|

In this episode, Haley Brennan talks with Kathryn Sophia Belle, Associate Professor of Philosophy at Penn State University and founder of the Collegium of Black Women Philosophers, about Black Feminist critiques of Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex. We talk about her upcoming book on the topic, with chapters on Claudia Jones, Lorraine Hansberry, Maria Stewart, Anna Julia Cooper, and Audre Lorde among others. We also talk about the philosophical-historical origins of the concept of intersectionality and the triple oppression thesis, what it looks like to offer alternative accounts to Beauvoir’s, and creating the spaces and projects that you need in academic philosophy.

Bibliography Kathryn Sophia Belle, “Interlocking, Intersecting, and Intermeshing: Critical Engagements with Black and Latina Feminist Paradigms of Identity and Oppression” in Critical Philosophy of Race, Vol. 8, Nos 1-2, 2020, pages 165-198. Kathryn Sophia Belle, “Maria Stewart (August 20, 1829 – August 19, 1834)” in 400 Souls: A Community History of African America, 1619-2019, edited by Ibram X. Kendi and Keisha N. Blain (Random House). Kathryn Sophia Belle, “Being a Black Woman Philosopher: Reflections on Founding the Collegium of Black Women Philosophers” in Hypatia, Volume 26, Issue 2, Spring 2011, pages 429-437. Claudia Jones, “An End to the Neglect of the Problems of Negro Women” (1949). Anna Julia Cooper, A Voice from the South (1892). bell hooks, “True Philosophers: Beauvoir and bell”, in Beauvoir and Western Thought from Plato to Butler, edited by Shannon M. Mussett and William S. Wilkerson (2012). Words of Fire: An Anthology of African-American Feminist Thought, edited by Beverly Guy-Sheftal (1995). Octavia Butler, Parable of the Sower. Grand Central Publishing: 1993. Octavia Butler, Parable of the Talents. Grand Central Publishing: 1998. Elizabeth Spelman, Inessential Woman: Problems of Exclusion in Feminist Thought (1988). Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex (1949). Audre Lorde, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House.” 1984. Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Ed. Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press. 110- 114. 2007

0 Comments

In this episode, Olivia Branscum speaks with Nic Bommarito, Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Simon Fraser University. We discuss the French philosopher Simone Weil (1909-1943), focusing especially on what she has to teach us about the moral value of attention and the true uses of education. Nic and I also talk about his work in Tibetan Buddhist thought and his experiences studying figures and traditions that have been excluded from mainstream histories of philosophy.

Further Reading Primary Texts (by Simone Weil) “Reflections on the Right Use of School Studies with a View to the Love of God” (written c. 1942, published in Waiting for God) La Pesanteur et la Grâce (available in English translation as Gravity and Grace) (1947) L'enracinement : Prélude à une déclaration des devoirs envers l'être humain (available in English translation as The Need for Roots) (1949) Attente de Dieu (available in English Translation as Waiting for God) (1950) Secondary Texts “Private Solidarity” by Nicolas Bommarito (2015) nner Virtue by Nicolas Bommarito (Oxford University Press, 2018) Seeing Clearly: A Buddhist Guide to Life by Nicolas Bommarito (Oxford University Press, 2020) To listen to this episode, please visit our podcast page.

I was immediately drawn to Veronica Franco after learning she was not only a feminist and poet, but also a sexworker. Franco’s writing is proudly erotic and boldly explicit as she describes her life as a courtesan. To me, Franco’s unapologetic confidence in her sexuality exemplifies an aspect of womanhood that even today sometimes feels taboo.

Moderata Fonte’s writing, on the other hand, felt more familiar to me. Fonte presents her philosophy through a dialogue held between women. Although familiar in style, Fonte is exceptional in her character development. While reading, I could feel the camaraderie between the women as they joked about things like the inevitable imprisonment of marriage with a soon-to-be bride. I was moved by the sense of community these women provided each other with (although this serves only as the backdrop to Fonte’s excellent feminism and natural philosophy). While many philosophers appeal to the dialogue form, few create such impressive and dynamic characters who can put forth important ideas in a way that does not feel forced or stiff. Perhaps in a manner less graceful than her predecessors, Lucrezia Marinella also presents strong feminist arguments. Aside from her philosophy, Marinella’s descriptions of men like Aristotle are simply fun to read. Zeroing in on the defects of his work many times throughout her text, Marinella describes Aristotle as “foolish…cruel…a fearful, tyrannical man, and sarcastically, as “our good friend Aristotle.” Marinella is ruthless in her analysis of the works of men like Aristotle, making her overall text a page-turner (an accomplishment which sometimes feels like a rarity in philosophical writing). Unknowingly saving the best for last, I finished my research with Arcangela Tarabotti. In Paternal Tyranny, Tarabotti is explicit in her call for an end to the practice of men forcing women who do not have religious vocations into convents. Tarabotti directs her work at men, bringing them into the dialogue by continuously addressing “you”. Without hesitation, Tarabotti puts these men on trial: “Your lying insulting tongues never cease… You cruel hypocrites… You bloodthirsty butchers… You liars!” Throughout her work, Tarabotti’s anger and hurt is palpable. By the end of the text, I could feel the desperation in her voice as she begged for the most basic form of empathy from the most apathetic oppressors. On a personal note, there is something deeply familiar about Tarabotti’s anger. To me, she seemed most frustrated by the hypocrisy of men who call themselves Christians but fail to uphold Christian values. Of course, this kind of experience of religious groups is not isolated to Tarabotti or 17th century Venice. And so, her frustration seems timeless, and, in many ways, she took the words right out of my mouth. Overall, in reading the texts of these women, I enjoyed engaging with various styles of rhetoric, all of which are strong in personality and conviction. Their work serves as a reminder of the importance of the presence of the perspective and ideas of the oppressed in philosophical discussions. In Paternal Tyranny, “Book Two,” Tarabotti argues against the belief that women are to blame for adultery. She describes this view writing,

"With artful casuistry, you spread it around that adultery is more justly condemned and punished in the wife than the husband on three counts: the damage done to the husband’s honor; the possibility of inheritance by illegitimate sons; and the threat to the safety of the husband’s life (since the adulterer supposedly kills her husband to protect his own life and allow himself greater freedom to sin). But these are not reasons; they are the ravings of evil, unbridled thoughts to allow yourself greater freedom to commit crimes without fear of reproof." (110) Tarabotti carefully responds to each claim outlined above. She begins by arguing against men who claim that women endanger the honor of their husbands when they commit adultery. Tarabotti uses the sexist reasoning of men which says that only they can bestow honor onto another to show that women, in turn, cannot hurt the honor of their husbands through adultery. She writes, “First you claim that a woman of base lineage who marries into a noble family cannot lower her husband’s status, just as a noble lady cannot raise the status of a commoner whom she marries” (111). Tarabotti argues that if a woman does not hold the power to raise or diminish the status of her husband in marriage, then, even if she commits adultery, she still cannot affect her husband’s honor. She concludes, “a woman’s dishonorable conduct… cannot bring dishonor to a house, but rather it is the man’s defects, the same man who boasts of dispensing honors to others” (111). Here, Tarabotti appeals to men’s “own weapons,” or reasoning, to defend women against unjust charges in adultery (111). Tarabotti then responds to the second claim: that women are to blame for illegitimate children and the loss of rightful inheritance. Tarabotti stresses that men are also to blame for their participation in adulterous acts. Addressing men, she writes, “for without your participation and your intrigues, illegitimate children would not be born, whose inheritances you usurp” (112). Tarabotti reframes the problem of illegitimate children as a result of men seducing women to usurp the legacy of rightful heirs. She quickly responds to the third claim, that adulterous women endanger the lives of their husbands, by referencing the story of King David and Bathsheba. In the biblical story, King David impregnates Bathsheba who is married to Uriah. Tarabotti asks her reader to “remember that it was… King David who, unknown to Bathsheba, had her husband Uriah killed” (112). She argues that King David was the direct cause of Uriah’s death, not Bathsheba who was unaware of King David’s actions. Again, Tarabotti calls her audience to recognize that women do not act alone in adultery. Finally, Tarabotti claims that the “double sexual standard” held against women in adulterous affairs opposes teachings of the Catholic church (113). She argues that “throughout the Scriptures, male and female are on equal footing when it comes to marital legislation” (113). Tarabotti references Saint Paul as an advocate of women and her views. She writes, “listen to Saint Paul agreeing with me on the reciprocal obligations between husband and wife: ‘If any brother hath a wife that believeth not, and she consent to dwell with him, let him not put her away. And if a [believing wife] hath a husband that believeth not, and he consent to dwell with her, let her not put away her husband’ (1 Cor 7:12-13)” (113). Tarabotti argues that by using the adjective “believing” to describe the wife and not the husband, Saint Paul “appreciates women’s naturally Catholic soul and sides with it” (113). Tarabotti uses Saint Paul to argue that, as seen in Catholicism, men and women should be held to the same standards in marriage. Tarabotti underlines the shared participation between men and women in adulterous acts and argues that blaming only women opposes Catholic teaching and contradicts other misogynist views held by men. Within this argument, Tarabotti showcases her ability to reconstruct opposing arguments and tactfully respond to each claim while utilizing important texts and impressive reasoning. --MP Source info: Paternal Tyranny. Edited and translated by Letizia Panizza. The University of Chicago Press, 2004. Image info: The Woman Taken in Adultery. Guercino. Italy, 1621. Source: https://artvee.com/dl/the-woman-taken-in-adultery-2/ In “Book Two” of Paternal Tyranny, Tarabotti argues that women should receive an education equal to that of men. She writes: "Do not scorn the quality of women’s intelligence, you malignant and evil-tongued men! Shut up in their rooms, denied access to books and teachers of any learning whatsoever, or any other grounding in letters, they cannot help being inept in making speeches and foolish in giving advice. Yours is the blame, for in your envy you deprive them of the means to acquire knowledge. As Socrates said in Plato’s Symposium, women do not lack intellect or a natural disposition to succeed in every understanding and every kind of learning equally to men." (99) In advocating for equal education, Tarabotti first establishes that intelligence is not an intrinsic quality. She argues that all learned men became intelligent only through receiving an education: “All philosophers and men of learning have gained their knowledge by studying; nobody was ever born with infused wisdom” (97). She references Plato’s Symposium to argue further that both men and women share a similar disposition to learn. In asserting that women share this disposition to learn with men, Tarabotti refutes the argument that women are naturally less intelligent than men and as a result, less worthy of an education. She argues that women do not “lack intellect or a natural disposition to succeed in every understanding and every kind of learning equally to men” (99). Instead, women lack access to the kind of education that make men intelligent. Tarabotti highlights the way men inhibit women from receiving a proper education. She describes the hypocrisy of men who “while reproaching women for stupidity…strive with all [their] power to bring them up and educate them as if they were witless and insensitive” (99). Tarabotti criticizes men who treat women as if they were naturally less intelligent and use this prejudice as reason for providing women with inadequate education or no education at all: “[Men] give [women] as a governess another woman, also unlettered, who can barely instruct them in the rudiments of readings, to say nothing of anything to do with philosophy, law, and theology. In short, they learn nothing but the ABC, and even this is poorly taught” (99). Tarabotti argues that even when a woman does receive an education, she receives her instruction from another uneducated woman. This cycle ensures that all women remain less intelligent than men. Thus, Tarabotti reframes the issue of women’s observed lesser intelligence as stemming from a man-made system and not from the nature of women themselves.

Throughout “Book Two,” Tarabotti establishes intelligence as an attribute only available to those who receive proper education and exposes men for creating a system of inadequate education for women so that they may maintain their power. --MP Source info: Paternal Tyranny. Edited and translated by Letizia Panizza. The University of Chicago Press, 2004. Image info: Standing Woman Holding a Scroll. Artist unknown. Italy, 16th century. Source: https://artvee.com/dl/standing-woman-holding-a-scroll Throughout Paternal Tyranny, Tarabotti argues that when men force women into nunneries, they act contrary to God’s will and strip women of their deserved freedom. She argues first that, as seen in Adam and Eve’s creation, God made men and women equal in value and in their possession of a free will. She writes,

"If woman had been deprived of freedom’s bounty, God would not have given her to man, since she is “A help like unto himself” (adiutorium simile sibi) (Gn 2:18). God furthermore did not give woman to man as a help inferior to himself; woman’s creation was one of parity…both were made similar in knowledge and with equal claims to eternal glory. As soon as His Majesty said the word “help,” He immediately added, “like unto himself,” implying that woman is of just as much value as man." (50) Tarabotti utilizes the creation narrative to defend God’s intent in the making of women. She challenges a reading of the creation story where Eve is inferior to Adam because she was made as a “help” to man. Tarabotti argues that the language found in Genesis during this moment of creation reveals the true and equal value of women. According to Tarabotti, the creation of men and women “was one of parity” where both parties were made equal in “knowledge and with equal claims to eternal glory.” Most importantly, God also made “the human will… free and autonomous for all” (127). Men who make “use of holy pretexts,” such as the creation story, to defend their oppression of women, then, “have no regard for God’s will in any manner” (127). Likewise, when men force women to live in convents, they defy God and “dare to endanger free will” (43). Tarabotti argues that in this state of imprisonment, women “possess no less than [men] all the advantages of free choice, which can be taken away only by death; yet [men] still condemn them to a living hell” (81). Despite always possessing their God-given free will, women forced into convents cannot act freely: they are “restrict[ed]… to one place” and must uphold “cruel obligations” and religious vows (81). As a result, these women live only as “imprisoned bod[ies]” (54). Tarabotti compares the men who oppress women in this way to “Satan” because they “crave greater glory than God’s by taking away free will from women” (54). In taking away the freedom of women, men reject God’s will which calls for both sexes to live freely and impose their own wills onto the world instead. In doing so, men also push women further away from God. Instead of growing in their love for God while in the convents, women “blame God who permits but does not agree with their fates” (129). Men who force women into convents “dispose of their wills” and cause them to lose faith (81). In stripping women of their freedom, Tarabotti concludes, men defy God who intended free will to be enjoyed by both men and women. --MP Source info: Paternal Tyranny. Edited and translated by Letizia Panizza. The University of Chicago Press, 2004. Image info: Creation of Eve. Painted by Michelangelo. Cappella Sistina, Vatican, 1509-10. Source: https://www.wga.hu/html/m/michelan/3sistina/1genesis/5eve/05_3ce5.html Arcangela Tarabotti was born in 1604 in Castello, a neighborhood of Venice, to Maria Cadena and Stefano Tarabotti. She had four sisters and two brothers. Like her father, Tarabotti was born lame. Her condition made her unsuitable for marriage in her father’s eyes and at the age of eleven, she was sent to the Benedictine Convent of Sant’Anna. At sixteen, Tarabotti took her first vows of poverty, chastity, obedience, and stability. She took her final vows in 1623. Tarabotti describes herself as an autodidact and criticizes the inadequate education available to her during her time in the convent. Despite never receiving a sufficient education, Tarabotti produced seven works, five of which were published during her lifetime. Tarabotti died in 1652 at the age of forty-eight in Sant'Anna.

Tarabotti’s earliest works, the Inferno Monacale and the Tirannia Paterna, address forced monachization: the practice of placing women, who do not have religious callings, into convents. In these works, Tarabotti critiques parents who use convents to rid themselves of their unmarried daughters. Despite her best efforts, including sending copies to France, neither of these provocative texts were published in Tarabotti’s lifetime. Her first published text, Paradiso Monacale (1643), recognizes the benefit of nunneries for young women with genuine religious vocations. This more conventional work established Tarabotti as a writer and expanded her literary circle throughout Venice. Tarabotti’s Lettere Familiari e di Complimento (1650), showcases her strong relationships with various important men and women throughout Italy and France such as Ambassador Henri Bretel de Grémonville, Vittoria della Rovere of Florence, Cardinal Mazarin of France, and members of the Incogniti in Venice. Still, Tarabotti faced public scrutiny for her bold critiques of the Venetian patriarchy and her responses to various anti-women texts. In the next few weeks, I will be looking at passages from one of her first works, Tirannia Paterna, published posthumously in 1654. I will explore Tarabotti’s critiques of the Venetian patriarchy, her appeal to figures like Dante, and her explication of the biblical grounding for the excellence of women as she highlights the abuse parents subject their daughters to when they force them into prison-like convents. --MP Image Info: A Nun Saint. Simone Pignoni. Italy, 1611-1698. Source: https://artvee.com/dl/a-nun-saint/ Despite her many critiques of Aristotle, Marinella utilizes Aristotle’s concept of material and efficient causes in her defense of women. She writes,

Marinella argues that each creature shares an efficient cause in the one “Eternal Maker” or God. Despite sharing this “productive cause,” however, the creatures of the world vary in degree of perfection. Marinella claims that the degree of a creature’s perfection mirrors the perfection of the Idea or Form of that creature. Here, again, Marinella appeals to the Platonist Forms. She quotes Petrarch, who, while speaking about his beloved, Laura, writes, “In what part of the world, in what Ideas was the pattern from which nature copied that lovely face, in which she has shown down here all that she is capable of doing up there?” (54) Marinella uses Petrarch, a fellow Platonist, to highlight how the beauty and perfection of women can be traced back to the “pattern” or Idea of women in God.

Marinella describes God’s “divine precognition” of Ideas writing, “To give you a clearer example of this sort of Idea, let us pretend that an artist wishes to paint a beautiful Venus… There is no doubt that before the artist begins to draw or paint he will have fixed in his mind the sort of figure he wishes to paint and only then will he proceed to bring this image to life” (53). Like the painter, God imagines the Idea of each creature before He creates them. God also determines the degree of perfection for these creatures as He “decides which things are of less value and which are worthier”. According to Marinella, God’s “Idea of women is nobler than that of men” as seen in their unmatched “beauty and goodness” (53). In making women more perfect in Form, then, God reveals that women are worthier creatures than men. Marinella swiftly argues at the end of the chapter that women are also more excellent than men in their material cause. She writes, “I do not need to make an effort over this since, as woman was made from man’s rib, and man was made from mud or mire, she will certainly prove more excellent than man, as a rib is undoubtedly nobler than mud” (54). Marinella positions her argument within the context of the story of creation. As Eve is made from Adam’s rib and Adam made from mud, Eve, who represents all women, has a superior material cause in comparison to Adam, who represents all men. Here, once again, Marinella carefully works Aristotle’s philosophy into her defense of women as she concludes that, in both their material and efficient causes, women are superior to men. In doing so, Marinella shows her ability to critique thinkers like Aristotle while appreciating, understanding, and employing other aspects of their philosophy within a feminist defense. --MP Text source: The Nobility and Excellence of Women, and the Defects and Vices of Men. Edited and translated by Anne Dunhill, The University of Chicago Press, 1999. Image info: The Virgin Reading. Painted by Vittorio Carpaccio. Published in Venice, 1505-1510. Source: https://www.wga.hu/frames-e.html?/html/c/carpacci/2/08virgin.html  It is hard to ignore the amusing and explicit contempt employed by Marinella in her prose as she criticizes various male thinkers. Throughout The Nobility and Excellence of Women and the Defects and Vices of Men, Marinella often critiques Aristotle and his claim that women are, by nature, the inferior sex. In rebutting Aristotle, Marinella defends her natural philosophy and advocates for equal opportunity among the sexes. She writes, "But in our times there are few women who apply themselves to study or the military arts, since men, fearing to lose their authority and become women’s servants, often forbid them even to learn to read or write. Our good friend Aristotle states that women must obey men everywhere and in everything and not such for anything that takes them outside their houses. A foolish opinion and cruel, pedantic sentence from a fearful, tyrannical man. But we must excuse him, because, being a man, it is only natural he should desire the greatness and superiority of men and not of women. Plato, however, who was truly great and just, was far from imposing a forced and violent authority. He both desired and ordered women to practice the military arts, ride, wrestle and in short, to instruct themselves in the needs of the Republic… If [women] do not show their skills, it is because men do not allow them to practice them, since they are driven by obstinate ignorance, which persuades them that women are not capable of learning the things they do." (79-80) Marinella argues that, in order to maintain their authority, men do not allow women to receive an education or to practice the military arts. Out of fear, these men repress those, mainly women, who hold the potential to threaten their power. For Marinella, Aristotle serves as a prominent example of this “tyrannical man.” Marinella pits Aristotle against Plato “who was truly great and just.” Unlike Aristotle, according to Marinella, Plato rightly advocates for the training of women in various practices dominated by men such as riding, wrestling, and military arts. Any absence of skill or ability found among women in these fields results only from the lack of education and opportunities available to women. Marinella describes the circular nature of this phenomena as a self-fulfilling prophecy where men keep women from being educated and then become convinced that women cannot learn. According to Marinella, Aristotle’s endorsement of limiting women to household work and excluding them from schooling exposes the ignorance and injustices in his philosophy. Marinella also argues that Aristotle’s natural philosophy, which he uses to defend his anti-women views, fails upon further consideration. Both Marinella and Aristotle hold that a person’s bodily temperature says something about their character or nature. According to Marinella, however, Aristotle argues that men are hotter than women and therefore, more noble. She writes, “The good Aristotle, state[s] that women are less hot than men and therefore more imperfect and less noble. Oh what irrefutable and powerful reasoning! I now believe that Aristotle did not consider the workings of heat with a mature mind, nor what it signifies to be more or less hot, nor what good and bad effects derive from this” (130). Unlike Aristotle, Marinella argues that only moderate heat reflects a noble soul. “Excessive heat,” like that of men, “makes souls precipitous and unbridled” while “little and failing heat…is powerless for the soul’s operations” (130). Marinella declares that “women are cooler than men and thus nobler, and that if a man performs excellent deeds it is because his nature is similar to a woman’s, possessing temperate but not excessive heat” (131). As a defense of women as the superior sex, Marinella argues that Aristotle misunderstands the relationship between temperature and soul as the excessive heat of an individual exposes only the defects of their soul. If men are hotter than women as, according to Marinella, Aristotle believes they are, then they are inferior to women by nature. Not only does Marinella attack Aristotle’s misogyny in advocating for inequal opportunity among the sexes, she also highlights the failures of his natural philosophy in his attacks on the nature and temperature of women. Although decorated with colorful insults and bold sarcasm, Marinella’s arguments against Aristotle clearly reveal her expansive knowledge of thinkers like Plato and her own extensive natural philosophy. -MP Text source: The Nobility and Excellence of Women, and the Defects and Vices of Men. Edited and translated by Anne Dunhill, The University of Chicago Press, 1999.

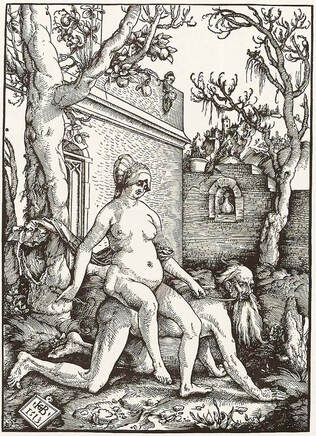

First image info: Image taken from Maria Bandini Buti, Enciclopedia biografica e bibliografica italiana: poetesse e scrittrici (Roma, 1942), vol. 2, p. 10. Source: https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/efts/IWW/Portraits/HTML/A0190.html Second image info: Aristotle and his lover Phyllis. Hans Baldung Grien, 1515. http://www.ibiblio.org/wm/paint/auth/baldung/ In reading chapter III of The Nobility and Excellence of Women and the Defects and Vices of Men, I am most interested in Marinella’s appeal to the philosophies of Aristotle and Plato in establishing her bold feminism. Marinella argues that the natural beauty of women reveals the divine excellence of their souls. She writes:  So if women are more beautiful than men, who, as can be seen, are generally coarse and ill-formed, who can deny that they are more remarkable? Nobody, in my opinion. Thus it can be said that beauty in a woman is a marvelous spectacle and a miracle worthy of respect, though it is never fully honored and respected by men. But I wish to go further and show that men are obliged and forced to love women, and that women are not obliged to love them back, except merely from courtesy. I also wish to demonstrate that the beauty of women is the way by which men, who are moderate creatures, are able to raise themselves to the knowledge and contemplation of the divine essence. (62) Marinella first argues that women’s being naturally more beautiful than men reveals the superiority of their souls. She writes, “The greater nobility and worthiness of a woman’s body is shown by its delicacy, its complexion, and its temperate nature, as well as by its beauty, which is a grace or splendor proceeding from the soul as well as from the body” (57). In order to argue that one’s bodily appearance mirrors the state of one’s soul, Marinella appeals to the idea of the hylomorphism found in Aristotle where the soul is the form of the body and body is the matter of the soul. She asks, “What is the form of the body if not the soul? The greatest poets teach us clearly that the soul shines out of the body as the rays of sun shine through transparent glass” (57). The soul, acting as the form of the body, serves as a template for the appearance of the body and, in its bodily existence, reveals the true nature of the being. The more beautiful a woman’s body is, then, according to Marinella, the more beautiful her soul will be. In comparison to women, however, “all men are ugly” and therefore, inferior in their souls (63). With Platonism in mind, Marinella argues that the origin and cause of the external beauty of women is God. God uses the forms, such as beauty, to fashion the external world in the most perfect way. Marinella describes God as “the minister who takes [beauty] … from every other source of perfection and excellence” in order “to create this rich and esteemed treasure house of beauty” (62). Corporeal beauty, then, is personally bestowed by God onto only the worthy creatures of the world (59). Great beauty, like that seen in the bodies of women, reveals a divine nobility and excellence in the being. She writes, “Each writer, Platonist, and poet affirms that beauty comes from God… Divine beauty is, therefore, the first and principal cause of women’s beauty, after which come the stars, heavens, nature, love, and the elements” (60). Like other beauties in the external world, the beauty of women stems from God. Men, however, do not have this beauty. This disparity, according to Marinella, shows that men are less worthy beings than women who are chosen to embody a divine form such as beauty. Most interestingly, Marinella concludes that if women are more beautiful than men, and if this beauty originates in God, then men are obligated to love and contemplate the beauty of women because it will lead them to knowledge of God. She asks, “What poet is there, however coarse, who does not state openly that beauty is the path that guides us directly to the contemplation of divine wisdom…beauty, not being earthly but divine and celestial, always raises us toward God, from whom it is derived” (66). Marinella’s argument here positions women as invaluable gateways to God and beauty itself. In this way, women, by their very nature, demand worship and love while men do not. Nodding to Homer, Marinella describes this phenomena as a “golden chain” (66). Similar to Diotima’s Ladder of Love, found in Plato’s Symposium, Marinella describes our love for physical beauty as a way of ascension to higher forms of beauty. First, we see “corporeal beauty” which is “gazed at and considered by the mind, through the means of the outer eye” (66). In admiration of this beauty, we “ascend” and look “with the internal eye at the soul that, adorned with celestial excellence, gives form to the beautiful body” (66). In contemplation of the soul, we consider the “angelic spirits” and “this contemplative mind seats itself within great light… of the one who supports the chain” (66). In appreciating corporeal beauty, we are led to “delight in Him” and are “made happy and blessed” (66). Men, then are obligated to contemplate the beauty of women because they will be naturally led to a contemplation of the divine. Marinella defends the superiority of women with an appeal to Aristotle’s hylomorphism, Plato’s forms, and by arguing that their bodily beauty reflects their beautiful souls which lead men to knowledge of God. --MP Text source: The Nobility and Excellence of Women, and the Defects and Vices of Men. Edited and translated by Anne Dunhill, The University of Chicago Press, 1999.

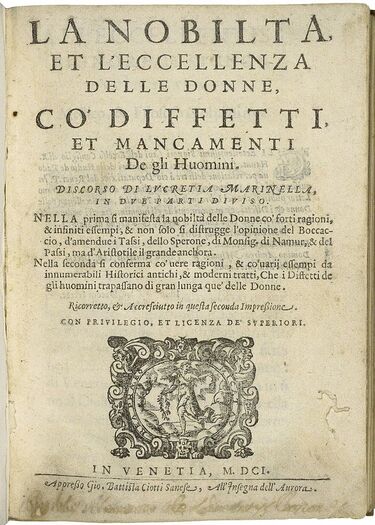

Image info: The title page of Lucrezia Marinella's La nobilita, et l’eccellenza delle donne. Published in Venice 1601. Source: http://luna.folger.edu/luna/servlet/s/184k1c |

Authors

Jacinta Shrimpton is a PhD student in Philosophy at the University of Sydney. She is co-producer of the ENN New Voices podcast Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed