|

[Originally posted on Facebook March 24, 2021.]

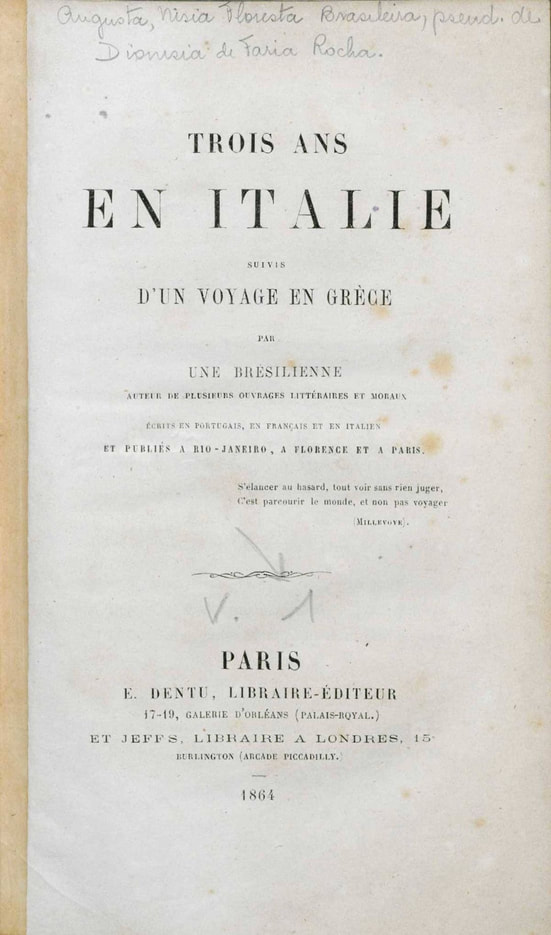

Our fourth post on Nísia Floresta is from “Trois ans en Italie: suivis d’un voyage en Gréce” (Three years in Italy followed by a trip to Greece). This book was published in 1864 in France, but only was translated into Portuguese in 1998. The book is not only a journal of her trips throughout Italy and Greece, full of descriptions of the landscapes and architecture; it is an analysis of the history and political development of those nations. In it, Nísia foresees the Italian Unification [1]. Here is an interesting passage: “If such rebellions [2] were never to be excusable, (…) could the same be said about the savage representatives of noble races (the black enslaved), whom are tortured with humiliating punishments? Furthermore, if war, this infernal scourge whose existence must be banned among all civilized people, can be somehow excused, then it must be done to free our land against the tyrant invaders whom claimed themselves sovereigns. Italy has been tormented, not for days, months, or years, but for centuries, by the despotic yoke of all kinds of conquerors. Its war, therefore, is excusable and even just (…) Italy has risen because its brave sons escaped from the heavy prisons in which they were chained by their tyrants. The spoiled motherland, looking at its noble sons, divided and enslaved by the ambitious despotism of foreign usurpers, finally regained freedom and, likewise, its rights” (pp.317-318). This is a subtle passage. If the Italian rebellions are not excusable for fighting against oppression and for the right to be free, then the same could be said to any rebellion by “the savage representatives of noble races”. But we do consider the Italian rebellions excusable. So, we must consider as excusable any rebellion made by the “noble races”. And by “noble races” Nísia means the black enslaved. It is a powerful analogy and it is logically valid (it is a Modus Tollens). She goes on to state the reasons of the Italian rebellions, leaving us to continue her analogy. Their rebellions are excusable because they fight against “tyrant invaders whom claimed themselves sovereigns”. This is a just cause for Nísia. The Italians were enslaved by “ambitious despotism of foreign usurpers” and they just seek freedom and rights. Is not that what happened in Africa with the African people? Since both Italians and Africans share the same burden of slavery by foreigners and the claim for freedom, to advocate for the Italian unification would be to advocate against slavery. Here, “slavery” is meant in the broad sense: of one nation over another. Thus, it does not reference the color, the language, or the culture of the nation. If one nation is oppressing, enslaving another, it is not right. Thus, any rebellion that claims freedom and rights is excusable and justified. In one single passage, Nísia praises the Italian unification and defends abolitionism. ----- Retrieved from: https://memoria.ifrn.edu.br/.../Tr%c3%aas%20anos%20na... Original in French: 1st Volume: http://objdigital.bn.br/.../drg291826/drg291826.html... 2nd Volume: http://objdigital.bn.br/.../drg1414580/drg1414580.html... [1] Also known as “Risorgimento” (Resurgence), the Italian Unification was the historical process which unified Italian kingdoms into one, resulting the Kingdom of Italy in March 17th, 1861. It was a consequence of the ideas of French revolution that were brought by Napoleon’s troop to Italy when he was at war with Austria. Here is a good article of Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/place/Italy/Unification [2] Here Nísia is referring to the many rebellions that were emerging in Italy prior to its unification. She explains them in previous pages. Although King Francisco II defeated Garibaldi’s troops in Naples, Garibaldi himself won battles against General Landi in Sicily, such as the battle of Calatafimi, and in Munrriali. * Se a revolta jamais fosse desculpável, (...) o mesmo poderia se afirmar em relação a selvagens representantes de raças nobres (escravos negros), a quem se tortura com degradantes castigos? Além disso, se a guerra, flagelo infernal cuja existência deve ser banida dentre todos os povos civilizados, pode ser de alguma forma desculpada, é preciso ser feita para livrar a nossa terra dos tiranos invasores que se fizeram soberanos. A Itália gemeu, não por dias, meses ou anos, mas durante séculos, sob o jugo despótico de todo tipo de dominadores. Sua guerra, pois, é desculpável e até mesmo justa, (...) A Itália ressurgiu em virtude de seus bravos filhos terem escapado das pesadas cadeias com que foram acorrentados por seus tiranos. A espoliada mãe pátria, olhando para seus nobres filhos secularmente divididos e escravizados pelo despotismo ambicioso de usurpadores estrangeiros, recobrou finalmente a liberdade e, da mesma forma, seus direitos. (pp.317-318) Translated by Matheus Iglessias Mazzochi -MM

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Authors

Jacinta Shrimpton is a PhD student in Philosophy at the University of Sydney. She is co-producer of the ENN New Voices podcast Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed