’d, and join th’angelic train”? Finally, was this ambiguity intentional by the poet? What do you think? Digitized Version [Internet Archive]: https://archive.org/.../poemsonvarioussu.../page/18/mode/1up [Originally published on Facebook April 9, 2021]

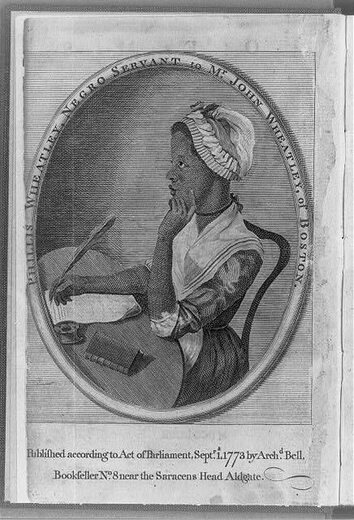

Phillis Wheatley, the first African American to publish a book of poems, is our woman philosopher of April. She was born in the Republic of Gambia, in the western part of Africa, it is thought in 1753. At the age of 8, Phillis was brought to America as a slave, when she was bought by the Wheatley family in Boston, Massachusetts. Hence, her last name. Her first name is due to the ship that brought her, the Phillis. The Wheatley family taught her Astronomy, Geography, Literature, English, Ancient Greek and Latin. After 16 months, Phillis could read the Bible, Greek and Latin classics (in Greek and in Latin), and British Literature. In 1767, Phillis published her first poem, “On Messieurs Hussey and Coffin”. In 1770, she published “An Elegiac Poem, on the Death of the Celebrated Divine, and Eminent Servant of Jesus Christ, the Reverend and Learned George Whitefield”, which brought her notoriety. In 1773, she went to London to publish her collection of poems called “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral”. There, Phillis met people such as Baron George Lyttleton, Sir Brook Watson, John Thorton, and Benjamin Franklin. The travel was sponsored by the English Countess of Huntington, Selina Hastings. Her book is considered a landmark achievement in the US history. Due to the unusual fact that the book was written by a slave, her book included a preface with 17 Boston notable men attesting that it was indeed written by Phillis, a slave. John Hancock, who signed the United States Declaration of Independence, was among those men. Phillis was emancipated after the book’s publication. Defender of freedom and liberty, Phillis wrote poems supporting America’s fight for independence. Let me mention here the poem called “His Excellency General Washington”, which was sent by Phillis directly to Gen. George Washington in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1775. One year later, Washington invited Phillis to visit him. She accepted. Other themes in her poems include: religious rites, death, and slavery. She died on December 5, 1784, due to complications from childbirth. It is believed that she wrote 145 poems. Her work contributed to American literature, and her literary and artistic talents helped to demonstrate that African Americans were equally capable, creative, intelligent human beings who benefited from an education, helping the cause of the abolition movement. If you want to know more about her, take a look at these websites: National Women's History Museum (US): https://www.womenshistory.org/.../biogra.../phillis-wheatley Biography: https://www.biography.com/writer/phillis-wheatley Poetry Foundation: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/phillis-wheatley -MM [Originally published on Facebook March 31, 2021]

Our last post on Nísia Floresta is from Opúsculo Humanitário, which is the same book from our first post, and is about women’s education. Here is the passage: XXVI (p.59 of the book; 69 of the digitized version) “The more ignorant a nation is, the easier it is for an absolute government to exercise its unlimited power over it. It is from that principle, so contrary to the progressive march of civilization, that most men are against making easier how women cultivate their spirit. However, this is a mistake that has been and always will be contrary to the prosperity of nations as well as is contrary to the domestic fortune of men. (…) Just as a paternal government is the most proper one to make people happy, and a properly cultivated intelligence of those nations is the best incentive for them to fulfill their duties, so too is moral education the safest guide to women. It is the pole star that indicates their north, in the fragile struggle in which they have to navigate as a ship in the sea, a sea seeded with abrolhos (pointed coral reefs), which is called life. The lack of a good education is the primary cause that contributes to women to lose their north, which is nothing else but morality, in the midst of the corruption of society. Always seeking to hold their intelligence, to weaken their senses, they make women unable to occupy, as they should to begin with, the care of purifying their heart; women would never advantageously achieve such thing if their intelligence remains without culture.” As we have seen, Nísia Floresta was against slavery because it is a form of oppression of one people over another. Such oppression can be instantiated in many varieties: it can manifest on basis of color (Europeans to Africans), political views (Italian liberals versus their government and Brazilian liberals versus the Empire), or culture (colonization over the First Natives). This passage shows us that Nísia thinks that lack of education could be another instantiation of oppression because it willingly hinders the moral development of human beings. Since men were “against making easier” for women to learn, men were willingly hindering women’s moral development. Therefore, men were oppressing women. Thus, Nísia finds a common ground between colonized First Natives, enslaved people and women: they were all devoid of education. Worse than that, they were deprived of education by the oppressor, whoever it be. Further, Nísia compares the political influence of an absolute government over an ignorant nation to the power of men over women. Such comparison allows us to consider despotic governments as oppressors too. Thus, we may say that Nísia was against a universal form of oppression, a form that can be instantiated differently. If such oppression is justified by color, we call Nísia an abolitionist; if it is justified by sex, we call her a feminist, and so forth… However, I cannot make something of “a paternal government is the most proper one to make people happy”. She seems to be listing kinds of “guides”. Moral education is “the safest guide” for women. Cultivated intelligence is “the safest guide” for a nation that seeks the fulfilment of its duties. A paternal government is “the safest guide” to make people happy. Was she defending paternal governments or was she just saying that it does not matter how bad a ruler is, if the ruler rules paternally, then the people will not care? If the latter, she may have said that ironically, criticizing paternal governments. __ Retrieved from: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433075997266... Original in Portuguese: “Quanto mais ignorante é um povo, tanto mais fácil é a um governo absoluto exercer sobre ele o seu ilimitado poder. É partindo deste princípio, tão contrário à marcha progressiva da civilização, que a maior parte dos homens se opõem a que se facilite à mulher os meios de cultivar o seu espírito. Porém, é este um erro, que foi e será sempre funesto à prosperidade das nações, como à ventura doméstica do homem. (...) Assim como um governo paternal é o mais próprio a fazer a felicidades dos povos, e a inteligência destes devidamente cultivada o melhor incentivo para o exato cumprimento de seus deveres; assim também a educação moral é o guia mais seguro da mulher, a estrela polar que lhe indica o norte, no frágil batel em que ela tem de navegar por esse mar semeado de abrolhos, a que se chama vida. A falta de uma boa educação é a causa capital, que contribui para que a mulher, no meio da corrupção da sociedade perca esse Norte, o qual não é outro mais que a moral. Procurando-se sempre prender-lhe a inteligência, enfraquecer-lhe os sentidos, inabilitam-na para ocupar-se, como devia, antes de tudo do cuidado de purificar o seu coração; o que nunca poderá ela vantajosamente conseguir se a sua inteligência permanecer sem cultura.” Translated by Matheus Iglessias Mazzochi -MM |

Authors

Jacinta Shrimpton is a PhD student in Philosophy at the University of Sydney. She is co-producer of the ENN New Voices podcast Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed