ENN New Voices: The Political Philosophy of Frederick Douglass: Interview with Phil Yaure10/31/2022 In this episode, Olivia speaks with Phil Yaure – assistant professor of philosophy at Virginia Tech University – about the political philosophy of Frederick Douglass. Douglass was born into slavery, but eventually became one of the most influential black abolitionists of the 19th century after escaping his enslaved condition and learning to read and write. Phil’s research focuses on Douglass as a political philosopher, with special concern for Douglass’s conception of the US constitution as an anti-slavery document and his belief that citizenship is a function of one’s contribution to a polity (in contrast to thinking of citizenship as a status that is conferred upon someone by the powers of the state). Phil argues that Douglass considers abolitionist resistance itself to be a way of contributing to American society, which leads to the conclusion that enslaved people fighting against the injustice of slavery make themselves American citizens in doing so. We also discuss the philosophical value of the autobiography genre, and Phil offers listeners some recommendations for where to begin if they want to incorporate Frederick Douglass into their history of philosophy courses.

Further Reading Autobiographies: Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (by Douglass, originally published 1845) My Bondage and My Freedom (by Douglass, originally published 1855) The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (by Douglass, originally published 1881 and revised 1892) Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (by Harriet Jacobs, originally published 1861) Select Speeches by Douglass: “The Free Negro’s Place is in America” (delivered 1851) “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” (July 5 Speech) (delivered 1852) “Claims of our Common Cause: Address of the Colored Convention held in Rochester, July 6-8, 1853” (delivered 1853) Other Sources Mentioned: Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857) Birthright Citizens, Martha S. Jones (Cambridge University Press, 2018) Immigrants and the Right to Stay, Joseph H. Carens with Deborah Chasman (MIT Press, 2018) Immigration and Democracy, Sarah Song (Oxford University Press, 2019) To listen to this episode, please visit our podcast page.

0 Comments

In this episode, Haley Brennan speaks with Dalitso Ruwe, Assistant Professor of Black Political Thought at Queen’s University, about his project of locating and understanding genealogies of Black and African philosophy. We talk about 18th century ontological and Biblical arguments against slavery, the relationship between practical and intellectual revolutions, and what it means to disrupt a system. We also discuss the value of each person’s own philosophical genealogy, and how to find philosophical content in a text. This episode is the first of a series of interviews with New Narratives Postdocs, past and present.

Select Bibliography Frederick Douglass, “Letter from Frederick Douglass to his old master: extracted from the ‘North star’." The Derrick Bell Reader, edited by Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic. James W. C. Pennington, The Fugitive Blacksmith: or, Events in the History of James W. C. Pennington, Pastor of a Presbyterian Church, New York, Formerly a Slave in the State of Maryland, United States Negro Orators and their Orations, edited by Carter G. Woodson. Lift Every Voice: African American Oratory, 1787-1901, edited by Philip S. Foner and Robert Branham. Early Negro Writing, 1760-1837, edited by Dorothy Porter. Angela Davis, Abolition Democracy: Beyond Prisons, Torture, and Empire. John Henrik Clarke, Critical Lessons in Slavery and the Slave Trade: Essential Studies and Commentaries on Slavery, in General, and the African Slave Trade, in Particular. Elizabeth McHenry, Forgotten Reader: Recovering the Lost History of African American Literary Societies To listen to this episode, please visit our podcast page. In this episode, Olivia Branscum speaks with Nastassja Pugliese, Assistant Professor of Philosophy at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. We talk about the life, work, and reception of the nineteenth-century Brazilian philosopher, Nísia Floresta Brasileira Augusta (born Dionísia Gonçalves Pinto in 1810). Nastassja and I talk about Nísia’s philosophy of education, her enlightenment critique of slavery and colonialism, and the common misconception that Nísia translated the work of Mary Wollstonecraft. Though only one of Nísia’s essays has been translated into English, listeners can find some of her writings in French and Italian, and should keep an eye out for Nastassja’s forthcoming introduction to Nísia with Cambridge University Press. Further Reading Primary Texts By Nísia Floresta: Direitos das mulheres e injustiça dos homens (Women's rights and injustice of men), 1832 Páginas de uma vida obscura (Pages of a dark life), 1855 Opúsculo humanitário (Humanitarian brochure), 1853 A lágrima de um Caeté (The tear of a caeté), 1847 “Woman,” translated by Livia A. de Faria in 1865 By others: Woman not inferior to man, or, A short and modest vindication of the natural right of the fair-sex to a perfect equality of power, dignity, and esteem, with the men, by the anonymous “Sofia/Sophia,” 1739 Woman’s superior excellence over man, or, A reply to the author of a late treatise entitled, Man superior to woman…, by the anonymous “Sofia/Sophia,” 1740 The Woman as Good as the Man: Or, The Equality of Both Sexes, by Poulain de la Barre, trans. A. L., London: N. Brooks., 1677 Secondary Texts Gender, Race and Patriotism in the Works of Nísia Floresta, by Charlotte Hammond Matthews “Overthrowing the Floresta-Wollstonecraft Myth for Latin American Feminism,” by Eileen Hunt Botting and Charlotte Hammond Matthews Nísia Floresta, by Nastassja Pugliese, under contract with Cambridge University Press (2023) [Originally published on Facebook 24 February 2021]

Our last post about Mary Ann Shadd Cary is about a sermon. We know little about this sermon, only that it was delivered to an audience in Chatham, Ontario, in 1858. The more we read it, the more complex it becomes. What is it about? Naturally, there is an abolitionist theme. However, how to understand sentences such as “The spirit of true philanthropy knows no sex” or “She (woman) too is a neighbour”? Here is one of the intro paragraphs. “These two great commandments [to love the Lord our God with heart and soul, and our neighbour as our self], and upon which rest all the Law and the prophets, cannot be narrowed down to suit us but we must go up and conform to them. They proscribe neither nation nor sex – our neighbour may be either the oriental heathen, the degraded Europe and or the enslaved colored American. Neither must we prefer sex the slave-mother as well as the slave-father”. This sermon is about more than just the colour of our skin. To me, it’s about love. Love that is both to “the Lord our God”, to “our neighbour”, and to ourselves too. Love “upon which rest all the Law and the prophets”, and that “cannot be narrowed down to suit us”, but that “we must go up and conform to” it. Further in the sermon, Mary Ann Shadd Cary says that we should “waive all prejudices of education, birth, nation or training” to practice that kind of love. That illustrates that she is not talking about sexual or bodily love; she is talking about transcendental love. A love that goes beyond our attributes such as color or sex, for instance. The word “neighbor” could mean everyone. Someone who has a different religious belief than us (“the oriental heathen”), someone whom we don’t respect (“the degraded Europe”), or someone who has been deprived of what we may take for granted (“the enslaved colored American”). But, if we have to consider everyone as our “neighbours” and we have to love them as we would like to be loved, then what would happen to slavery or to inequality? In the end of her sermon, Mary Ann Shadd Cary says that we’re all equal because we share a “common origin”, and were it not for “the monster slavery, we would have a common destiny here.” The meaning of “here” is open to interpretation, but I think she is not limiting her sermon to Chatham, Ontario, April 6th 1858. That is why we’re still talking about her in 2021. --MM [Originally published on Facebook on 17 February 2021]

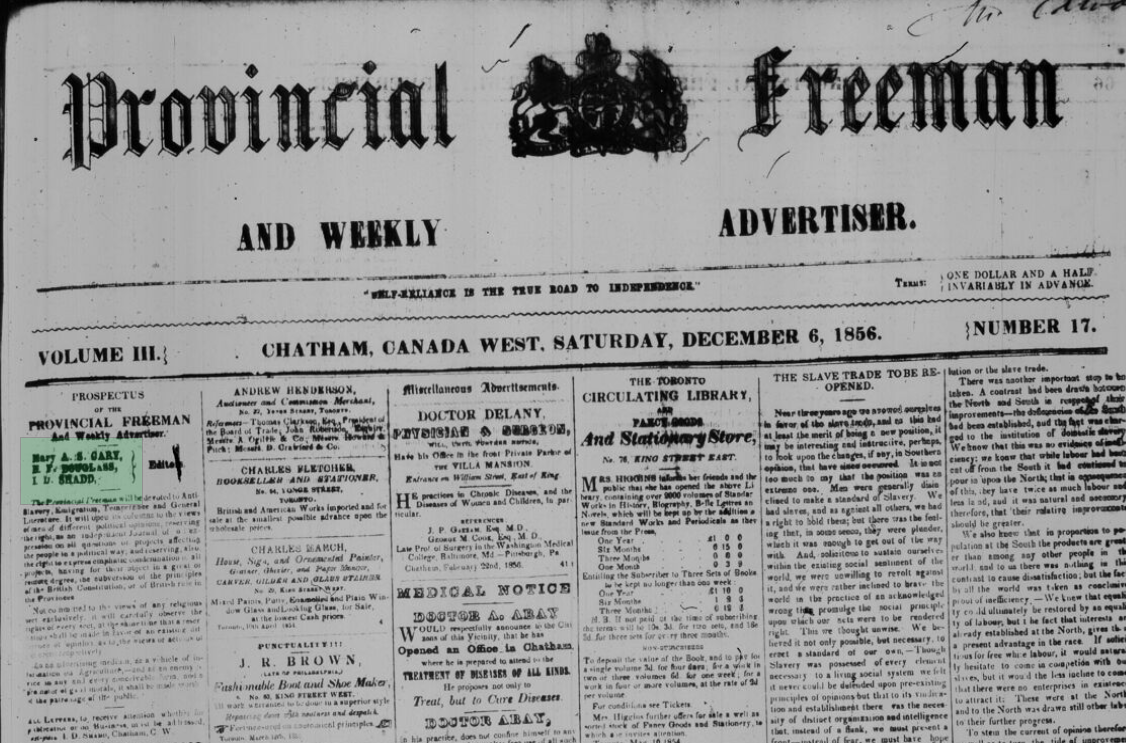

Last week, we talked about Mary Shadd Cary’s A Plea for Emigration. Today, I bring her editorial about the United States presidential election in 1856. Here is a passage: “Instead of a handful of abolitionists, from motives of humanity, the world beholds millions of abolitionists from necessity, and depend upon it there will be hard and bloody work, before the struggle terminate[s]! We heartly deplore the prospect. There is no one so thoroughly depraved! as to love violence for its own sake, but the oppressor of the colored man has forced the necessity” Her words are provocative, aren't they? There will be “hard and bloody” work. Violence will happen whether one protests against slavery or not. The election result shows that slavery is not going to be solved through politics. There is a moral difference among people. It is not a matter of opinion or of facts, it is a matter of moral principles. On one hand, some people believe that slavery is morally acceptable; on the other hand, some do not. Those who do not happen to be oppressed by the former. How to solve that when you do not have rights to protect you and the only people who can recognize those rights into laws are against you? In such scenario, Mary Shadd Cary says that you do not solve this problem without “hard and bloody work”. Violence for its own sake is not morally justifiable, but if all forms of peaceful resolutions are doom to fail, violence as a mean to a greater good may be. It is interesting and cool to see that Philosophy can be found in a newspaper editorial. Next week, we will see that it can be found in a sermon. For historical background: in 1856, James Buchanan was elected the 15th president of the United States. Mary Shadd Cary’s editorial was written two weeks after the election result. She said that “A fearful thing is the result of that last presidential election!”. For her, United States politics was not about being Republican or Democrat; it was about being abolitionist or pro-slavery. Since 1854, the growing apathy towards slaved people, the persecution of abolitionists, and the inefficacy of debates on whether or not slavery was morally acceptable had caused violent riots such as the one known as “Bleeding Kansas”. Mary Shadd Cary’s editorial was predicting that things were going to get worse. Five years after Mr. Buchanan’s election, the United States entered in civil war. --MM Picture retrieved from Canadiana - by Canadian Research Knowledge Network (CRKN) – for research use: [Originally posted to Facebook 11 February 2021]

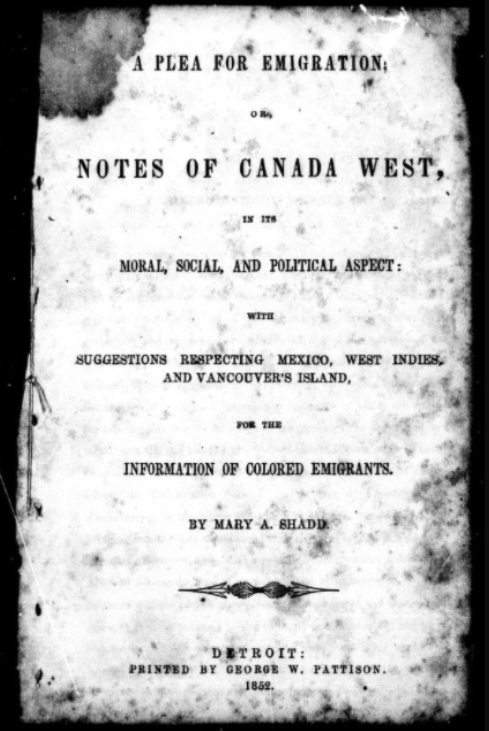

Today I’m going to talk about A Plea for Emigration, the first book published by Mary Shadd Cary. After the Second Fugitive Slave act was passed, life in the United States became even more dangerous. People were looking for a better place to live and Canada was one of those places. Noting the “absence of condensed information accessible to all”, Mary Shadd writes A Plea for Emigration in 1852. As the title suggests, the book not only informs, but pleads. Go to Canada. There the summers are short, people speak mostly French, and there are as many beautiful rivers and streams as apples. However, that seems to be beside the point. There is a passage that I want to highlight. “Lands out of the United States, on this continent, should have no local value, if the questions of personal freedom and political rights were left out of the subject, but as they are paramount, too much may not be said on this point. I mean to be understood, that a description of land in Mexico would probably be as desirable as lands in Canada, if the idea were simply to get lands and settle thereof; but it is important to know if by this investigation we only agitate, and leave the public mind in an unsettled state, or if a permanent nationality is included in the prospects of becoming purchasers and settlers”. The point seems to be that personal freedom and political rights are paramount. But what does she mean by that? To have the possibility to not only buy a land, but also to be a settler. To belong to a community, to have a permanent nationality. Maybe to vote and being a voter, to have rights or titles, to belong in a State. To be respected, protected and allowed to pursue a life with dignity. It is not just about whether the land itself is fertile or not. If it were, there would be no difference between Canada, Mexico or the United States. All lands could be fertile, but not all lands are equal. Picture retrieved from Internet Archive for research use only: https://archive.org/details/cihm_47542/page/n5/mode/2up -MM [Originally published on FB February 3, 2021.]

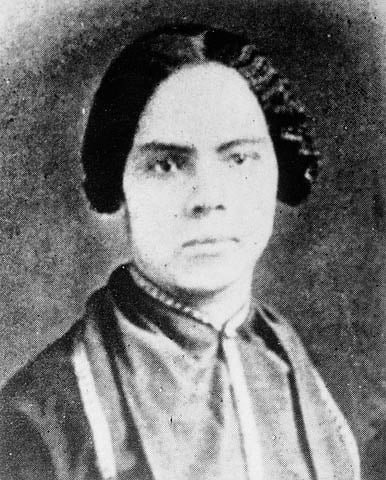

Mary Ann Shadd Cary, an educator, publisher, lawyer and abolitionist, is our woman philosopher of February. In this post, I share some background details about her life. In future posts, I’ll highlight some of her ideas. Mary Ann Shadd was born on October 9th, 1823, to free parents in Wilmington, Delaware, which was a slave state at that time. Her parents belonged to the network known as “The Underground Railroad”. In 1833, Mary Shadd moved with her family to Pennsylvania, which was a free state. There, she went to school, and was educated by Quakers. She became a teacher and taught throughout the northeastern United States. In 1850, the second Fugitive Slave Act was passed by the Congress, making the work of any abolitionist harder and more dangerous. The Act allowed any slave owner to re-enslave an escaped slave whenever they were - even in a state that had abolished slavery It also allowed the punishment of anyone who were helping slaves to escape. In 1851, Mary Shadd moved to Ontario, Canada, and in that same year she met Thomas J. Cary, whom she married and with whom she had two children. She attended the first North American Convention of Coloured Freemen at St. Lawrence Hall, where she met abolitionists Henry and Mary Bibb, publishers of the anti-slavery newspaper Voice of the Fugitive. She founded an affordable school for both white and black students, where she could educate and care for those coming from the US. The school was financially assisted by the American Missionary Association, and we have some letters between Mary Shadd and George Whipple, secretary of the Association (November 27th, 1851), in which Mary Shadd corrects his impression that the school was promoting segregation. In 1852, she published A Plea for Emigration (or Notes of Canada West), which aimed to promote Canada as a destination. She also engaged in a public debate with Henry and Mary Bibb, who defended schools for black students only. Again, Mary Shadd was against segregation. Due to the repercussions of the debate, the American Missionary Association withdrew its funding, leaving Mary Shadd without financial support. So, on March 24th, 1853, Mary Shadd began publishing The Provincial Freeman, her own newspaper. She is considered the first Black woman in North America to publish a newspaper, and one of the first female journalists in Canada. It is said that her newspaper motto was “Self-reliance is the true road to independence”. The Provincial Freeman became a space to promote anti-slavery ideas and women’s rights. We still have access to many of its editorials. To name a few: Anti-Slavery Relations (March 25th, 1854), where Mary Shadd argues for a unity in the anti-slavery movement as a whole; The Presidential Election in the United States (December 6th, 1856), in which she foresaw the beginning of the American Civil War from the victory of candidate James Buchanan. The newspaper closed due to financial pressure in 1860. In 1861, Mary Shadd left Canada to help recruit soldiers for the Union Army in the American Civil War. Years after the war, she enrolled in the first class of Howard University Law School, in Washington, DC, and in 1883, she graduated, becoming the first Black woman to complete a law degree in North America. Also, she wrote for the local newspaper The New National Era, gave public speeches, founded the Colored Women’s Progressive Association (we have the minutes of the first meeting and the statement of purpose), and became a member of the National Woman Suffrage Association. She advocated for the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments at a House Judiciary Committee Hearing. Despite defending those amendments, Mary Shadd criticized the definition of citizen, for it did not give the right to vote to women. Her speech to the House Judiciary Committee was made in January, 1872. She died on June 5th, 1893 of a stomach cancer. In 1994, the Government of Canada recognized Mary Shadd Cary’s leadership, naming her a Person of National Historic Significance. MM (Picture retrieved from: https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/.../Collec.../Pages/record.aspx...) |

Authors

Jacinta Shrimpton is a PhD student in Philosophy at the University of Sydney. She is co-producer of the ENN New Voices podcast Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed