ENN New Voices: The Political Philosophy of Frederick Douglass: Interview with Phil Yaure10/31/2022 In this episode, Olivia speaks with Phil Yaure – assistant professor of philosophy at Virginia Tech University – about the political philosophy of Frederick Douglass. Douglass was born into slavery, but eventually became one of the most influential black abolitionists of the 19th century after escaping his enslaved condition and learning to read and write. Phil’s research focuses on Douglass as a political philosopher, with special concern for Douglass’s conception of the US constitution as an anti-slavery document and his belief that citizenship is a function of one’s contribution to a polity (in contrast to thinking of citizenship as a status that is conferred upon someone by the powers of the state). Phil argues that Douglass considers abolitionist resistance itself to be a way of contributing to American society, which leads to the conclusion that enslaved people fighting against the injustice of slavery make themselves American citizens in doing so. We also discuss the philosophical value of the autobiography genre, and Phil offers listeners some recommendations for where to begin if they want to incorporate Frederick Douglass into their history of philosophy courses.

Further Reading Autobiographies: Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (by Douglass, originally published 1845) My Bondage and My Freedom (by Douglass, originally published 1855) The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (by Douglass, originally published 1881 and revised 1892) Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (by Harriet Jacobs, originally published 1861) Select Speeches by Douglass: “The Free Negro’s Place is in America” (delivered 1851) “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” (July 5 Speech) (delivered 1852) “Claims of our Common Cause: Address of the Colored Convention held in Rochester, July 6-8, 1853” (delivered 1853) Other Sources Mentioned: Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857) Birthright Citizens, Martha S. Jones (Cambridge University Press, 2018) Immigrants and the Right to Stay, Joseph H. Carens with Deborah Chasman (MIT Press, 2018) Immigration and Democracy, Sarah Song (Oxford University Press, 2019) To listen to this episode, please visit our podcast page.

0 Comments

In this episode, Haley Brennan speaks with Dalitso Ruwe, Assistant Professor of Black Political Thought at Queen’s University, about his project of locating and understanding genealogies of Black and African philosophy. We talk about 18th century ontological and Biblical arguments against slavery, the relationship between practical and intellectual revolutions, and what it means to disrupt a system. We also discuss the value of each person’s own philosophical genealogy, and how to find philosophical content in a text. This episode is the first of a series of interviews with New Narratives Postdocs, past and present.

Select Bibliography Frederick Douglass, “Letter from Frederick Douglass to his old master: extracted from the ‘North star’." The Derrick Bell Reader, edited by Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic. James W. C. Pennington, The Fugitive Blacksmith: or, Events in the History of James W. C. Pennington, Pastor of a Presbyterian Church, New York, Formerly a Slave in the State of Maryland, United States Negro Orators and their Orations, edited by Carter G. Woodson. Lift Every Voice: African American Oratory, 1787-1901, edited by Philip S. Foner and Robert Branham. Early Negro Writing, 1760-1837, edited by Dorothy Porter. Angela Davis, Abolition Democracy: Beyond Prisons, Torture, and Empire. John Henrik Clarke, Critical Lessons in Slavery and the Slave Trade: Essential Studies and Commentaries on Slavery, in General, and the African Slave Trade, in Particular. Elizabeth McHenry, Forgotten Reader: Recovering the Lost History of African American Literary Societies To listen to this episode, please visit our podcast page. In this episode, Haley Brennan talks with Dalia Nassar, senior lecturer in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Sydney. We discuss the works of several German women philosophers in the late 18th and 19th centuries, including Germaine de Staël, Rosa Luxemburg, and Karoline von Günderrode. The women we discuss wrote on a wide range of topics: idealism, phenomenology, feminism, labour movements, workers’ rights, socialism, and environmental ethics. In addition to these topics, we talk about why it is that these women, who published and were discussed in their own time, have not received modern philosophical attention, the accessibility of their philosophical writings, the importance of being aware of the full range of philosophers writing and corresponding in Germany in the 19th century, and the variety of benefits that come from including the works of these philosophers in classes on German philosophy in the 19th century. We also talk about the value of being flexible and open about what counts as philosophical question, and the ways that philosophy can be applicable to real-world issues.

To listen to this episode, please visit our podcast page. Works by German Women Philosophers Mentioned in the Episode Unless otherwise specified, all works listed are in the public domain and are available in the original language and (often) in English translation online. Germaine de Staël, De l’Allemange (On Germany). Bettina Brentano von Arnim, Die Günderrode. ——, Armenbuch (The Book of the Poor). Margaret Fuller, “Bettina Brentano and her friend Günderrode.” The Dial Vol VII. Clara Zetkin, “In Defence of Rosa Luxemburg.” ——, “Social-Democracy and Women’s Suffrage.” Karoline von Günderrode, “The Idea of the Earth.” Available in English in Women Philosophers in the Long Nineteenth Century: The German Tradition, edited by Dalia Nassar and Kristin Gjesdal. Rosa Luxemburg, “Wage Labour.” Available in English in Women Philosophers in the Long Nineteenth Century: The German Tradition, edited by Dalia Nassar and Kristin Gjesdal. Hedwig Dohm, “Nietzsche and Women.” Available in English in Women Philosophers in the Long Nineteenth Century: The German Tradition, edited by Dalia Nassar and Kristin Gjesdal. Other Works Mentioned Hegel, Lectures on the History of Philosophy. Copleston, A History of Philosophy. Further Reading Women Philosophers in the Long Nineteenth Century: The German Tradition, edited by Dalia Nassar and Kristin Gjesdal, New York: Oxford University Press, 2021. Nassar, Dalia. “The Human Vocation and the Question of the Earth: Karoline von Günderrode’s Philosophy of Nature.” Archiv für Geschichte der Philosophie 20, 2021. [Originally published on Facebook March 31, 2021]

Our last post on Nísia Floresta is from Opúsculo Humanitário, which is the same book from our first post, and is about women’s education. Here is the passage: XXVI (p.59 of the book; 69 of the digitized version) “The more ignorant a nation is, the easier it is for an absolute government to exercise its unlimited power over it. It is from that principle, so contrary to the progressive march of civilization, that most men are against making easier how women cultivate their spirit. However, this is a mistake that has been and always will be contrary to the prosperity of nations as well as is contrary to the domestic fortune of men. (…) Just as a paternal government is the most proper one to make people happy, and a properly cultivated intelligence of those nations is the best incentive for them to fulfill their duties, so too is moral education the safest guide to women. It is the pole star that indicates their north, in the fragile struggle in which they have to navigate as a ship in the sea, a sea seeded with abrolhos (pointed coral reefs), which is called life. The lack of a good education is the primary cause that contributes to women to lose their north, which is nothing else but morality, in the midst of the corruption of society. Always seeking to hold their intelligence, to weaken their senses, they make women unable to occupy, as they should to begin with, the care of purifying their heart; women would never advantageously achieve such thing if their intelligence remains without culture.” As we have seen, Nísia Floresta was against slavery because it is a form of oppression of one people over another. Such oppression can be instantiated in many varieties: it can manifest on basis of color (Europeans to Africans), political views (Italian liberals versus their government and Brazilian liberals versus the Empire), or culture (colonization over the First Natives). This passage shows us that Nísia thinks that lack of education could be another instantiation of oppression because it willingly hinders the moral development of human beings. Since men were “against making easier” for women to learn, men were willingly hindering women’s moral development. Therefore, men were oppressing women. Thus, Nísia finds a common ground between colonized First Natives, enslaved people and women: they were all devoid of education. Worse than that, they were deprived of education by the oppressor, whoever it be. Further, Nísia compares the political influence of an absolute government over an ignorant nation to the power of men over women. Such comparison allows us to consider despotic governments as oppressors too. Thus, we may say that Nísia was against a universal form of oppression, a form that can be instantiated differently. If such oppression is justified by color, we call Nísia an abolitionist; if it is justified by sex, we call her a feminist, and so forth… However, I cannot make something of “a paternal government is the most proper one to make people happy”. She seems to be listing kinds of “guides”. Moral education is “the safest guide” for women. Cultivated intelligence is “the safest guide” for a nation that seeks the fulfilment of its duties. A paternal government is “the safest guide” to make people happy. Was she defending paternal governments or was she just saying that it does not matter how bad a ruler is, if the ruler rules paternally, then the people will not care? If the latter, she may have said that ironically, criticizing paternal governments. __ Retrieved from: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433075997266... Original in Portuguese: “Quanto mais ignorante é um povo, tanto mais fácil é a um governo absoluto exercer sobre ele o seu ilimitado poder. É partindo deste princípio, tão contrário à marcha progressiva da civilização, que a maior parte dos homens se opõem a que se facilite à mulher os meios de cultivar o seu espírito. Porém, é este um erro, que foi e será sempre funesto à prosperidade das nações, como à ventura doméstica do homem. (...) Assim como um governo paternal é o mais próprio a fazer a felicidades dos povos, e a inteligência destes devidamente cultivada o melhor incentivo para o exato cumprimento de seus deveres; assim também a educação moral é o guia mais seguro da mulher, a estrela polar que lhe indica o norte, no frágil batel em que ela tem de navegar por esse mar semeado de abrolhos, a que se chama vida. A falta de uma boa educação é a causa capital, que contribui para que a mulher, no meio da corrupção da sociedade perca esse Norte, o qual não é outro mais que a moral. Procurando-se sempre prender-lhe a inteligência, enfraquecer-lhe os sentidos, inabilitam-na para ocupar-se, como devia, antes de tudo do cuidado de purificar o seu coração; o que nunca poderá ela vantajosamente conseguir se a sua inteligência permanecer sem cultura.” Translated by Matheus Iglessias Mazzochi -MM [Originally posted on Facebook March 24, 2021.]

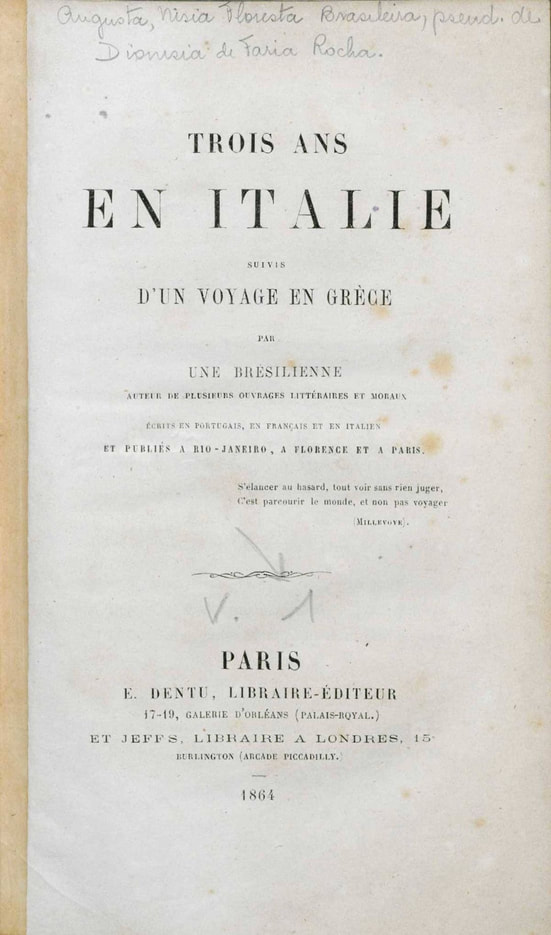

Our fourth post on Nísia Floresta is from “Trois ans en Italie: suivis d’un voyage en Gréce” (Three years in Italy followed by a trip to Greece). This book was published in 1864 in France, but only was translated into Portuguese in 1998. The book is not only a journal of her trips throughout Italy and Greece, full of descriptions of the landscapes and architecture; it is an analysis of the history and political development of those nations. In it, Nísia foresees the Italian Unification [1]. Here is an interesting passage: “If such rebellions [2] were never to be excusable, (…) could the same be said about the savage representatives of noble races (the black enslaved), whom are tortured with humiliating punishments? Furthermore, if war, this infernal scourge whose existence must be banned among all civilized people, can be somehow excused, then it must be done to free our land against the tyrant invaders whom claimed themselves sovereigns. Italy has been tormented, not for days, months, or years, but for centuries, by the despotic yoke of all kinds of conquerors. Its war, therefore, is excusable and even just (…) Italy has risen because its brave sons escaped from the heavy prisons in which they were chained by their tyrants. The spoiled motherland, looking at its noble sons, divided and enslaved by the ambitious despotism of foreign usurpers, finally regained freedom and, likewise, its rights” (pp.317-318). This is a subtle passage. If the Italian rebellions are not excusable for fighting against oppression and for the right to be free, then the same could be said to any rebellion by “the savage representatives of noble races”. But we do consider the Italian rebellions excusable. So, we must consider as excusable any rebellion made by the “noble races”. And by “noble races” Nísia means the black enslaved. It is a powerful analogy and it is logically valid (it is a Modus Tollens). She goes on to state the reasons of the Italian rebellions, leaving us to continue her analogy. Their rebellions are excusable because they fight against “tyrant invaders whom claimed themselves sovereigns”. This is a just cause for Nísia. The Italians were enslaved by “ambitious despotism of foreign usurpers” and they just seek freedom and rights. Is not that what happened in Africa with the African people? Since both Italians and Africans share the same burden of slavery by foreigners and the claim for freedom, to advocate for the Italian unification would be to advocate against slavery. Here, “slavery” is meant in the broad sense: of one nation over another. Thus, it does not reference the color, the language, or the culture of the nation. If one nation is oppressing, enslaving another, it is not right. Thus, any rebellion that claims freedom and rights is excusable and justified. In one single passage, Nísia praises the Italian unification and defends abolitionism. ----- Retrieved from: https://memoria.ifrn.edu.br/.../Tr%c3%aas%20anos%20na... Original in French: 1st Volume: http://objdigital.bn.br/.../drg291826/drg291826.html... 2nd Volume: http://objdigital.bn.br/.../drg1414580/drg1414580.html... [1] Also known as “Risorgimento” (Resurgence), the Italian Unification was the historical process which unified Italian kingdoms into one, resulting the Kingdom of Italy in March 17th, 1861. It was a consequence of the ideas of French revolution that were brought by Napoleon’s troop to Italy when he was at war with Austria. Here is a good article of Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/place/Italy/Unification [2] Here Nísia is referring to the many rebellions that were emerging in Italy prior to its unification. She explains them in previous pages. Although King Francisco II defeated Garibaldi’s troops in Naples, Garibaldi himself won battles against General Landi in Sicily, such as the battle of Calatafimi, and in Munrriali. * Se a revolta jamais fosse desculpável, (...) o mesmo poderia se afirmar em relação a selvagens representantes de raças nobres (escravos negros), a quem se tortura com degradantes castigos? Além disso, se a guerra, flagelo infernal cuja existência deve ser banida dentre todos os povos civilizados, pode ser de alguma forma desculpada, é preciso ser feita para livrar a nossa terra dos tiranos invasores que se fizeram soberanos. A Itália gemeu, não por dias, meses ou anos, mas durante séculos, sob o jugo despótico de todo tipo de dominadores. Sua guerra, pois, é desculpável e até mesmo justa, (...) A Itália ressurgiu em virtude de seus bravos filhos terem escapado das pesadas cadeias com que foram acorrentados por seus tiranos. A espoliada mãe pátria, olhando para seus nobres filhos secularmente divididos e escravizados pelo despotismo ambicioso de usurpadores estrangeiros, recobrou finalmente a liberdade e, da mesma forma, seus direitos. (pp.317-318) Translated by Matheus Iglessias Mazzochi -MM |

Authors

Jacinta Shrimpton is a PhD student in Philosophy at the University of Sydney. She is co-producer of the ENN New Voices podcast Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed